The poetic conversation between Vāsiṣṭha-gaṇapati-muni and Ambikā-datta that took place at the conference of scholars—‘paṇḍita-goṣṭhi’—at Nava-dvīpa (Nadia) is a good example for the genre of dialogue-poetry.

Vāsiṣṭha-gaṇapati, who was then a young lad of twenty-two, went to participate in the extempore poetry—‘āśukavitā’—competition in Nava-dvīpa, following the advice of Śivakumāra, the great scholar of Kāśi. There, Gaṇapati was trying to find out from the person sitting next to him about Ambikā-datta, who was one of the judges sitting on the stage. The latter overheard Gaṇapati and threw a challenge at him in the form of a verse:

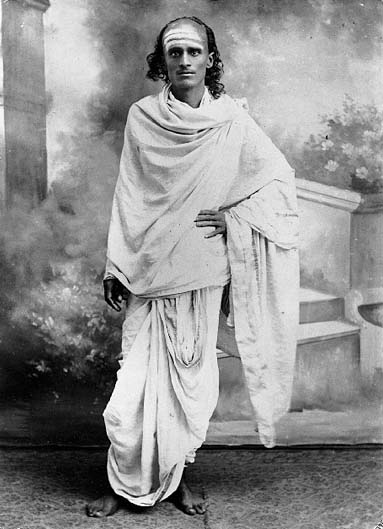

Ambikā-datta

सत्वरकवितासविता

कश्चिद्गौडोऽहमम्बिकादत्तः ।

“I am Ambikā-datta, a Bengali

I’m like the sun in the art of rapid composition.”

The first part of the verse is full of alliterations, and Gaṇapati-muni completed it by adding the next two lines to introduce himself:

Vāsiṣṭha-gaṇapati-muni

गणपतिरिति कविकुलपति-

रतिदक्षो दाक्षिणात्योऽहम् ।१।

“I am Gaṇapati, chief among poets

and a capable man hailing from the South.”

Ambikā-datta refers to himself as ‘some’ Bengali—kaścidgauḍaḥ—but Gaṇapati-muni asserts himself as a ‘capable Southerner.’ Gaṇapati-muni’s brilliance did not end there. He even added: “Bhavān ambikādattaḥ, ahamambāyāḥ aurasaputraḥ” – ‘You are Ambikā-datta, an adopted son of Ambikā. I am her true son, Gaṇapati.’

Ambikā-datta posed four samasyāpūraṇa challenges to him and the young Gaṇapati solved them all easily through verses that were rich in rasa and aesthetic beauty. He was then asked to explain verses from the Raghuvaṃśam and the Kāvyaprakāśa. While doing so, Gaṇapati made a mistake and used the adjective ‘sarveṣām’ in the masculine form instead of ‘sarvāsām,’ the feminine. Ambikā-datta noticed this mistake and criticised him for it.

Ambikā-datta

अनवद्ये ननु पद्ये

गद्ये हृद्येऽपि ते स्खलति वाणी ।

तत्किं त्रिभुवनसारा

तारा नाराधिता भवता ।२।

“Though flawless in verse,

how is it that you slip so pathetically

even with lucid prose like this

Have you not devoted yourself

to the Goddess of learning,

who is the essence of the three worlds?”

This time, it was Ambikā-datta who had made a grammatical error – he had said ‘tribhuvanasārā’ out of his love for alliteration, while the correct form would be ‘tribhuvanasāraḥ.’ It was Gaṇapati’s turn to ridicule him now. He said:

Vāsiṣṭha-gaṇapati-muni

सुधां हसन्ती मधु चाक्षिपान्ती

यशो हरन्ती दयिताधरस्य ।

न तेऽलमास्यं कविता करोति

नोपास्यते किं दयितार्धदेहः ।३।

“Have you not taken pains

to meditate on the coveted form of ardhanārīśvara

to achieve poetic skill that mocks nectar,

dismisses the sweetness of honey, and

even snatches away the lure of the beloved’s tender lips.”

