This paper by Shashi Kiran B N and Hari Ravikumar was presented at the international conference New Frontiers in Sanskrit and Indic Knowledge in June 2017 organized by the Chinmaya International Foundation.

~

Abstract

Sanskrit, one of the greatest gifts of India to the world, is unique in many ways. The Pāṇinian system of grammar, logical in its structure and exhaustive in its delineation, gave the language great strength in terms of word-generation ability, brevity, and freedom from ambiguity.

The pedagogy of language learning that is widespread today cannot be applied as is for Sanskrit education. Individuals (Sri Satchidanandendra Sarasvati, R G Bhandarkar, A A MacDonell, D N Shanbhag, Michael Coulson, etc.) and organizations (Samskrita Bharati, Benaras Hindu University, Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan, Sura Saraswathi Sabha, Karnataka State Open University, etc.) who have worked towards teaching Sanskrit in the modern world have evolved their own methodologies, some of which work while some other do not. The present study draws from the best of the existing literature and posits that a kāvya-centric approach to learning is far superior to other approaches found in the surveyed pedagogies, both Eastern and Western.

The method of learning proposed in this paper stems from the traditional pedagogy but uses technology to optimize the process of self-study. An additional feature of the proposed method is that it takes into account different kinds of learners, categorizing them into four groups, viz., (i) the newcomer, who has never encountered the language, (ii) a person who is familiar with the Indian ethos but is unfamiliar with literature in regional languages, (iii) a person who is familiar with both the cultural heritage of India and the traditional literature in at least one Indian language, and (iv) a person who has formerly studied the language, either formally or otherwise, and wishes to reconnect with it.

The authors have identified eight learning tools which will be appropriately tailored to suit the needs of the different learner groups. The existing framework comes with the possibility of individual students customizing the module to match their tastes and efficiency. The learning tools are eight in number and are enlisted as follows:

- Exposure to classical Indian arts and culture,

- Listening to various samples of Sanskrit verse and reciting the same,

- Learning the orthography—typically the devanāgarī script—and practising writing,

- Active engagement with Sanskrit literature in the form of stories, poems, and plays,

- Familiarity with vyākaraṇam (grammar) and koṣaḥ (lexica)

- Undergoing the traditional training in eight steps –

- vadanam (recitation of a verse by the guru, typically once)

- anuvadanam (repetition of the same verse by the student, typically twice)

- padacchedaḥ (word division)

- ākāṅkṣā (contextual questioning to aid understanding)

- anvayaḥ (rearranging the word order)

- vyākaraṇaviśeṣāḥ (grammatical rules and nuances)

- anye viśeṣāḥ (other nuances with regard to prosody, figures of speech, etc.)

- bhāvārthaḥ (overall import),

- Playing an assortment of games to enrich the learning, and

Image courtesy :- Google Image Search - Doing graded exercises to reinforce the learning.

Learners who employ the aforementioned language learning methodology will be able to actively use Sanskrit, be it for conversation, composing metrical poetry, or writing prose passages apart from reading and understanding the classics of Sanskrit literature that include the works of great poets like Vyāsa, Vālmīki, Kālidāsa, and Guṇāḍhya. This will doubtless be of great personal value to the students as it will connect them to the sublime thoughts of the world’s oldest civilization.

Keywords: Sanskrit / Pedagogy / Technology

~

Introduction

Hailed as the language of the gods, Sanskrit is enmeshed with Indian heritage. Any attempt to separate it from the Indian cultural milieu will be the undoing of the entire fabric of this ancient civilization. For millennia, Sanskrit was the lingua franca of the Indian people as well as the language of kāvya (poetry) and śāstra (knowledge, science).

The very word ‘saṃskṛtam’—the Sanskrit word for Sanskrit—means ‘put together well’ or ‘highly refined.’ The development and refinement of the language must have taken place for hundreds of years, if not thousands, before it could even take the beautiful form that we see in the oldest available work in Sanskrit—and the oldest known treatise in the world—the Ṛgveda Saṃhitā.

