DVG was a consummate polymath. He was many things at once: poet, scholar, journalist, political analyst, social worker, builder of institutions, democrat – the list is virtually endless. Evidently, the facets of his personality are varied and wide-ranging. Today I have been asked to speak on his accomplishments as a littérateur and outline his contribution to the study and practice of culture and philosophy. My friend Sri Sandeep Balakrishna will speak on DVG’s attainments as a journalist, statesman and the conscience-keeper of public life at large.

This apportioning of the subject troubles me, because I find it hard to draw a strict line of demarcation between the publicist and the man of letters. DVG himself did not compartmentalize his activities in this manner. On the contrary, he looked at life as an “undivided whole.” I request you all to bear with me if I occasionally step into a territory other than mine. I hope Sandeep won’t mind. After all, territorial conflicts arise between rivals, not friends!

I have divided the talk into three parts. DVG is a national treasure, and it is only right that all Indians should know him well. But given our wanton disregard for native scholars, many people outside of Karnataka do not know him. So, I shall begin by giving a quick overview of some of the events of his life. In the second part I shall introduce a few of his major works and try to identify the key features that undergird them. In the final part, adhering to the theme of this lecture series, I shall discuss the aspects of DVG’s thoughts and personality that students of Indian culture will do well to emulate.

* * *

DVG was born on 17.3.1887 in Mulbagal, a town in the Kolar district of Karnataka. Venkataramanayya and Alamelamma were his parents. His family was quite well to do at the time of his birth but was soon reduced to penury by a twist of fate. Quite early in life DVG learnt to endure hardships with courage – to ‘grin and bear’ as they say. The mountainous terrain of Kolar, a symbol of constancy, helped him steel his mind. Aunts and uncles who doted on him demonstrated the life-enriching values of love and affection. The unhurried life of humble townsfolk left a strong impression on the boy. DVG learnt various stotras and Vedic hymns from Brahmaśrī Veṅkaṭarāma Bhaṭṭa. The Guru instructed his disciple not just in Yajurveda but also compassion and contentment.

DVG made the most of his student days in Mysore and Kolar by lapping up the works of exceptional English writers: from Shakespeare and Tennyson to Morley and Gibbon. He was deeply influenced by the writings of Swami Vivekananda, particularly Lectures from Colombo to Almora. Before he turned twenty DVG had learnt what to value in life, had read widely and was exposed to the best thoughts of the East and West. He came to Bengaluru in the mid-1910s, poor in material resources but rich in knowledge and virtues.

In Bengaluru he pursued knowledge with greater vigour and tenacity. He was fortunate to find many mentors. While N Narasimha Murthy introduced him to the political classics of the West, K Ramachandra Rao, K A Krishnaswamy Iyer and M G Varadacharya sensitized him to the subtleties of English poetry. DVG studied classical Sanskrit poetry from Chappalli Viśveśvara-śāstrī and Advaita-vedānta from the colossus of traditional learning, Tarkapañcānana Hānagallu Virūpākṣa-śāstrī.

At the mundane level, he did odd jobs to make ends meet. He dabbled in all sorts of hackwork and kept accounts for a small workstead that painted horse carriages. Being married by then, he found it extraordinarily difficult to set up a home for his family. Then fate drew him to journalism. Although cut out for better things, DVG became a journalist and persevered for nearly seven decades to provide nourishing, wholesome food to a profession with an insubstantial appetite.

Inspired by Vajapeyam Venkatasubbayya, DVG began to take an active part in public affairs. Consequently, he was drawn to the rough and tumble of politics. With the support and guidance of enlightened statesmen such as Sir M Visvesvaraya, he endeavoured to instill a positive sense of community consciousness in our people and turn public opinion into a force for the good.

