On Bharata’s repeated use of ‘bhāva’ in words such as vibhāva, anubhāva and vyabhicāri-bhāva:

It should be noted that Bharata has coined all these technical terms retaining the core-term bhāva to emphasize the role of imagination on the part of the spectator. (Indian Literary Theories, p. 146)

Freedom is the hallmark of beauty:

The soul of creativity lies in a victory achieved over the burden of necessity, the burden of life, the burden of logic. Freedom is thus the hallmark of beauty and each alaṅkāra in Sanskrit books is not an ornament superadded, but an eloquent testimony to the boundless freedom the poet has chosen to allow himself. (Some Thoughts on Indian Aesthetics and Literary Criticism, p. 15)

The essence of prasāda-guṇa or perspicuity lies in the lucidity with which the poet can communicate his feeling to the connoisseur:

Raw emotion in life has no unity or pattern about it; it is spent about in practical action. But the poet’s emotion is without a touch of practicality and gets the serenity and detachment just enough to bring about an organized unity or patterning in his impressions of life, either direct or indirect. This organized experience is the poetic theme, and it naturally explains the patterned rhythms and images in the external form of the poem also. When a sahṛdaya surrenders himself to a poem, he understands intuitively whether the poetic content or rasa is successfully transmitted in the poem or not by the felt ease or difficulty in his sharing the poet’s meaning. That is why perspicuity is a poetic excellence and obscurity a poetic flaw. (Some Thoughts on Indian Aesthetics and Literary Criticism, p. 69)

On the poet’s experience of rasa:

Rasa is nothing more than aesthetic joy; hence the creative poet must perforce be credited with it. ‘If a pot is not full, it cannot overflow’ (yāvat pūrṇo na caitena tāvannaiva vamatyamum) … In this sense, the creative urge or inspiration itself can be regarded as rasa … The poet himself might appreciate his own work at a later stage after creating it. This is also rasa, but in another sense. We might distinguish the two as joy of creation and joy of appreciation; but there is only one word rasa in Sanskrit for both. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 15)

Similarity between Pāṇini and medieval Sanskrit poets:

If the grammar arrested the natural growth of the language, it also saved it from ‘linguistic decay’ and helped its preservation in its pristine purity, so that in respect of clarity, after a lapse of even two thousand years, the Sanskrit language remains unique and unparalleled. If Sanskrit poets failed to add new dimensions to their art, they uniquely succeeded in perfecting the poetic technique to its highest watermark in the history of world poetry. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 25)

The true meaning of alaṅkāra:

In their sense aspect, [words in poetry] acquire a heightening (atiśaya) or undergo a transfiguration which is the sine qua non of the poetic art. A synonym of alaṅkāra in this wide connotation is vakrokti or ‘oblique expression.’ To poetize is to deviate from the normally accustomed habits of speech and thought; in this sense, every truly poetic line will involve some deviation or turn and it cannot be devoid of alaṅkāra without ceasing to be poetry … Thus understood, the principle of alaṅkāra deserves to be approximated to the modern idea of ‘imagery’ in poetry. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 28)

On the correct meaning of śabda and artha as the ‘form’ and ‘content’ of poetry:

All the elements of the poetic art directed to please the ear came under śabda while artha embraced what we call the poetic theme or subject. The fusion of the two was the poetic process. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 58)

Sidelights on dhvani:

That even such an implicit follower of Ānandavardhana as Mammaṭa thought it better to avoid the very mention of dhvani in his definition of poetry is clear enough to show how this controversy [fueled by the opponents of Ānandavardhana] had done considerable damage to the theory of dhvani. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 111)

In the whole range of Sanskrit Poetics there is not a second work [after Dhvanyāloka] which exclusively treats of the Dhvani theory. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 112)

On decadence in Sanskrit poetry:

All the works written in this age of decadent taste may be said to be coins of the same mould, since we find everywhere the same literary flourishes and consummate conceits. The difference can be discerned only in the theme which serves no better purpose than a peg on which to hang their artificial display … These writers handle their materials as with a gloved hand … They were the victims of a convention (Kavisamaya) that sought in language a gaudy substitute for the thing instead of its close-fitting garment; and in the realm of pure poetry, where we look for lofty thought and vivid imagination, they were denied open vision and free soaring flights. They sang in a cage and not upon a branch. Though they wield language with such astonishing skill, they seldom work the miracles with it that proclaim the divine poet. The most brilliant electric light is not sunshine. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, pp. 203–04)

On Nāṭyaśāstra – need for interdisciplinary study in solving textual problems:

