Quest for Truth in a Regime of Technology

One of the central aspects of Dr. S.L. Bhyrappa’s philosophy of writing is the fact that he regards it as a quest for truth. On a broader scale, it is an investigation of values—both human and philosophical. In this backdrop, how does one evaluate the cow as a value in and by itself? More so in an era of rampant and perpetually changing technology, which has come at the expense of all-encompassing erosion of values which were until recently regarded as unchangeable and timeless. More importantly, in a unique country like India which is the last surviving ancient civilization in a largely unbroken form. In the present time, on the political and social planes, India is also a complex battleground with ongoing clashes among alien religions, cults, worldviews, and mindsets where no settled outcome is visible in the foreseeable future.

The aforementioned erosion of enduring values has occurred on two major planes, both interrelated. The first is what came to be known as moral relativism where there is no good and evil, no right and wrong, nothing is superior or inferior, and that everything is just a matter of perspective. The second is the consequence of the first, which was easy to achieve once moral relativism became pervasive: the destruction of the very foundation of these lasting values. In his classic The Closing of the American Mind, Allan Bloom captures this phenomenon quite brilliantly.

So indiscriminateness is a moral imperative because its opposite is discrimination. This folly means that men are not permitted to seek for the natural human good and admire it when found, for such discovery is coeval with the discovery of the bad contempt for it. Instinct and intellect must be suppressed by education. The natural soul must be replaced with an artificial one…[R]elativism has extinguished the real motive of education..Nature should be the standard by which we judge our own lives and the lives of peoples. That is why philosophy, not history or anthropology, is the most important science…Cultural relativism destroys both one’s own and the good. [Emphasis added]

The other central trait of technology is speed, which translates into all-embracing restlessness in everyday human life leaving little time or intellectual space for deeper inquiry. Intellectual repose is one of the basic prerequisites for philosophical contemplation that eventually realizes its fruition in Darshana, a word for which there is no English equivalent. When this occurs over a prolonged period, eternal philosophies like those embodied in the Vedanta texts and the Bhagavad Gita not only become redundant but inaccessible because the very equipment required to accurately understand them would have been destroyed, replaced by restlessness and a daily struggle against numerous conflicts within. The explosive rise in expensive psychiatric centres all over the world is the direct outcome of this phenomenon.

Extraordinary Clash of Values

Thus, what were unquestioned and settled truths of both the outer and inner life during the elder Kalinga Gowda’s time are not only meaningless but superstitions which have no material use for his own grandson. The unlettered elder Gowda finds enormous pleasure in listening to the melodious strains of his son Krishna’s flute, takes solace in the simple but profound insight of Puranic stories narrated by his friend, the Jois, and is moved to tears by a few stanzas of a folk lyric:

‘pon ejecting I became dung, ‘pon patting I became dung-cake

‘pon burning I became the sacred ash for the forehead

applied without patting, I became manure

what good have you done to anyone, O Human?‘pon extracting I became milk, and became curd ‘pon hardening

became butter when curdled.

I became fine ghee when heated

what good have you done to anyone, O Human?I seek dirt and grass on the wayside and on the streets and Munch on them, return home and give elixir.

And drinking it you betray me. Tell me

what good have you done to anyone, O Human?

A more profound or moving commentary on the tenet of fact-value cannot be written.

But the younger Kalinga Gowda has not only forgotten this song but lives a life wholly opposed to that of his grandfather’s. This unfolding of this conflict is one of the most powerful expositions of the conflict between Dharma and Artha, or more accurately, what happens when Artha is pursued for its own sake shorn of Dharma. The elder Gowda—like his villagefolk—abides by the ancient Sanatana value that milk should not be sold. His grandson not only industrialises milk production and its sale but uses the lineage of the very cows his grandfather regarded as Mata or the Divine Mother. Even worse, America has transformed him into a guiltless beef-eater. This brutal alienation from his roots reaches a climax when he eats beef that his wife has prepared after slaughtering one of the cows belonging to the sacrosanct Punyakoti stock. Even in this case, he feels no guilt at eating her flesh but fear of the repercussions from his villagefolk. Orphanhood couldn’t have had a more savage definition than this.

Similarly, where the elder Gowda regarded agriculture and farming with all the sacred value attached to the notion of the earth as mother, his grandson regards it just as an economic resource. Where the elder Gowda grew food, his grandson grows tobacco because it is enormously profitable.

