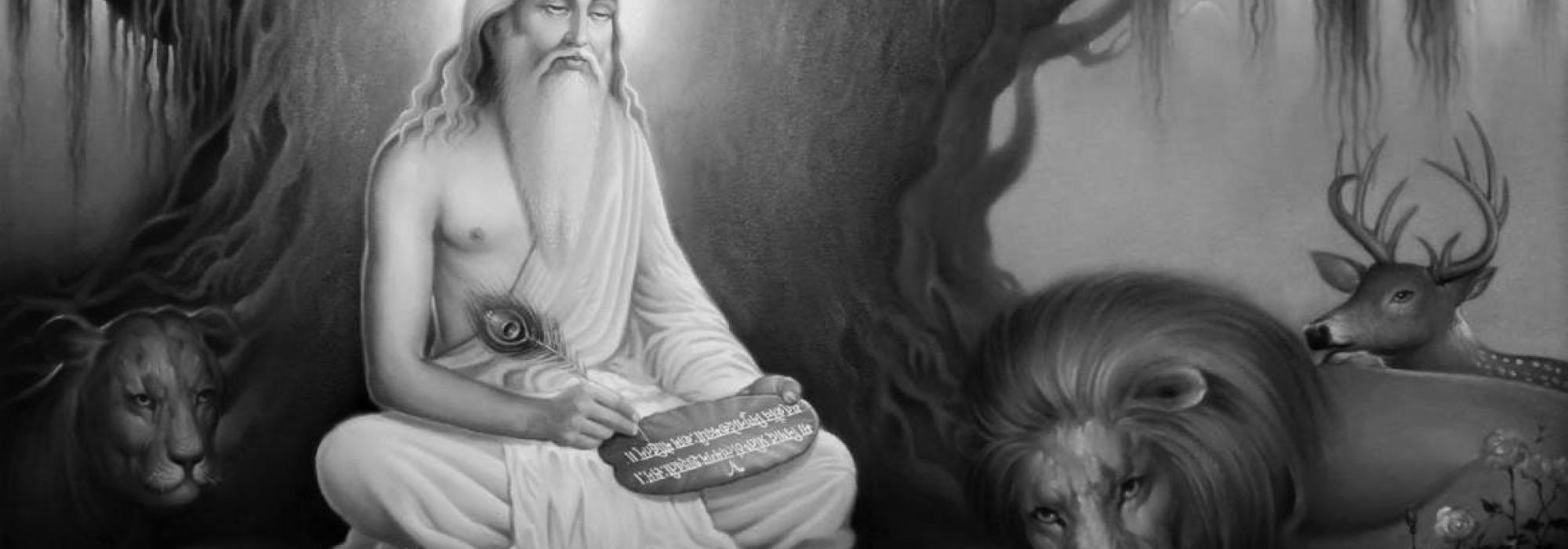

Maharṣi Vālmīki

The story narrated in the first four cantos of the Rāmāyaṇa is of great significance to the central concepts of the creative process: poet, poetry and connoisseur. In the opening canto, Ādikavi Vālmīki questions Maharṣi Nārada about the ideal human being, the model protagonist. This simple enquiry has far-reaching undertones. It has supplied flavour to the dry and rather unintelligible aesthetic dictum that expects the hero of a literary work to be of the dhīrodātta type – wise and magnanimous.

A sensitive poet eager to give a verbal form to his poetic vision understands well the importance of a good example, the epitome. Vālmīki found his example in Rāma. If the epitome is only a figment of the poet’s imagination, true connoisseurs might be unflustered; but readers seeking instructions in nobility will certainly be disappointed. That is why Vālmīki looked for a living example: ko nvasmin sāmprataṃ loke guṇavān (1.1.2), jñātumevaṃvidhaṃ naram (1.1.5).

The aesthetic value of a poem increases in direct proportion to the extent to which the protagonist portrays human emotions. A poet has the freedom to choose from a plethora of ‘characters’ – from plants and animals to deities and demons. However, he cannot create rasa without humanizing them. Knowing this full well, Vālmīki has made Rāma assert his humanness in unequivocal terms: ātmānaṃ mānuṣaṃ manye (6.120.11).

Most modern critics level an accusation at the literary tradition of Sanskrit: they say it lacks a ‘social conscience.’ Let us put this sweeping hypothesis to test and examine what emerges. Poets and scholars alike in India have held that poetry should propagate puruṣārthas, the goals of life, and assist us in the realization of cardinal human values such as truthfulness, non-violence and kindliness. This counts as social conscience. One might still claim that it is not shown on a large scale and count that as a lapse. Even so, the works of master poets provide ample material to correct it. A case in point is the long list of human qualities that Vālmīki likes to see in his protagonist, a list to which Nārada adds substantially at the beginning of the Ayodhyākāṇḍa.