A clear picture can emerge only when specialists in the disciplines of saṅgītaśāstra, abhinaya schools and the ancient Indian stage sit together and sort out things in the light of the vast material available under each head in the different disciplines. This problem, I am afraid, cannot be tackled by Sanskrit scholars alone unassisted by interdisciplinary specialists. (Indian Literary Theories, p. 146)

* * *

At times, Krishnamoorthy gets carried away by ‘academic zeal’ and makes some unsound pronouncements. He offers a high mantle to every scholar on whom he chooses to write, regardless of their intrinsic worth. He tries to prove that ancient aestheticians such as Bhāmaha and Daṇḍī knew the concepts of aesthetic experience and poetic suggestion well. This is manifestly incorrect. One need not deny them a feel for rasa and dhvani; but crediting them with the logical formulation of these theories would be erroneous. Krishnamoorthy also tries to confer upon Udbhaṭa and Vāmana a high status that they do not deserve.

In some places, he makes entirely absurd statements such as this: “The existence of Vidūṣaka or the court-fool in the earliest dramas we know indicates that drama was meant mainly for princely entertainment and a select audience of critics trained in the rules of Bharata. The Sanskrit stage was never popular and we are unaware of any commercial theatre which ever put a Sanskrit drama on the boards.” (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 249)

His criticism of contemporary scholars such as V Raghavan, N Ranganatha Sharma and T N Sreekanthayya is driven more by personal bias than commitment to truth.

Above all, some of his views on rasa expressed in his Kannada monograph Rasollāsa and English articles such as “Rasa” as a Canon of Literary Criticism and The Riddle of “Rasa” in Sanskrit Poetics are extremely unsound. In Rasollāsa, he expresses dissatisfaction with Abhinavagupta’s explanation of rasa (p. 32) but does not propose a meaningful alternative to it. He posits that the rasa of plays is different from the rasa of poems (p. 47) and holds that rasa lies in the protagonist and not connoisseur (p. 55). In The Riddle of Rasa, he tries to arrive at the ‘original intention’ of Bharata regarding rasa, untainted by the views of Ānandavardhana and Abhinavagupta. This is like trying to understand Pāṇini without the aid of Kātyāyana and Patañjali, Vāmana and Jayāditya.

A neophyte would do well to begin the study of Krishnamoorthy’s works from two of his Kannada books: Samṣkṛtakāvya and Bhāratīya Kāvyamīmāṃsè tattva mattu Prayoga. The former presents Sanskrit poetry in all its richness and the latter introduces sound aesthetic principles essential to analyze all kinds of poetry.

* * *

Krishnamoorthy had a remarkable mastery over Sanskrit, Kannada and English. He read widely in all these languages and never took any of them for granted. Constant study and active usage helped him develop remarkable linguistic felicity. This happy blend of languages is a model for all times. Sanskrit grants access to our hoary past and forms the foundation for all studies related to India; regional languages help one stay rooted and see interconnections between seemingly unrelated subjects; English opens up new vistas of knowledge and offers a much-needed historical perspective.

Krishnamoorthy has referred to around twenty Western authorities and fifty Indian aestheticians, both ancient and modern. Though he mainly wrote on poetry and poetics, he drew data from a wide variety of primary sources in Sanskrit such as Vedas, Nirukta, Viṣṇupurāṇa, Bhāgavata, Śābarabhāṣya, Ślokavārttika, Tantravārttika, Ātmatattvaviveka, Nyāyamañjarī, Yogasūtras, Yājñavalkyasmṛti, Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, Mahārthamañjarī, Tantrāloka, Bhagavadgītā, Khaṇḍanakhaṇḍakhādya, Arthaśāstra and Kāmaśāstra. He was extremely thorough in his own subject. He had studied more than fifteen commentaries on the Kāvyaprakāśa alone, authored by scholars such as Bhaṭṭa-gopāla, Śrīvidyācakravartī, Govindaṭhakkura, Śrīdhara, Bhīmasena-dīkṣita, Viśvanātha, Māṇikyacandra, Caṇḍīdāsa and Vamanacharya Jhalkikar. Krishnamoorthy’s writings eloquently attest the fact that a sensitive scholar’s constant contemplation on a subject generates amazing insights. They inspire us to develop a broad perspective on our chosen subject.

