Panini (पाणिनि) was a grammarian of ancient India. We do not know when and where he lived. 5th century BCE is a safe estimate. Today, the word ‘Panini’ connotes several things, of which the foremost is perhaps a computer-compatible, NASA-approved system of grammar. Over the decades, many learned minds have been engaged in extracting algorithms out of अष्टाध्यायी ('the eight-chapter book'), a treatise on Sanskrit grammar authored by Panini. The world of computers – though advancing at the speed of light – has not benefited from this ‘computer-compatible’ system. Apple and Microsoft still dominate the scene; Panini is nowhere to be seen.

Why is this so? Why haven’t the collective efforts of computer-scientists and Sanskrit vidvans yielded results? Because, everyone who clamors for advocating Sanskrit as a computer language fail to notice one important, basic point: Sanskrit, after all, is a human language (not taking into account its deified 'गीर्वाणी' status), and Ashtadhyayi has provided it a grammatical framework. As much as Sanskrit has the power to showcase the myriad shades of speech, it has no vital energy to activate computers. Any effort to make it do work that it isn’t equipped to do will be obviously futile.

Thinking of people who feel sad that Sanskrit has no computational features to offer, Einstein’s famous quote comes to mind – “… If you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” On the other hand, the ones who praise Sanskrit for its structure alone, remind us of Abhinavagupta when he said, “स तु दैवं विक्रीय यात्रोत्सवं अकार्षीत्” (“He sold the image of the deity and conducted a procession”).

Sanskrit has to be appreciated for its aesthetic value alone. However much it has been challenged, this has remained – and will always remain – an indisputable fact. Arjunwadkar, in his brilliant satirical work कण्टकाञ्जलि, has shown us the right way to look at Sanskrit:

सर्वासां जननी गिरां विबुधगीर्नो वा न जानीमहे

तस्यामेव हि संस्कृतिः श्वसिति वा नो वा न जानीमहे ।

राष्ट्रस्याभ्युदयस्तयैव भविता नो वा न जानीमहे

वाल्मीकौ तु दृढं रता मतिरिति प्रीणाति नः संस्कृतम् ॥Is she the mother of all languages, the chosen tongue of the wise? We don’t know

Is she indispensable for culture to breathe? We don’t know

Is the nation’s development possible only through her? We don’t know

Valmiki moves us deeply – and so, we love Sanskrit.

(Note: Hailing from Belgaum, Karnataka, Prof. K. S. Arjunwadkar was a distinguished scholar in Sanskrit and Marathi. He was proficient in grammar, literature, philosophy, and history, and was a champion of the Sanskrit revival movement. In 1965, he wrote Kantakanjali under the pseudonym ‘Kantakarjuna.’ It is a collection of satirical verses on the current affairs of those times.)

There is a huge corpus of literature in Sanskrit pertaining to almost all fields of human inquiry – politics, administration, astronomy, mathematics, sociology, medicine, philosophy; the language has given expression to everything. Seen in this light, it seems like a highly formal language with no room for artistic expression, much like an aged relative who opens his mouth only to say “no nonsense.” On the contrary, poetry, as is well known, is the heart of this language. Linguistic acrobatics that can be effortlessly performed with Sanskrit are unimaginable with any other language. With its rich vocabulary and intrinsic metrical rhythm, Sanskrit can express everything perceivable by our minds – with beauty and panache.

