Krishnamoorthy has expounded on an English sonnet composed by Wilfred Owen using Indian literary principles.[1] His analysis of Thomas Gray’s famous poem Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard is fascinating:

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear;

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

A sahṛdaya would at once feel the depth of pathos in the situation as presented by the poet. The country churchyard is an ideal vibhāva or background for the rise of gloomy thoughts relating to death. He realizes that the poet is imaginatively going over the varied precious potentialities that death might have nipped in the bud; and sees at once how the analogies cited add to the crystallization of the mood of sorrow. In other words, the sahṛdaya would not hesitate to take it as a very telling example of karuṇa-rasa-dhvani with its beauty enhanced by the apt application of alaṅkāra and characterized by the quality of Sweetness and Perspicuity in style. The poet’s touch of originality is seen in inviting sympathy towards the common run of mankind in lieu of the usual heroes of history, and suggesting that there might be persons in the country-side more intrinsically worth than some recipients of honour at court. (Studies in Indian Aesthetics and Criticism, pp. 94–95)

* * *

Krishnamoorthy’s writings also touch upon some important aspects of comparative aesthetics. He finds a parallel to Ānandavardhana’s explanation of svataḥsaṃbhavī, kavi-prauḍhokti and kavinibaddhaprauḍhokti in one of T S Eliot’s essays titled Three Voices of Poetry.[2] According to him, a poet predominantly employs them in epic, lyric and drama, respectively.

Building on the findings of his predecessors, he showed striking parallels between Indian concepts such as rasa, sādhāraṇīkaraṇa etc. and ‘objective correlative,’ a concept popularized by T S Eliot.

He explains that the Indian distinction between bhāva and rasa bears a close resem-blance to ‘personal emotion’ and ‘art emotion’ as enunciated by T S Eliot.[3]

Kant formulated four principles to distinguish aesthetic judgement from other forms of judgement. He conceptualized four ‘moments’ that separate the beautiful from the scientific, moral and practical. The four moments are of disinterestedness, universality, finality and necessity. Krishnamoorthy posits that Abhinavagupta’s explanation of aesthetic experience includes all of these.[4]

In his considered opinion, the concept of anukīrtana as explained by Bharata and Abhinavagupta is a better form of Aristotle’s ‘mimesis.’[5]

Krishnamoorthy sees an echo of Aristotle’s conception of ‘catharsis’ in a verse from Bhaṭṭa Tauta’s Kāvyakautuka, a unique work that is now available only in fragments:

यथादर्शान्मलेनैव मलमेवोपहन्यते।

तथा रागावबोधेन पश्यतां शोध्यते मनः॥

Just as dust is used to clean up a rusty mirror, the mind of the critic is purified of passion through passion itself! (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 50)

* * *

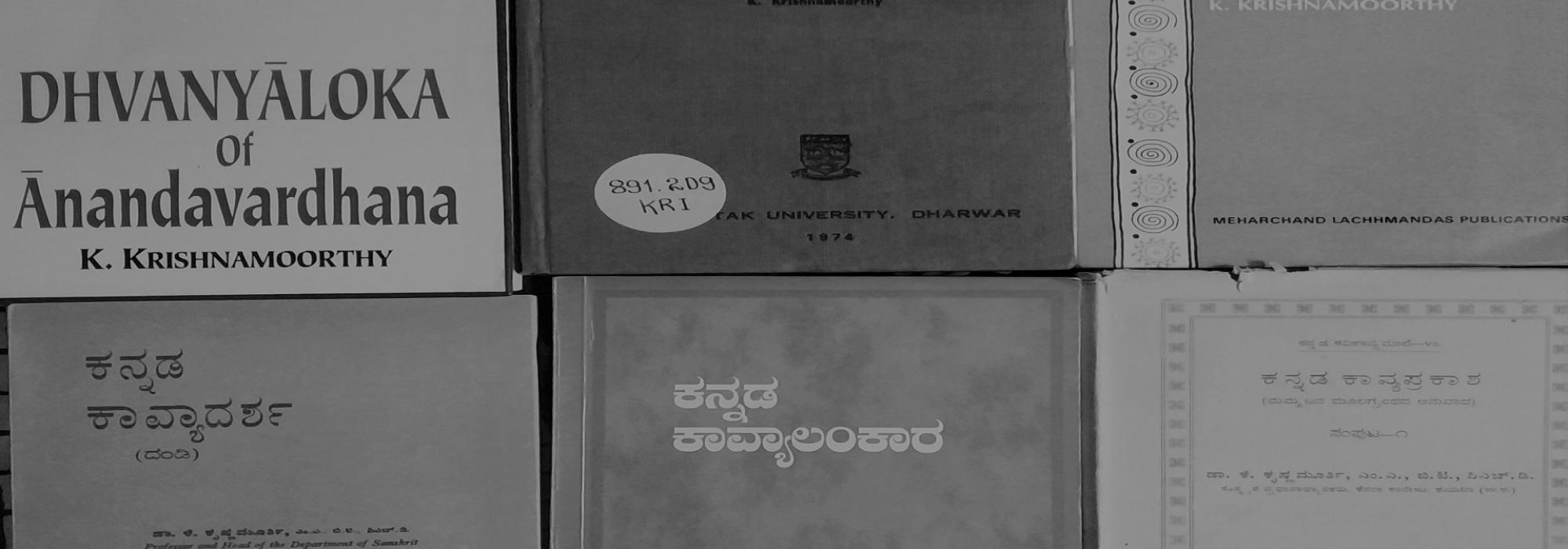

Krishnamoorthy is credited with preparing the critical edition of Dhvanyāloka, a text that marks the highest accomplishment of India in the field of aesthetics. Apart from writing numerous scholarly articles explaining and clarifying various aspects connected with the text, he authored a textbook in Kannada that serves as a most reliable introduction to poetic suggestion.