Listening to Gaṇapati’s taunt, Ambikā-datta was enraged and expressed his anger through a verse:

Ambikā-datta

उच्चैः कुञ्जर मा कार्षी-

र्बृंहितानि मदोद्धत ।

कुम्भिकुम्भामिषाहारी

शेते सम्प्रति केसरी ।४।

“O arrogant tusker in rut, stop your trumpeting,

for here in the vicinity rests

the lord of the forest

after feasting on a herd of wild elephants.”

Ambikā-datta had erred again in the usage of one word – he had used ‘kumbhikumbhamiṣāhārī’ out of his weakness for alliteration, instead of the correct form ‘kumbhikumbhamiṣāhāraḥ.’ In reply, Gaṇapati poked fun at Ambikā-datta for his mistake through the following verse.

Vāsiṣṭha-gaṇapati-muni

समासीनो रसाले चेन्

मौनमावह मौकले ।

लोकः करोतु सत्कारं

मत्वा त्वामपि कोकिलम् ।५।

“O Crow! If you’re sitting on a mango tree,

be quiet, for you might be mistaken for a cuckoo.”

The verse added fuel to Ambikā-datta’s anger, who tried attacking Gaṇapati with another verse:

Ambikā-datta

ज्योतिरिङ्गणक किं नु मन्यसे

यत्त्वमेव तिमिरेषु लक्ष्यसे ।

“O Glow-worm! Nowhere but in pitch-darkness

can you fancy yourself.”

Gaṇapati completed the second half of the verse with:

Vāsiṣṭha-gaṇapati-muni

किं नु दीप भवने विभाससे

वायुना बहिरहो विधूयसे ।६।

“O Lamp! You can only hope to stay safe

within an enclosure,

as the wild winds might put you out

if you so much as venture out.”

Śitikaṇṭha-vācaspati, a scholar who was also present, intervened and tried to put an end to their fight. He asked them to conclude their argument with light-hearted verses about each other. Ambikā-datta started again and his taunts were now aimed not just at Gaṇapati, but at all South Indians.

Ambikā-datta

भट्टोऽखिलोऽट्टोपरि वारवध्वा

निपीय मध्वाऽऽरभते प्रकामम् ।

“All these Bhaṭṭas, giddy-headed

with their excessive drinking,

shamelessly squander away their time

with women who work for money.”

Gaṇapati immediately retorted with a dig at Bengalis.

Vāsiṣṭha-gaṇapati-muni

असुव्ययो वाऽपि वसुव्ययो वाऽ-

प्यमी न मीनव्यसनं त्यजन्ति ।७।

“Even if their life is at risk

and money is at stake,

these Bengalis will never give up

their addiction to fish.”

Gaṇapati won the poetry competition with accolades. Ambikā-datta, out of tremendous joy, gave him a friendly hug. Gaṇapati apologized for his temerity in attempting to challenge such a senior scholar as Ambikā-datta, who then composed and recited the following verse extempore:

Ambikā-datta

दत्तवानम्बिकादत्त

नीतये गौडजातये ।

मीनद्वयं विवादान्त्य-

पद्यपाठनिवेशितम् ।८।

“At the end of this literary debate,

this man has gifted two fish

to me, Ambikā-datta,

and to all our Bengali brethren.”

Ambikā-datta, through his verse, appreciated the sabhaṅga-śleṣa in Gaṇapati’s line ‘amī na mīnavyasanaṃ tyajanti.’ He thus recognized the genius in Gaṇapati and gave him his heart-felt appreciation.

Scholars assembled there awarded the title ‘Kāvyakaṇṭha’ to Gaṇapati-muni. This episode is unique because, unlike the debates between Śrīharṣa and Udayanācārya or between Vedānta-deśika and Ḍiṇḍima-bhaṭṭa, it ended on a positive note, with mutual respect and friendship.

Comments