As far as the study of Indian aesthetics is concerned, Krishnamoorthy inspires us to adopt an integrated approach:

The whole procedure of treating Indian poetics under so many schools— alaṅkāra, guṇa-rīti, rasa-dhvani, vakrokti etc.—is a misconception not borne out by facts; and the sooner it is abandoned, it is better for clarity … The mansion of beauty has many halls and all of them together constitute the whole. To dissect each part without reference to the whole is neither good precept nor good criticism. (Indian Literary Theories, pp. 36–37)

सोऽयं कल्पतरूपमानमहिमा भोग्योऽस्तु भव्यात्मनाम्

Bibliography

1. A. R. Krishna Shastri. Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Institute of Kannada Studies, University of Mysore, 1976

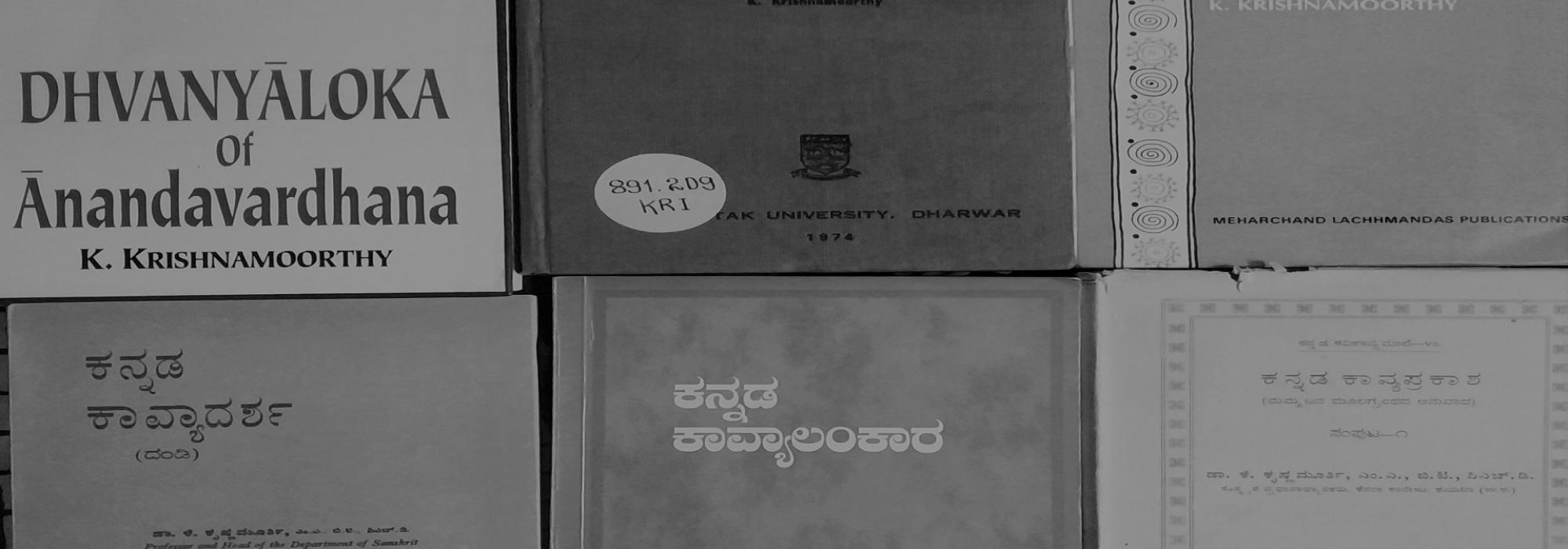

2. Abhinavagupta’s Dhvanyāloka Locana (with an anonymous Sanskrit commentary). Krishnamoorthy, K. New Delhi: Meharchand Lachhmandas Publications, 1988

3. Aestheticians. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broad-casting, Government of India, 2013

4. Alaṅkāraśāstre Kāvyavaividhyavādavimarśaḥ (Sanskrit). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: University of Mysore, 1955

5. Ānandabhāratī. Mysore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Felicitation Committee, 1995

6. Ānandavardhanana Kāvyamīmāṃsè mattu Kannaḍa Dhvanyāloka (Kannada). Krishna-moorthy, K. Bengaluru: Abhinava, 2007

7. Ancient Indian Literature (Ed. Sharma, T. R. S.; volume two). New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2014

8. Aspects of Poetic Language: An Indian Perspective. Krishnamoorthy, K. Pune: Board of Extra-Mural Studies, University of Poona, 1986

9. Basavaṇṇanavara Vacanamīmāṃsè (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2010

10. Bhāratīya Kāvyamīmāṃsè tattva mattu Prayoga (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Ban-galore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2011

11. Bhāratīya Kāvyamīmāṃsègè Dr. K. Kṛṣṇamūrtiyavara Koḍugè (Kannada). Shastri, C. H. Dharwad: Kapila Prakashana, 2012

12. Bhāratīya Sāhitya Caritrè (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Dr. K. Krishna-moorthy Research Foundation, 2020

