Vālmīki was absorbed in thoughts about his verse when Brahmā visited him: tadgatenaiva manasā vālmīkirdhyānamāsthitaḥ (1.2.28). He was tormented by the impropriety in hunting the male bird and the consequent anguish caused to its companion. Here is a poet mulling over the incident that inspires his poetry. If worldly events do not evoke such a profound response in a writer, they cannot inspire poetry. In its highest reaches, poetry is the emotional outpour of an inspired poet, bypassing conscious thought.

Brahmā put an end to Vālmīki’s perturbation:

श्लोक एव त्वया बद्धो नात्र कार्या विचारणा।

मच्छन्दादेव ते ब्रह्मन् प्रवृत्तेयं सरस्वती॥(१.२.३१)

What you have created is indeed a śloka. Have no doubt! I inspired your speech.

Brahmā, the Creator of this world with all its seeming incongruities, who stands beyond it, answered the crucial question: Is an emotional response to an ‘unjust’ facet of creation, poetry? What could be more appropriate! By this Brahmā has taught poets an important lesson in the art of good writing: they should strive hard to describe the tumult present in the events and characters of their works; having done so, they should maintain a good distance from it.

The appearance of Brahmā is most appropriate. Because he is the Creator and Vākpati, the Lord of Speech, he could inspire poetry, a novel form of verbal creation, in Vālmīki.

Vālmīki got the substance of his poem from Nārada and found its form in the śloka metre. We naturally tend to think that it was, then, easy for him to blend the two. We are mistaken. A bare storyline talking to the intellect should be enlivened by descriptions if it is to appeal to emotion as poetry. That is why Bhaṭṭa Tauta described a poet as varṇanā-nipuṇa. That is also perhaps why Rājaśekhara derived kavi, the Sanskrit word for poet, from the root kabṛ–varṇe, which means ‘to describe.’

Description is not just the vivid portraiture of the external world, as many people seem to think. It relates to the apt and clear narration of vibhāvas and anubhāvas, the causes and effects of emotion. The various mental states, the verbal and bodily means through which they show themselves, the activities of the world that triggered them – all of these find place in a piece of suggestive description that leads the readers to rasa.

Description requires an exact knowledge of the subject. To this end, the poet should have a perfect understanding of characters who take the story forward. Brahmā granted this ability to Vālmīki:

वृत्तं कथय वीरस्य यथा ते नारदाच्छ्रुतम्।

रहस्यं च प्रकाशं च यद्वृत्तं तस्य धीमतः॥

रामस्य सह सौमित्रे राक्षसानां च सर्वशः।

वैदेह्याश्चैव यद्वृत्तं प्रकाशं यदि वा रहः॥

यच्चाप्यविदितं सर्वं विदितं ते भविष्यति।

न ते वागनृता काव्ये काचिदत्र भविष्यति॥ (१.२.३३–३५)

Tell the story of the wise and valorous Rāma as you heard it from Nārada. Everything that he, Sītā, Lakṣmaṇa and the rākṣasas did, openly or in secret, known or unknown, will be revealed to you. Not a word in your poem will be untrue.

We can analyze this episode at various levels. At the level of belief (adhidaiva), Brahmā appears to have bestowed a boon on Vālmīki. At the level of innate feeling (adhyātma), Vālmīki appears to have engaged his inner vision. One is eligible to be a poet when he develops an insight into the world—both material and emotional—that is agreeable to its Creator. Only then will his words be free from the taint of falsehood. It is all right if a poet lacks erudition; his work will still be treated as poetry. However, if he lacks creative imagination, his work will not be treated as poetry.

Truth—and not mere fact—is pivotal to poetry. Ṛta, the immutable order that animates truth, manifests as beauty in art. And beauty is rasa. As far as literature is concerned, ṛta pertains to the emotional being of characters that breathe life into a story. A poet who does not know the nature of such ṛta distances himself from aesthetic verities. His work is a literary lie.

A poem that is true to ṛta is also true to rasa. It will last as long as rivers and mountains. The Rāmāyaṇa is such a poem. That is why Brahmā called it eternal:

यावत् स्थास्यन्ति गिरयः सरितश्च महीतले।

तावद्रामायणकथा लोकेषु प्रचरिष्यति॥ (१.२.३७)

Rivers and mountains here denote the dynamic and static aspects of the world.