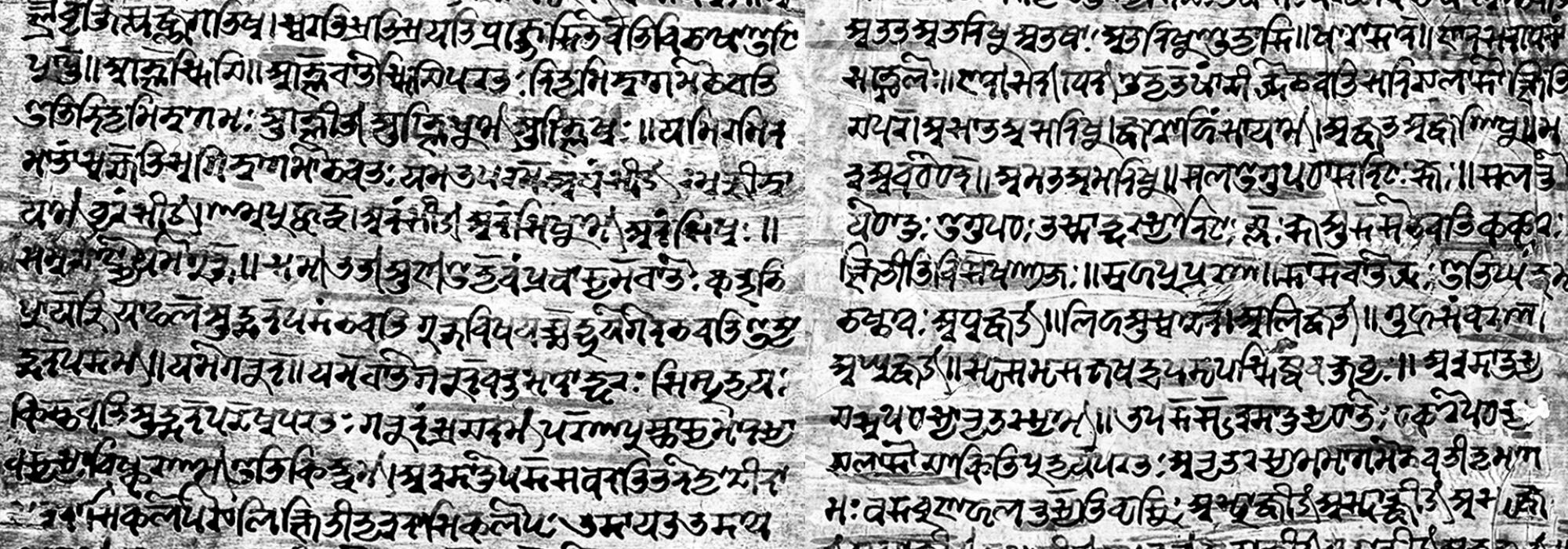

Panini is a fine representative of Sanskrit’s literary tradition; he is also one of its earliest torchbearers. His magnum opus Ashtadhyayi is well-known to all students of the language. Along with the inherent power of Sanskrit, it is this work that has made it ‘refined.’ (The word 'sanskrit' means 'perfected' or 'well-refined'). Thanks to Panini, Sanskrit is both robust and flexible.

Panini's creative prowess is in no way less than his critical acumen. He is said to have composed an epic-poem Jambvativijayam. Unfortunately, the work is not available to us. Few of his poems, however, have been preserved in सुभाषित anthologies like Subhashitavali, Suktimuktavali, Subhashitaratnakosha, Saduktikarnamrta, and Sharngadharapaddhati. His poems are marked by fresh imagery and lucid diction. Though he was a great grammarian, his style is simple. It is not ornamented or pedantic. With a keen eye to notice even the subtle signs of nature, he captured them in his poems by using appropriate metres.

Let us have a look at some of his poems:

विलोक्य सङ्गमे रागं

पश्चिमायां विवस्वतः ।

कृतं कृष्णं मुखं प्राच्या

न हि नार्यो विनेर्ष्यया ॥

(Metre – Anushtup)Seeing the Sun light up

the West-lady’s face

East grew envious, and her face was dark

Indeed no woman is free of jealousy

Oversensitive people of our generation will criticize Panini for the last line. But hasn't the truth been spoken? There is probably no woman who isn't envious of her beloved’s paramour. Panini has given life to this universal truth in this verse, by taking sunset to a whole new dimension. Most of us regard sunrise and sunset as trivial. What is so special about the Sun doing his job, we ask. Thinking of sunset, for instance, the direction bulbs in our brains get activated, and the West glows bright while East turns dim. That’s it. We do not even notice the gradual shifting of colors, let alone imagine the Sun’s romance. But what has Panini done here?

By personifying the subjects of his poem – Sun, East, and West – he has brought them closer to us, and in the process questioned our conception of animate and inanimate things. He has employed pun (श्लेष) to brilliant effect: Praci (East or first wife) and Pashcima (West or second wife), with the Sun sandwiched between them, don’t fail to delight the readers. Also, the undertones of the words रागम् and कृष्णम् paint a beautiful picture of a blushing West and a distraught East. The readers, smiling gently by now, cannot help thinking about the mood swings of their beloved. Panini reserves his thoughts for the fourth line. He leaves us there to muse indefinitely – “There’s no non-jealous woman.” Thanks to him, envy and jealousy are no longer bad words.