13. Bhavabhūti (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Re-search Foundation, 2016

14. Dharmaśāstrada Itihāsa (vol. 5, part 1; Kannada). Mysore: Kuvempu Institute of Kan-nada Studies, 2011

15. Dhvanyāloka (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Directorate of Distance Edu-cation, University of Mysore

16. Dhvanyāloka of Ānandavardhana (with English translation). Krishnamoorthy, K. Del-hi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1982

17. Essays in Sanskrit Criticism. Krishnamoorthy, K. Dharwar: Karnatak University, 1974

18. Indian Literary Theories: A Reappraisal. Krishnamoorthy, K. New Delhi: Meharchand Lachhmandas Publications, 1985

19. K. Krishnamoorthy. Narayana Prasad, K. G. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2014

20. Kālidāsa. Krishnamoorthy, K. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2017

21. Kannaḍa Dhvanyāloka mattu Locanasāra (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Research Foundation, 2013

22. Kannaḍa Kāvyādarśa (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Dr. K. Krishnamoor-thy Research Foundation, 2013

23. Kannaḍa Kāvyālaṅkāra (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bengaluru: Abhinava, 2007

24. Kannaḍa Kāvyālaṅkārasūtravṛtti (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2010

25. Kannaḍa Kāvyaprakāśa (2 volumes; Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Sharada Mandira, 1956, 1959

26. Kannaḍa Kirātārjunīya (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Sharada Mandira, 1955

27. Kannaḍa Mṛcchakaṭika (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Dr. K. Krishnamoor-thy Research Foundation, 2017

28. Kannaḍa Pratimānāṭaka (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Dr. K. Krishna-moorthy Research Foundation, 2014

29. Kannaḍa Uttararāmacaritè (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krish-namoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2012

30. Kannaḍa Yajñaphala (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Sharada Mandira, 1958

31. Kannaḍadalli Kāvyatattva (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krish-namoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2010

32. Kavikaumudī of Kalya Lakṣmīnṛsiṃha (Edited with English translation). Krishnamoorthy, K. Dharwar: Karnatak University, 1965

33. Kavirājamārgaṃ (Ed. Krishnamoorthy, K; Kannada). Bengaluru: Kannada Sahitya Parishattu, 2015

34. New Bearings of Indian Literary Theory and Criticism. Krishnamoorthy, K. Ahmeda-bad: B. J. Institute of Learning and Research, 1982

35. Pāṇini (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2010

36. Rājaśekharana Kāvyamīmāṃsè (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Dr. K. Krish-namoorthy Research Foundation, 2014

37. Rasollāsa (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy San-skrit Research Foundation, 2011

38. Sāhityajīvi (Ed. Sheshagiri Rao, L. S.; Kannada). Bangalore: Prof. G. Venkatasubbiah Felicitation Committee, 1976

39. Saṃpradāna (Ed. Leela Prakash, L; Kannada). Mysore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Re-search Foundation, 2014

40. Saṃskṛta Bhāṣāśāstra mattu Sāhityacaritrè (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K; Ranga-natha Sharma, N; Siddhagangayya, H. K. Bangalore: Department of Textbooks, Government of Karnataka, 1993

41. Saṃskṛtakāvya (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Vidyuth Prakashana, 2003

42. Saṃskṛtasāhityadalli Śṛṅgārarasa (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krishnamoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2011

43. Sanskrit Learning through the Ages (Ed. Marulasiddhiah, G). Mysore: The Oriental Re-search Institute, 1970

44. Sāyaṇa’s Subhāṣitasudhānidhi (Ed. Krishnamoorthy, K). Dharwar: Karnatak Universi-ty, 1968

45. Some Thoughts on Indian Aesthetics and Literary Criticism. Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Prasaranga, University of Mysore, 1968

46. Śṛjanaśīlatè mattu Pāṇḍitya (Kannada). Krishnamoorthy, K. Bangalore: Dr. K. Krish-namoorthy Sanskrit Research Foundation, 2011

47. Studies in Indian Aesthetics and Criticism. Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: D.V.K. Murthy Publishers, 1979

48. The Dhvanyāloka and its Critics. Krishnamoorthy, K. Mysore: Kavyalaya Publishers, 1968

49. The Vakroktijīvita of Kuntaka (with English translation). Krishnamoorthy, K. Dharwar: Karnatak University, 1977

50. Vādirāja’s Yaśodharacarita (with Lakṣmaṇa’s commentary; edited with English trans-lation). Krishnamoorthy, K. Dharwar: Karnatak University, 1963

51. Yugayātrī Bhāratīya Saṃskṛti (vol. 2; Kannada). Mysore: University of Mysore, 1971