The episode of a hunter bringing down one of a curlew-couple, along with Vālmīki’s response to it, shows us the poet’s sensitivity to human values.[1]

Vālmīki was once a hunter himself. He was not new to killing or the attendant cruelty. In this episode, he seems to be moved not by cruelty but the hunter’s lack of sensitivity to the ethics of his ways. Unlike humans, birds and animals have a specific mating period dictated by Nature. That mating is meant for procreation is evident. Animals and birds begin to mate as soon as the season conducive to the rearing of offspring begins. It is adharma to kill a mating animal. Living beings inexorably cause harm to others in order to promote and propagate themselves: jīvo jīvasya jīvanam. Nevertheless, dharma demands such harm be kept to a minimum. The hunter flouted this norm and invited the wrath of Vālmīki, who would discover himself a poet very soon. Because Vālmīki’s anger sprung from compassion and was primarily a response to the hunter’s lack of sensitivity to dharma, it neither destroyed the hunter nor brought back the bird to life.

Going by the meta-worldly nature of the Rāmāyaṇa, Vālmīki would have been justified in reducing the hunter to ashes, transforming him into a saint, bringing the bird back to life, or granting it all the puṇyalokas. Readers would not have found such a turn in the story inappropriate or off-putting. But he rose above such petty possibilities and acted in a natural manner that is worthy of emulation by all poets. This extraordinary stance conveys an ideal for great poets: they should strive for the sublime and not slip into romanticism.

Ever-alert sensitivity to human values is the defining trait of a poet. He does not have the king’s power to protect and punish. This does mean that he cannot rise in revolt against injustice. His revolt, however, asserts itself as rasa and not physical rebellion. In case the poet gets himself involved in revolt, it would be in his capacity as a conscientious citizen, the act having no bearing on his creative endeavours.

The first verse composed by Vālmīki stemmed from pity and not his experience of the karuṇa-rasa.[2] Its natural diction and cadence made him wonderstruck: “What is this I’ve created, caught in compassion for the fallen bird!” Śokārtenāsya śakuneḥ kimidaṃ vyāhṛtaṃ mayā (1.2.16). The verse was nicely divided into four equal feet, had the same number of letters in all lines, and could be sung to the tune of a lute. Vālmīki recounted these aspects of his plaintive utterance to Bharadvāja, his disciple, and named it śloka.

This is a remarkable instance of a poet being amazed by his own creation – one that has taken shape without his conscious effort. Events like this do not happen every day in the life of a poet. Vālmīki’s unpretentious response shows his modesty. He knew that he was but an accidental cause to his creation. Herein lies a valuable lesson: Candid acceptance of his position grants a poet the healthy distance from which to view his work. It paves the way for self-criticism. The poet will come to realize that he is only “an atom in the universe” and that his medium is in no way supernatural. Such realization, doubtless, will make him a better poet.

This event is also important from the perspective of literary aesthetics because it records the fascinating moment of a poet’s choosing his narrative medium, the metre. None of our poeticians has analyzed metres in terms of their appeal. Kṣemendra, the author of Suvṛttatilaka, is an exception. The poet’s ability to choose the perfect metre for an epic poem is one of the surest signs of his talent. Vālmīki suggests this wonderfully (1.2.18).

[1] A person unable to respond with warmth and compassion to the goings-on within and outside himself can never be a poet. Pratibhā, vyutpatti and abhyāsa (creative imagination, erudition and practice) are the prerequisites of poetry. Of these, pratibhā is an integral part of the ‘compassionate response’ described above. One who cannot experience intensely and compassionately has not in him the spark of pratibhā. Unfortunately, none of our aestheticians has brought out this aspect of pratibhā; they are all content to glorify it with high-sounding adjectives.

[2] Ānandavardhana was the first aesthetician to discuss this issue (Dhvanyāloka, 1.5). Following the Rāmāyaṇa closely, he observed that the śloka resulted from the poet’s śoka. Abhinavagupta, however, desiring to see all the details of the rasa-sūtra here, posited that the bird’s sorrow evoked karuṇa-rasa in Vālmīki. This is manifestly incorrect. It goes against his characterization of aesthetic experience as serene and not agitated.

The event showcases Vālmīki’s compassion born out of a consideration of dharma and adharma. It arose as a reaction and is quite unlike aesthetic experience that is free from desire and action. Were Vālmīki to experience karuṇa-rasa at that moment, he would betray no other response than ‘relish.’

Abhinavagupta calls an occasion-driven reaction deśa-kāla-viśeṣāveśa (Abhinavabhāratī, 6.31; vol. 1, p. 279) and considers it as a deterrent to aesthetic experience. The present episode exemplifies it. However, he insists that we see karuṇa-rasa and not mere pity here: na tu muneḥ śoka iti mantavyam (Locana, 1.5). We are at a loss to know why he was insistent on disproving his considered conclusions. This, in his own words, is akin to selling the image of a deity to get enough money to take it around in procession: sa tu devaṃ vikrīya tadyātrotsavamakārṣīt (Locana, 3.40).

This is an English adaptation of Śatāvadhānī R. Ganesh's Kannada work, Saṃskṛtakavigaḻa Kāvyamīmāṃse. To read the original click here.

To be continued.