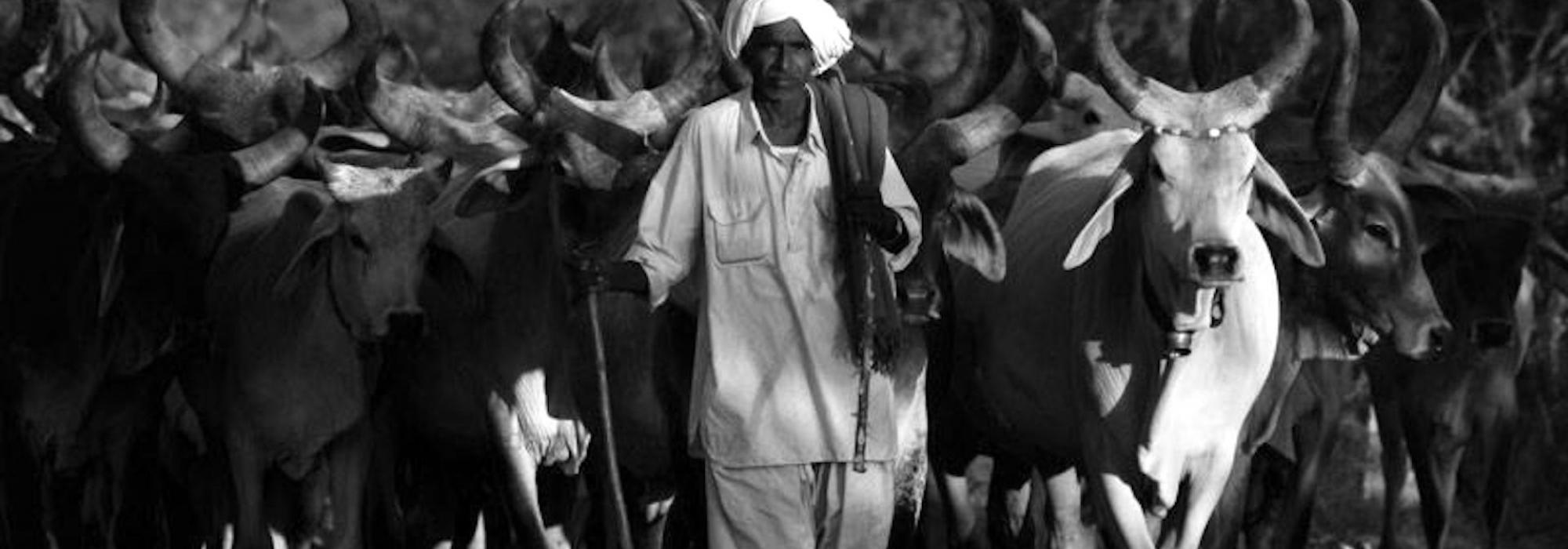

Centrality of the Cow

The centrality of the sanctity of the cow to the Indian civilization, culture and daily life is beyond question. It is one of those hoary and unparalleled cultural inheritances that must be valued, protected, upheld, and preserved for its own sake. If one were rooted in a healthy and sturdy value system, the status of the cow in the Hindu culture and psyche should ideally be placed outside the purview of public debates which have progressively yielded nothing but animosity and violence, forget any amicable resolution.

Perhaps few literary works have portrayed this sacredness as effectively, as powerfully, as endearingly and as movingly as Tabbali. There is no dearth of traditional Dharmashastra and Puranic texts that extol the divinity of the cow. And these texts should be preserved for the value that they bring to the proverbial rustic believer. However, Dr. Bhryappa’s splendid achievement is the manner in which he weaves this tradition in contemporary Indian life using an unassailable narrative mix of intellect and emotion, both inseparable. It can be more accurately called a Mimamsa that occurs on three planes: Adhibhuta, Adhiyajna and Adhyatmika as we shall see.

The fact that reverence for the cow and her worship is in the Hindu DNA is certainly not accidental. However, the answer to the question of why the cow enjoys a divine status apart from all other life forms cannot be found in subjective academic disciplines like sociology and anthropology. Indeed, there is almost nothing in our culture that does not contain moving, vivid, and elevating episodes related to the cow. Puranas, poems, prose, folklore, short stories, sculptures, temples, painting, Harikathas are replete with this. Indeed, some of the most popular and acclaimed episodes in our literary annals relate to the cow. Sri Rama’s ancestor Dilipa is prescribed the service of the cow as a Vrata. He offers his own life to a lion to save Nandini, the cow. Vishwamitra, in his former life as a haughty emperor aspires to become a Brahmarshi solely owing to a cow. Satyakama Jabali realizes the knowledge of Vedanta after serving an entire herd of cows. Indeed, even more fundamentally, the Santana tradition which depicts Dharma using the four legs of the cow is really ancient.

Given all this, the attempt of tracing the fount of the Hindu inner reverence for the cow using sociology, anthropology, and economics is actually hilarious. It is akin to tracing the reproductive cause of a snake in a grain of sand.

However, the same question confronts us when we constrict the cow’s primacy to just the economic realm: why did only the cow attain such divine status compared to all other livestock regarded as economic units? Compared to the cow, even the bull and ox occupy secondary status in the Sanatana tradition. We can glean an answer to this from D.V. Gundappa’s words:

The impact and pull of inner conviction is far more powerful and enduring than external circumstances and facts.

Thus, when we extend one person’s inner conviction of this sort to the entire society and nation, it becomes a cultural treasure and national value. If we were to phrase it differently, the Indian national value called cow is one of the finest real-life illustrations of the transformation of Artha into Dharma.

The living, captivating symbol of all these contemplations, convictions, beliefs, and the sum total of all the puranas and literature relating to the cow is the character of the elder Kalinga Golla Gowda.

To be continued