The Sanskrit Language

The ancient Hindus tirelessly worked on every linguistic aspect of Sanskrit, making it robust and flexible. Here is a brief overview of the strengths of Sanskrit:

- Phonetics: Sanskrit has a well-structured alphabet scheme, organized according to the production of the various sounds by the human voice. The sound production is based on four criteria – a. Sthāna (place of vocal origin), b. Prayatna (effort required to produce the sound), c. Kāla (duration of the sound produced), and d. Karaṇa (method of articulation).

- Vocabulary: Sanskrit has an inbuilt etymological structure by which words are formed from dhātu (root words). The upasargas (prefixes; twenty-two in number) and pratyayas (affixes and suffixes; e.g. kṛt, taddhita, sannanta) give variety to the language and also help in word generation. A new word that is generated can be understood by a reader who hasn’t encountered it before but has a basic understanding of the language. This word-generation power gives Sanskrit an enormous vocabulary, with the highest possibility of creating synonyms and antonyms.

- Euphonic combinations: Words (and syllables) are joined together by means of euphonic combinations known as ‘sandhi,’ thus enabling a natural pronunciation of words.

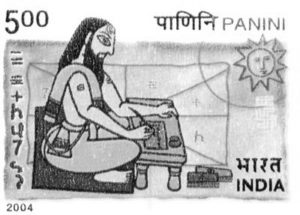

- Grammar: Sanskrit has a perfect, almost water-tight system of Grammar developed by the grammarian Pāṇini (c. 7th century BCE).

- Inflection: Sanskrit is a highly inflected language, with eight cases of noun inflection along with varied inflections in singular, dual, and plural forms for verbs and other substantives. This provides room for infinite variations of word order, thus making the language extremely flexible.

- Word compounding: The strength of inflection is further increased by the compounding of words—known as ‘samāsa’—which lends brevity to the language. This is an easier alternative to clausal constructions. Furthermore, the compounding of words facilitates dhvani (suggestive expression) – for instance, the Tatpuruṣa-samāsa can be understood in seven cases depend on the context.

With such a sophisticated and structured grammar, poetry became the natural means of expression. These strengths of Sanskrit have a direct bearing on prosody and poetry. This also gave rise to a great deal of exploration; for example, the art of citrakāvya is unthinkable in a non-Sanskritic language.

In spite of this, historically only a small percentage of Sanskrit scholars focused on poetry alone. Traditional wisdom opined that learning Sanskrit was a means to entry into the study of a śāstra.

The Difficulty of Sanskrit Studies

The problem with Sanskrit education today is manifold. Sanskrit is not a widely-spoken language like, say, English or Hindi, and therefore it becomes difficult to blindly imitate an existing pedagogy for language learning. For instance, the rather popular ‘immersion approach’ might not be effective because Sanskrit speakers aren’t found everywhere. On the other hand, Sanskrit is a living language, and it will be limiting to employ a pedagogy used for learning dead languages like Latin or Aramaic.

A section of Sanskrit learners regard the language as an artefact of pride and they have blind faith that somehow a knowledge of Sanskrit can improve their knowledge of science, particularly in the area of computing and natural language processing. There is no substantial reason to believe so. Further, many of the knowledge systems of ancient India—all recorded in Sanskrit—have developed and progressed in varied degrees of sophistication over time and in the modern context they don’t need the crutch of Sanskrit. There are also many such knowledge systems that have become outdated.

The result of these misguided notions is simply that the aesthetic employability of Sanskrit is largely ignored. The attempt of this paper will be to showcase the primary strength of Sanskrit in the context of the 21st century – its aesthetic and linguistic beauty. Needless to say, this aspect of Sanskrit has timeless appeal.

Overview of Sanskrit Pedagogy

The available pedagogy in Sanskrit education may be broadly classified into: a) Traditional gurukula method, b) Modern classroom method, and c) Self-study method. The present work concentrates solely on the third method since the aim of the paper is to prescribe a new self-study approach to learn the language, drawing from the best of traditional wisdom and modern techniques.

