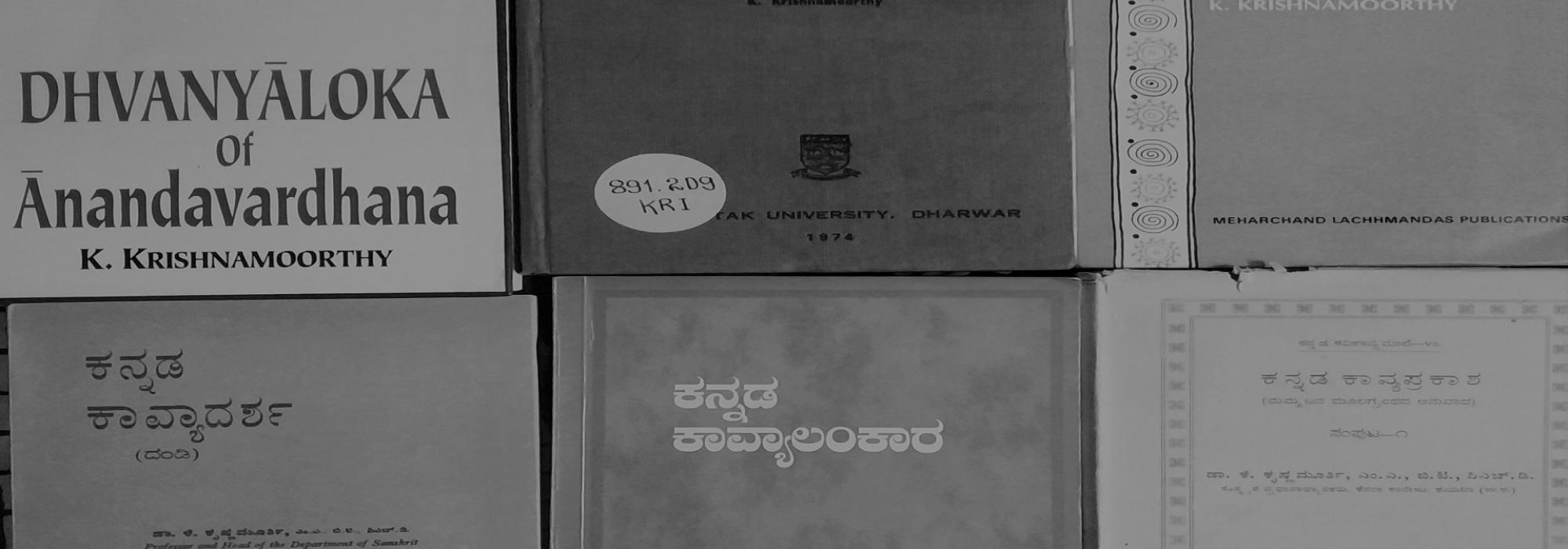

Translations form a major part of Krishnamoorthy’s oeuvre. His English translations of Sanskrit works include Dhvanyāloka, commentary by an anonymous author on the first chapter of Locana, Vakroktijīvita, Yaśodharacarita, Kavikaumudī and a few sections in Ancient Indian Literature (vol. 2) published by Sahitya Akademi.

His Kannada translations of Sanskrit classics include Pratimānāṭaka, Yajñaphala, Svapnavāsavadatta, Dūtaghaṭotkaca, Karṇabhāra, Madhyamavyāyoga, Abhijñānaśākuntala, Mālavikāgnimitra, Mṛcchakaṭika, Uttararāmacarita, Āścaryacūḍāmaṇi (plays); Mudrārākṣasakathāsāra and the first six cantos of Kirātārjunīya (poems); Kāvyālaṅkāra, Kāvyādarśa, Kāvyālaṅkārasūtravṛtti, Dhvanyāloka, Kāvyamīmāṃsā, Aucityavicāracarcā, Kavikaṇṭhābharaṇa and Kāvyaprakāśa (treatises on poetics).

His Kannada renderings of the works of Bhāmaha, Ānandavardhana and Mammaṭa are classics in their own right. Krishnamoorthy places the texts in their historical backdrop, discusses ancillary concepts related to them, cites the opinions of several commentators, profusely draws parallels from Western criticism and presents an up-to-date summary of the views of modern scholars on the subject. If a person with a perceptive head and sensitive heart carefully studies just the introduction and footnotes of these works, he will surely become a scholar of Indian aesthetics.

Krishnamoorthy also translated into Kannada James Hilton’s English novel Lost Horizon as Lupta Diganta, one volume of P V Kane’s monumental History of Dharmaśāstra, one volume of M Winternitz’s A History of Indian Literature, Bankim Chandra’s Bengali classic Śrīkṛṣṇacaritra, several introductions and articles in The History and Culture of the Indian People and The Cultural Heritage of India.

