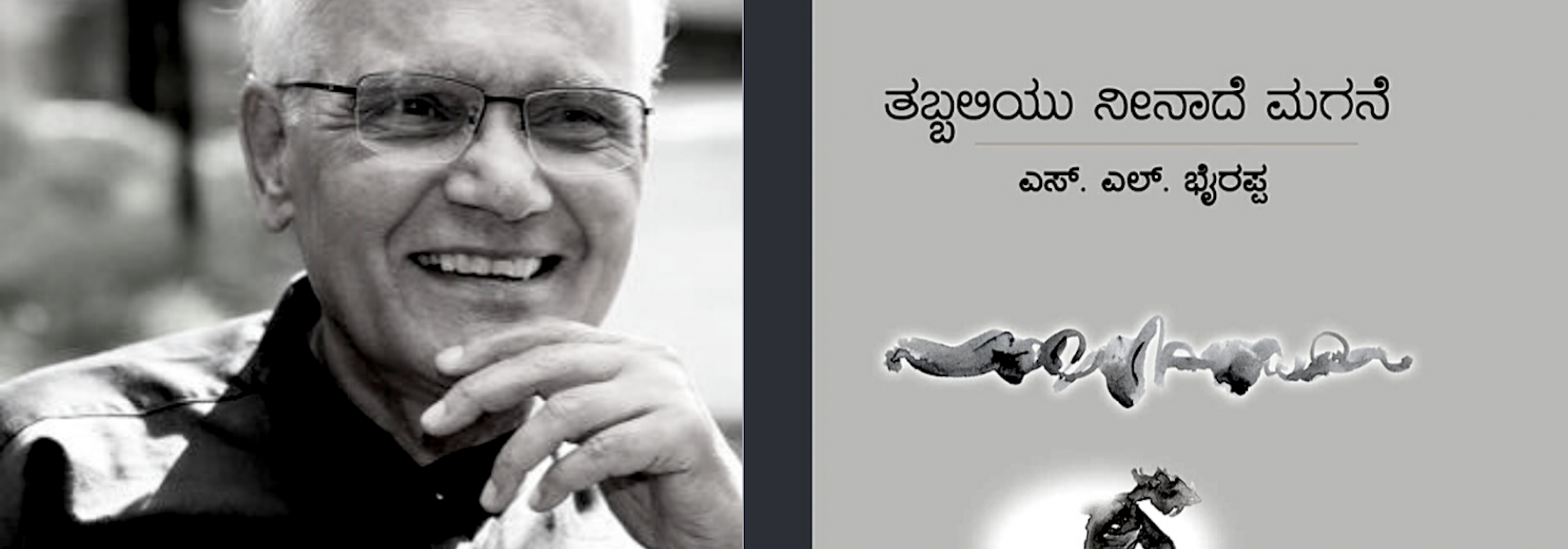

Like most of Dr. Bhyrappa’s major novels, Tabbaliyu Neenaade Magane is imbued with that stellar quality that transforms fiction into literature: universal appeal and an inbuilt capacity that re-attracts the reader to it. This is no ordinary feat given that the novel’s central theme is…cow. If we cast it in such a fashion, it immediately becomes reductionist, which it unfortunately has become over the last five decades. However, the exact theme of Tabbali is Sanatana Bharatavarsha, the Punyakoti cow, its distilled essence. Throughout the novel, she is looking askance, beseeching, beckoning, playful, perhaps still confident of her primacy in this Punyabhoomi…perhaps not. Like Punyakoti’s milk, the throbbing udders of the novel are perennial reservoirs of literary excellence, human drama, philosophical insights, and overlooked nuances of India’s cultural history. Like the Kalyani outside the Punyakoti Temple, the more we draw, the more quickly the reservoir in Tabbali fills up with freshness.

As the living embodiment of Dharma—a commercial transaction could be ratified by touching the cow’s tail—the cow is akin to Sakshi (insufficiently translated as “Witness”), the Inner Eye all of us possess, that is, our conscience. The act of touching Her tail is merely an affirmation that all of us do indeed possess a conscience. Which in turn is a direct commentary on the refinement of a national culture that has birthed and sustained such an extraordinary conception of life and values for thousands of years. Which in its turn is also a stark commentary on the indescribable downfall of such a culture when we notice that India is the world’s third largest exporter of beef for a few decades since independence. Which raises further questions on the true meaning of independence.

From this cultural kernel, the implication that emerges is unambiguous: the slaughter of the cow is the slaughter of Dharma and the slaughter of conscience. The fact that the same geography today requires a special law to ban cow slaughter where the cow was once a valid legal witness to a transaction shows how far and how unimpeded the march of the destruction of Dharma has occurred.

This phenomenon can also be explained as the gradual and manmade triumph of arthaika drushti (the pursuit of wealth for its own sake and as the ultimate and only end) over bhuta daya (compassion towards and affectionate cohabitation with all sentient beings). Bhuta daya reduces in direct proportion to this mindless pursuit of wealth for its own sake, which in turn erodes culture at the proportional pace. In Tabbali, this is shown in the character of the fabulously wealthy Hindu owner of a cattle slaughterhouse in Mumbai who perceives nothing wrong in the yawning dichotomy between his pilgrimages to Kedarnath, Manasasarovar and Kashi even as he profits from industrial-scale cow slaughter. In sharp contrast, we have the entire Kalenahalli villagefolk who preserve the sanctity of the cow in the only way they know: the unbroken traditional way.

The continuing debate between the human’s economic needs and progress and compassion towards animals—generally speaking, nature—is fairly recent: dating back roughly to the industrial revolution which destroyed nature at a scale and speed unprecedented in all human history until then. In the same duration, humans have also almost completely forgotten the pre-industrial age history. However, this essay is not the place for that discussion. This much can be summed up: the conception of bhuta daya as envisaged in the Sanatana tradition is fundamentally absent in the West. While it rejected Christianity as a practicing religion and a social and legal code following the Renaissance, its attitude towards nature continues to be informed by the Christian dogma which holds nature as being created by God for the enjoyment of Man.

Intertwined in these themes are some splendid insights on the real meaning of cruelty and violence especially in the remarkable episode of the Maramma festival where buffaloes are sacrificed to the Goddess. And in the evening when devotees walk on hot coals on bare feet. Tayavva is one of these devotees.

The layers are almost infinite.

Indeed, Dr. Bhyrappa can be called the king of dhwani (suggestion) and his every major novel resonates with multiple dhwanis at the same time, one of the hallmarks of classical literary works. The fact that they are also embedded with solid scholarship (unfortunately, over time, this has been dumbed down to that tepid word, “research” in public perception) lends a rare and unique blend in all of Indian literature. However, in the scope of my limited reading, and following Dr. Bhyrappa’s aphorism that in his view, literature is a quest for truth, one can reasonably arrive at a summary of sorts: Literature is above and beyond literary criticism and analysis; Life transcends literature, and Truth is greater than art. Or as Razia/Lakshmi says in Aavarana, “the creative work of an artist must be an expression of truth.”

Words that apply one hundred percent to the author who wrote them and whose awe-inspiring literary corpus is the living testimony of. Dr. S.R. Ramaswamy has coined a brilliant, term to describe Dr. Bhyrappa, a term that has all the qualities of being a honorific: nishkampa-dIpa: Unflickering Flame.

****

So far, I have attempted to merely skim the surface of a few major aspects in Tabbaliyu Neenaade Magane. This classic of Indian literature awaits the pen of a more accomplished and competent writer to do the full, glorious justice it deserves.

Concluded