He conclusively established that Ānandavardhana is the author of both the kārikā and vṛtti portions of the text, taking on the likes of P V Kane, S K De and S P Bhattacharya.[6] The following are some of the arguments he presented: (1) Jayanta-bhaṭṭa, a strong opponent of dhvani, makes no difference between the kārikā and vṛtti portions. (2) In the fourth chapter of the text, kārikās and vṛttis are broken up in several places; this could not have been possible if the text were to have two authors. (3) Illustrative examples are of supreme significance to literary theory. “There can be a Sāṅkhyakārikā or even a Māṇḍūkyakārikā without examples; but not Dhvanikārikā.”

Krishnamoorthy edited and published Kuntaka’s Vakroktijīvita, another important text in Indian aesthetics. Before he published his edition, the text was available only in parts. He explained that this is a companion volume to Dhvanyāloka – Kuntaka describes the poetic process from the perspective of the poet while Ānandavardhana does the same from the perspective of the connoisseur. He drew attention to Kuntaka’s contribution as a literary critic by enlisting various instances of practical criticism embedded in Vakroktijīvita. One of his articles titled Kālidāsa in the Eyes of Kuntaka[7] is a major contribution to vakrokti studies.

Krishnamoorthy drew the attention of scholars for the first time to the pramāṇas or criteria in Indian aesthetics, preserved in ancient texts such as Nāṭyaśāstra and Vyaktiviveka.[8] Veda, loka and adhyātma are the pramāṇas. They denote, respectively, knowledge handed down through the tradition, the world around and one’s own experience. A correct understanding of these is central to art appreciation.

He established that Viśveśvara, the author of Camatkāracandrikā, is the first scholar to refer to the famous Upaniṣadic mantra raso vai saḥ in connection with aesthetic experience. (Basavaṇṇanavara Vacanamīmāṃsè, p. 28)

His monograph in Kannada titled Śṛjanaśīlatè mattu Pāṇḍitya and several English articles such as The Sanskrit Conception of a Poet and The Office of the Sanskrit Poet in Theory and Practice illustrate how genius and talent, imagination and erudition, inspiration and practice went hand in hand in India. Among other things, they include several savoury verses selected from a wide range of Sanskrit and Kannada works.

* * *

Krishnamoorthy’s books are strewn with extraordinary insights into various aspects of aesthetics. The following are a few samples:

What is abhinaya in theatre is varṇanā in poetry. (Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, p. 34)

Alaṅkāra, guṇa and rīti are concepts that help in the appreciation of standalone verses and small segments of poetry. Rasa and dhvani are concepts that aid in the analysis of whole works such as poems, plays and epics. (Bhāratīya Kāvyamīmāṃsè Tattva mattu Prayoga, p. 8; translation mine)

Connoisseurs should never forget the distinction between poetic suggestion and riddle. Prahelikā often masquerades as vastudhvani. We should take care to see it for what it is. If we are able to easily imagine the idea suggested by a verse, it is an illustration of vastudhvani; if we experience difficulty, it is an illustration of prahelikā. (Bhāratīya Kāvyamīmāṃsè Tattva mattu Prayoga, p. 48; translation mine)

On defining poetry:

Such are the fundamental key-terms in Indian Aesthetics—alaṅkāra, guṇa, bhāva, rasa, rīti, vṛtti—which are all inter-involved since each explains an aspect of beauty in the poetic art and our idea of overall beauty would remain but partial and incomplete if we ignore any of these aspects. That is why almost all attempts at a definition of literature have become instances of so many failures in India as well as in the West. (Indian Literary Theories, p. 15)

It is in the very nature of poetry that it eludes an overall definition, though one cannot fail to recognize it when one finds it.[9] (Indian Literary Theories, p. 39)__________________________

[1] Indian Literary Theories, pp. 60–64

[2] Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, pp. 274–80

[3] The Dhvanyāloka and its Critics, p. 313

[4] The Dhvanyāloka and its Critics, pp. 315–17

[5] Alaṅkāraśāstre Kāvyavaividhyavādavimarśaḥ (Sanskrit), pp. 39–45

[6] The Dhvanyāloka and its Critics, pp. 46–90; Indian Literary Theories, pp. 183–90

[7] Indian Literary Theories, pp. 222–30

[8] Indian Literary Theories, pp. 131–35

[9] Ref: Krishnamoorthy’s own definition of poetry:

प्रतिभाभाविताशेषवर्णनानिपुणः कविः।

तस्य कर्म भवेत्काव्यं रसभावनिरन्तरम्॥ (Alaṅkāraśāstre Kāvyavaividhyavādavimarśaḥ, p. 3)