Pedagogues in the past who have designed Sanskrit learning material have typically approached it in four ways:

- Writing Sanskrit Primers. Perhaps the finest example in this category is the set of books authored in Kannada by Sri Satchidanandendra Saraswati Swamiji (Yellambalase Subbaraya Sharma in his pūrvāśrama). A few other noteworthy works include the ones by Shripad Damodar Satwalekar (in Hindi), Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan (in multiple languages), The Aurobindo Ashram (in English), Motilal Banarsidass (in English), Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratishthan (in Hindi and English), Sri Surasaraswathi Sabha (in Kannada and English), R S Vadhyar and Sons (in Malayalam and English), V S Apte (in English), R G Bhandarkar (in English), and Gary Tubb (in English).

- Writing Grammar Guides. Since the 19th century, several grammar guides have been written, starting from A A MacDonell. Excellent grammar guides have been published by Samskrita Bharati (in multiple languages). The works of scholars like Pushpa Dikshita (in Hindi and Sanskrit), D N Shanbhag (in Kannada), Chakravarthy Anantachar (in English), P K Duraiswami Iyengar (in English), and M R Kale (in English) are noteworthy.

- Preparing Conversational Sanskrit Texts. The efforts of Samskrita Bharati in this field are unparalleled. Apart from conducting conversation camps, they have produced several handbooks for easy learning of spoken Sanskrit.

- Preparing Sanskrit Readers. Scholars like A A MacDonell and Charles Lanman as well as the Sahitya Akademi—under the editorship of scholars like V S Agrawala, V Raghavan, K Krishnamoorthy, and Pullela Sriramachandrudu—have composed anthologies of Sanskrit literature spanning five millennia.

This list is by no means exhaustive. Several scholars and organizations have produced Sanskrit learning material in various Indian languages as well as foreign languages such as German, French, Russian, etc.

Due to the scientific structuring of the subject matter, many of these self-study books have made Sanskrit accessible to students from around the world. However, most of them singularly lack emphasis on the poetic aspect of Sanskrit.

Some of these works are graded according to the level of one’s learning but none of the existing methods take into account the variety of learners. Further, since a sizeable number of these works were composed before computers and the internet became ubiquitous, they do not consider the latest technological tools available for language learning.

With a view to bridge this gap, the present work takes a kāvya-centric approach. On the one hand, it uses a framework of learner profiles and on the other hand, it draws from various technological tools available today. The philosophy of this approach is simply that in the modern context, Sanskrit is best valued for its own sake rather than as a medium for other gains.

Eight Learning Tools

The authors have identified eight learning tools that can be tailored to suit the needs of different learner groups, as will be shown in the following section of the paper. This framework comes with the possibility of individual students customizing the module to match their tastes and efficiency. The learning tools are enlisted below:

- Exposure to classical Indian arts and culture.

- Listening to various samples of Sanskrit verse and reciting them.

- Learning the Sanskrit Alphabet – learning the pronunciation and then the orthography (typically the devanāgarī script).

- Familiarity with koṣa (Lexica) and vyākaraṇa (Grammar).

Image courtesy :- Google Image Search - Undergoing the Traditional Training in eight steps –

- vadanam (recitation of a verse by the guru, typically once)

- anuvadanam (repetition of the same verse by the student, typically twice)

- padacchedaḥ (word division)

- ākāṅkṣā (contextual questioning to aid understanding)

- anvayaḥ (rearranging the word order)

- vyākaraṇaviśeṣāḥ (grammatical rules and nuances)

- anye viśeṣāḥ (other nuances with regard to prosody, figures of speech, etc.)

- bhāvārthaḥ (overall import),

- Active engagement with Sanskrit Literature in the form of stories, poems, and plays.

- Playing an assortment of games to enrich the learning.

- Doing graded exercises to reinforce the learning.

In the structuring and implementation of each of these learning tools, technology will play a vital role. Various resources—both online and offline—provide great audio-visual learning material for the learners. Computer games specially designed for education offer a great model for further development in the domain of Sanskrit learning.[1]

Footnote

[1] Resources like YouTube have enormous audiovisual content, which can be employed in the service of Sanskrit learning. Audiobooks and animations are particularly valuable to ensure that the learning doesn’t become arduous. Softwares that recognize sandhis and poetic meters, e-books, and online dictionaries help simplify the learning process.

To be continued.