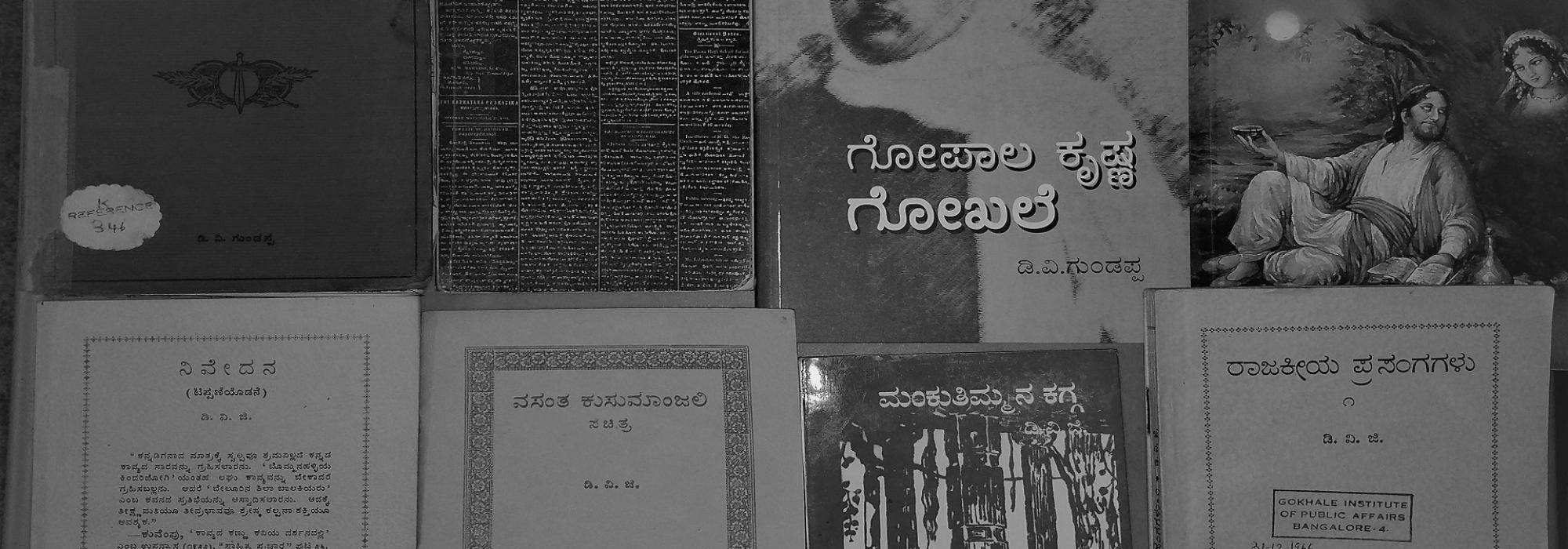

He founded and edited numerous newspapers and journals such as Sūryodaya-prakāśikā, Bhāratī, Sumati, Evening Mail, Mysore Times, The Karnataka, Karṇāṭaka Janajīvana mattu Arthasādhaka Patrikè, The Indian Review of Reviews and Public Affairs. He was a municipal councillor, member of Karnataka Legislative Council, senate member of the University of Mysore, member of the constitutional reforms committee of Karnataka, member of the executive council of the University of Mysore and the vice-president of Kannada Sahitya Parishat. He established and took an active part in organizations such as Popular Education League, Social Service League and Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs. He got down to the streets and served the public on multiple occasions: during the outbreak of the influenza epidemic, second world war and the Indian freedom movement.

Two statements actuated him to take up all these activities. One is by Svāmī Vidyāraṇya: “Jnāninā carituṃ śakyaṃ samyagrājyādilaukikam” and the other is by Gopal Krishna Gokhale: “public life must be spiritualized.”

DVG looked upon public life as a sacred service. And service accepts no reward. In keeping with this view, he maintained a healthy distance from riches. He did not cash even one of the many cheques that the treasury of the Mysore State issued for his services as a consultant to Sir M Visvesvaraya, the then Dewan. The ringing words of Bhagavān Manu struck a deep chord with him: yo’rthe śucirhi sa śuchirna mṛdvāriśuciḥ śuciḥ (Manusmṛti 5.106). He remained fiercely independent throughout his life, exemplifying courage, candour and trustworthiness. I would like to quote his own words to describe his attitude to journalism and public affairs:

If I may so put it, the journalist is the humble sanitarian who labours hard to bring sunlight and fresh air into the halls peopled by administrators and legislators. (Presidential Address to the Mysore State Journalists’ Association, 1932)

I feel that the country today has particular need of that type of public men who would serve without getting entangled in power politics … Let us keep out of the competition and do our best from outside the seats of power.

I have always viewed life as a supreme Leela – sport, if you please. As such, how could I fall into the error of making a missionary of myself? It is only people wanting in modesty that conceive great ideas of themselves and their so-called missions here. (Viraktarāṣṭraka DVG, p. 128)

The following was his considered opinion: Misery sweeps over us like unending waves of the ocean, while happiness presents itself drop by drop. We should never miss an opportunity to experience and spread happiness. In holding this view, he was inspired by Ācārya Cāṇakya’s words: na nissukhaḥ syāt (Arthaśāstra 1.7.3).

DVG was manly and hearty, brave and cheerful. To him, humour was an object of reverence and not casual indulgence. Even a simple act of deciding on a nickname for a friend was a serious business with him, requiring making lists and elaborate discussion. He enjoyed food. Once when he was binging on some fritters, Vidvān N Ranganatha Sharma, his good friend and a great scholar, came to see him. The woman of the house gave him a plateful of fritters. Ranganatha Sharma took just one and pushed the plate towards DVG, who quipped: “Sharma, your stomach is like a ladies’ wrist-watch; mine is like the Big Ben!” He once came across a book tilted Recovery and Remanufacture of Wastepaper and immediately exclaimed: “What an apt description of my profession!” Because he had this remarkable ability to laugh at himself, DVG never fell into the trap of self-aggrandizement.