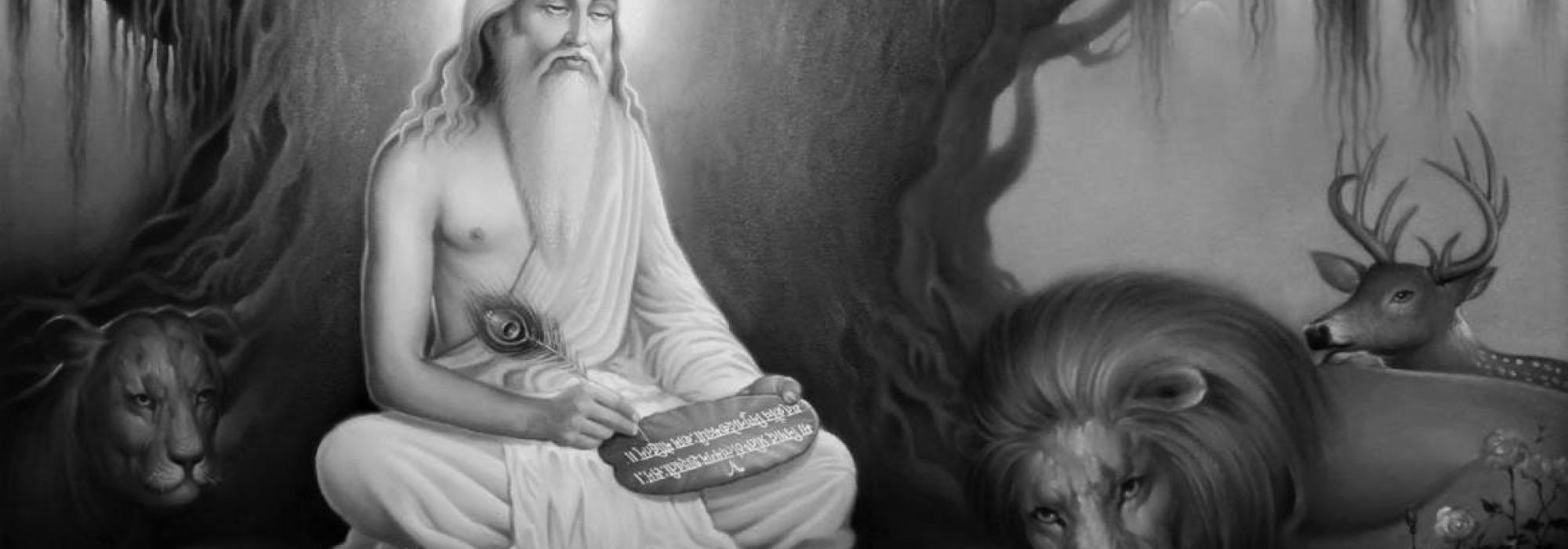

Vālmīki then did a purificatory ritual, sat on a mat of darbha facing East and contemplated on the events of his story. He could enter the hearts of all characters and understand their woes and wishes, fears and fortunes, thoughts and temperaments. His dharmavīrya made this possible (1.3.2–4). With yogic vision he could see Rāma’s story as clearly as a berry on his palm (1.3.6). While these details might appear supernatural on the surface, they relate to the poet’s singlemindedness. Poetic creation is a profound process. Looking at it superficially enfeebles poetry.

Lava and Kuśa presented the Rāmāyaṇa before an assembly of sages. They sang and recited with gusto, now plainly, now rhythmically. Vālmīki has gratefully recorded the response he received on that occasion: The overjoyed sages presented the boys with whatever they had or could immediately find. Their gifts included objects of daily use – everything from water bowls and mats made of grass to mauñjī and kaupīna! Some sages could not find anything. They gave the boys their hearty blessings.

This is a delightful account of the perfect way to present and appreciate poetry. It tells us how music can enrich literature and highlights the salience of rhythm in turning a poem into a song. It also draws our attention to society’s responsibility in supporting poets.

We can glean several literary tidbits from this episode, which is a veritable résumé of connoisseurship. Learned appreciation is central to the poetic process. Poets should never disregard their first readers. A poem that can captivate sages of clear conscience can surely entertain all audiences of refined sensibilities.

The fourth canto of Bālakāṇḍa and two cantos at the end of Uttarakāṇḍa inform us that Rāma invited Lava and Kuśa to present the Rāmāyaṇa before him. Rāma found the story so elevating that he felt it brings him good fortune: mamāpi tadbhūtikaraṃ pracakṣate (1.4.35). The protagonist here is not taking pride in the events of his life. Au contraire, he is demonstrating the ability of a true connoisseur to view and enjoy his own story from an optimum aesthetic distance, as though it were someone else’s.