Here is another verse on the Sun. The poet says: Having finished his work, the Sun has gone away. Escaped like a criminal. Why, what did he do? Read on.

क्षपाः क्षामीकृत्य प्रसभमपहृत्याम्बुसरितां

प्रताप्योर्वीं कृत्स्नां तरुगहनमुच्छोष्य सकलम् ।

क्व सम्प्रत्युष्णांषुर्गत इति तदन्वेषणधिया

तडिद्दीपालोका दिशि दिशि चरन्तीव जलदाः ॥

(Metre – Shikharini)Nights are shorter and rivers robbed of water

Plants have gone dry. The entire earth is burning

“Where’s the Sun?” “He is responsible for all this” – Thinking thus,

clouds, with lightning-eyes, are looking for him in all directions

The Sun evaporates water from rivers. At its peak, it also burns trees and turns nights shorter. All of us are aware of these natural phenomena. We also notice the shifting of clouds and wonder where they are headed. Panini, it seems, did the same too. In this verse, he has presented his observations with added poetic flavor.

Soon after the sweltering heat of summer receded, rain-bearing clouds gathered together to formulate a plan. They planned to catch hold of Sun who, during summer, had bothered not just them, but the entire earth. They set out in all directions, looking sharply with lightning-eyes.

Such a novel imagination! Expressed in the meter Shikharini (of seventeen-syllables per line), this verse has an alluring charm.

A gifted poet has the ability to revitalize clichéd similes and dead metaphors. Treating with clinical precision, the poet imparts freshness to them. The following verse is a classic example of such a case. Likening the moon to a girl’s face has become so hackneyed that its mere presence in a poem is sure to generate a series of self-perpetuating yawns. It is probably the most used, misused, and abused idea in the history of ideas. Let us now see what Panini has done with it:

निरीक्ष्य विद्युन्नयनैः पयोदो

मुखं निशायामभिसारिकायाः ।

धारानिपातैः सह किं नु वान्त-

श्चन्द्रोऽयमित्यार्ततरं ररास ॥

(Metre –Upajati)Clouds with lightning-eyes

saw a damsel at dusk

Looking at her lovely face they roared

“With our mighty rains, has the moon fallen off too?”

The episode narrated here is simple: It's a rainy night. A lady is looking for her husband. There are some clouds in the sky, with occasional lightning. Employing a delightful figure of speech – भ्रान्तिमत् अलङ्कार – Panini has given the idea a new poetic spin. The confusion of clouds is not something we hear about every day. Not even in poetry. This makes us pause and think why they are confused. Here’s the answer: While going about their job and looking around with lightning-eyes, they chance upon an अभिसारिका – a lady looking for her beloved. It is immediately evident that she's beautiful. The clouds are now in a state of excited confusion. They muse aloud in the form of thunder – “Along with the rains we sent down, did the moon slip out too?” The suggestion, needless to say, is that the lady’s face is beautiful like the moon. There. Face and moon in one sentence. But no yawns this time. The way Panini has embroidered details around this rather plain episode has given it a surreal, even sublime twist.

Till now, we have seen Panini’s descriptions which, readers with varying degrees of sensibilities, may describe as cute, beautiful, wonderful and so on. In the present verse, we have the sage Panini giving us a piece of his mind. This seemingly innocent verse is packed with insights.

अथाससादास्तमनिन्द्यतेजा

जनस्य दूरोज्झितमृत्युभीतेः ।

उत्पत्तिमद्वस्तु विनाशवश्यं

यथाहमित्येवमिवोपदेष्टुम् ॥

(Metre – Upajati)Sun, the one of unmatched splendor, has now set

teaching man, who is unafraid of death,

a lesson, as it were –

All things alive must die someday

That Panini can describe the same sunset in so many ways speaks volumes about his inexhaustible creative faculties. The Sun is presented here as a grand old man who, having lived a full life and ‘ready to pass on to the next stage,’ says, “All things alive must die someday.” “Like me.” The inevitability of death is hinted here. The adjectives used to describe sun and man are noteworthy. He has described the Sun as अनिन्द्यतेजाः – of unmatched splendor (also of unsullied fame), pointing at its unblemished nature. Man is called दूरोज्झितमृत्युभीतिः – one with no fear of death. This shows his audacity. If one looks beneath the innocuous veneer, traces of several figures of speech can be found in this verse: हेतूत्प्रेक्षा, काव्यलिङ्ग, and निदर्शन.

Here is yet another verse describing sunset:

सरोरुहाक्षीणि निमीलयन्त्या

रवौ गते साधु कृतं नलिन्या ।

अक्ष्णां हि दृष्ट्वापि जगत्समग्रं

फलं प्रियालोकनमात्रमेव ॥

(Metre – Upajati)The lake closed her lily-eyes

When the Sun took leave for the day

This indeed is a virtuous act.

To the eyes that behold the entire world,

There’s but a single gift –

The beloved’s lovely sight

There are two kinds of people who view the world as an undivided whole: poets and philosophers. Panini was both; so, it isn’t surprising that he saw connections everywhere. This, coupled with his ever-fresh imagination, has worked wonders in this verse.

The lily closes its petals when the Sun sets. Looking for a reason for this, Panini says साधु कृतं नलिन्या – It is a virtuous act. We wonder what is virtuous about it. He says, the eyes enjoy the sight of the beloved alone. Also, it isn’t like the eyes are fixed on the beloved all the time; they have the freedom to look around. Though they behold everything, their enjoyment, no, fulfillment is at the sight of the beloved.

Likening the closing of the petals to the closing of eyes is beautiful in its own right. But here, the poet has gone one step ahead and supplemented it with a general statement – अक्ष्णां हि दृष्ट्वापि जगत्समग्रं फलं प्रियालोकनमात्रमेव. This wonderful insight into the nature of love has given the verse a majestic elegance.

To conclude, we can examine Panini as the creator of a bombastic verse. Here is a picture of an old vulture in a graveyard, devoid of extraneous additions from the poet. We can say that Panini saw this happen and wrote it down as best as he could. He wants the readers to enjoy the unadulterated beauty of the scene; so he does not distract us by adding a golden frame around the picture.

चञ्चत्पक्षाभिघातं ज्वलितहुतवहप्रौढधाम्नश्चितायाः

क्रोडाद्व्याकृष्टमूर्तेरहमहमिकया चण्डचञ्चूग्रहेण ।

सद्यस्तप्तं शवस्य ज्वलदिव पिशितं भूरिजग्ध्वार्धदग्धं

पश्यान्तः प्लुष्यमाणः प्रविशति सलिलं सत्वरं वृद्धगृद्ध्रः ॥

(Metre – Sragdhara)On a corpse burning in a funeral pyre

Landed a vulture old but strong

Flapping wings noisily, full of pride

It tore off from the fire ablaze,

Chunks of flesh with its mighty beak

With meat half-chewed and burning insides,

Look! It plunged into the water at once

The beauty of this verse can only be enjoyed by reading it out loud. We enter the verse to the flapping of wings, and exit with the knowledge that it is the doing of an old vulture. The stuff in between pushes us into cumulative cycles of dread, disgust, and amazement. The deep breath we initially took to recite this twenty one-syllable-long Sragdhara verse comes out all at once in the end. The sound of सत्वरं वृद्धगृद्ध्रः continues to ring in our ears, long after the words escape our mouth.

Panini’s contributions to grammar and linguistics are akin to that of Newton and Einstein to science. 2,500 years after its composition, Ashtadhyayi has still remained an insurmountable peak. It is a text that codified Sanskrit grammar in four thousand sutras (aphorisms). Unlike other systems of grammar, Ashtadhyayi is a descriptive treatise rather than a prescriptive one. In the text, each sutra logically leads to the next, thus preserving its organic unity within the systematic framework.

Reading Panini’s poetry makes us emotionally more receptive, and Ashtadhyayi stretches our intellectual abilities to the limits. In a world where IQs and EQs gauge a person, this is an invaluable gift. His works are a strong reason for us to take pride in our heritage.

References

Ganesh, 'Shatavadhani' R. Kavyakalpa. Hubli: Sahitya Prakashana, 2011. pp. 120-28

Krishnamoorthy, K. Panini. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2010