Whether translating from Sanskrit into English or Kannada, Krishnamoorthy achieves a high degree of readability while staying close to the original. He adheres to the natural idiom of the language and does justice to the tone of the text – be it a play, a discursive essay or a treatise on aesthetics. In Kannada, he translates verse as verse, mostly sticking to the metrical form of the original. Depending on the structure of the original and the purpose of the translation, he chooses time-honoured metres such as kanda and vṛttas or adopts a mātrā measure. Let me give a few examples of his translation:

रविसङ्क्रान्तसौभाग्यस्तुषारावृतमण्डलः।

निःश्वासान्ध इवादर्शश्चन्द्रमा न प्रकाशते॥(Dhvanyāloka of Ānandavardhana, 2.1; p. 40)

All the charm to the sun hath fled

And the orb is hid in snow;

Like a mirror by breath blinded

The moon now does not glow (Dhvanyāloka of Ānandavardhana, 2.1; p. 41)

मानिनीजनविलोचनपाता-

नुष्णबाष्पकलुषाननुगृह्णन्।

मन्दमन्दमुदितः प्रययौ खं

भीतभीत इव शीतमयूखः॥ (The Vakroktijīvita of Kuntaka, 1.7, p. 9)

Slowly and softly the moon does rise

As if he were gripped with fear,

Exposed to the burning glances of damsels

Bathed in hot and streaming tears (The Vakroktijīvita of Kuntaka, 1.7, p. 295)

दारिद्र्याद्ध्रियमेति तत्परिगतः प्रभ्रश्यते तेजसो

निस्तेजाः परिभूयते परिभवान्निर्वेदमापद्यते।

निर्विण्णः शुचमेति शोकविहतो बुद्ध्या परित्यज्यते

निर्बुद्धिः क्षयमेत्यहो निधनता सर्वापदामास्पदम्॥ (Mṛcchakaṭika, 1.14)

ದಾರಿದ್ರ್ಯದಿಂ ಲಜ್ಜೆ, ಲಜ್ಜೆಯಿಂ ಕಳೆಯಳಿವು

ಕಳೆಯಳಿಯಲವಮಾನ ಬಿಡದೆ ಬಹುದು;

ಅವಮಾನದಿಂ ಖೇದ, ಖೇದದಿಂ ಕಟುಶೋಕ,

ಕಟುಶೋಕಮಾವರಿಸೆ ಮತಿ ಪೋಪುದು;

ಮತಿ ಪೋಗಲದೆ ನಾಶವೀ ತೆರದೆ ಬಡತನವು

ಆಪತ್ತುಗಳಿಗೆಲ್ಲ ಬೀಡಪ್ಪುದು (Kannaḍa Mṛcchakaṭika, p. 7)

ततोऽरुणपरिस्पन्दमन्दीकृतवपुः शशी।

दध्रे कामपरिक्षामकामिनीगण्डपाण्डुताम्॥

ಕಿರಣಾರುಣಗಣಮೇರ--

ಲ್ಕುರುಬಿಂಬಂ ಮಂದಮಂದಮೆನಿಸಲ್ ಚಂದ್ರಂ

ವಿರಹದ ಬಿಸುಪಿಂ ಬಳಲುವ

ತರುಣಿಯ ಮೊಗದೊಳ್ಪಿನಂತೆ ಬೆಳ್ಪಿಂದೆಸೆದಂ (Kannaḍa Kāvyaprakāśa, p. 137)

पश्चादङ्घ्री प्रसार्य त्रिकनतिविततं द्राघयित्वाङ्गमुच्चै-

रासज्याभुग्नकण्ठो मुखमुरसि सटां धूलिधूम्रां विधूय।

घासग्रासाभिलाषादनवरतचलत्प्रोथतुण्डस्तुरङ्गो

मन्दं शब्दायमानो विलिखति शयनादुत्थितः क्ष्मां खुरेण॥

ಬಿಡಿಸುತ್ತುಂ ಪೂರ್ವಪಾದದ್ವಯಮನವನತಸ್ಕಂಧದಿಂದಂಗಮುದ್ದಂ

ನಡೆ ಕಾಣಲ್, ಬಾಗೆ ಕಂಠಂ, ಮೊಗಮಿರಲೆದೆಯೊಳ್, ಕೇಸರಂ ಧೂಳಿಧೂಮ್ರಂ

ನಡುಗುತ್ತುಂ ಪಾರೆ, ಪುಲ್ಲಂ ಮೆಲುವ ಬಯಕೆಯಿಂ ಬಾಯನಳ್ಳಾಡಿಸುತ್ತುಂ

ನಿಡಿದುಂ ಕೂಗುತ್ತಮಶ್ವಂ ಬರೆವುದು ಗೊರಸಿಂ ಭೂಮಿಯಂ ನಿದ್ರೆ ಜಾರಲ್ (Kannaḍa Kāvyaprakāśa, p. 236)

* * *

At the beginning and end of his essays, Krishnamoorthy usually quotes verses that are rare and beautiful. These verses reveal his wide reading and impeccable aesthetic taste. H M Nayak, the well-known Kannada littérateur, has recorded a nice anecdote, which I would like to quote here.

Krishnamoorthy was put up at Kumta while working on the translation of Bhāmaha’s Kāvyālaṅkāra. He had finished writing the introduction but was looking for an apt verse to conclude the essay. It was raining when he went to college that morning. No sooner had he reached the library than an old piece of paper that had fallen from a book stuck to his wet shoes. Krishnamoorthy picked it up, read and found the perfect verse he was looking for (Saṃpradāna, pp. 141C–141D):

कस्यचिदेव कदाचि-

द्दयया विषयं सरस्वती विदुषः।

घटयति कमपि तमन्यो

व्रजति जनो येन वैदग्धीम्॥(Daśarūpaka, 1.3)

Someone, sometime, endowed with Sarasvatī’s grace, understands a con-cept; realization dawns on him. Armed with this, someone else becomes a scholar.

Krishnamoorthy believed that the sayings of past masters supply strength to our feeble words. A well-crafted verse with a telling imagery can easily accomplish what pages and pages of logical exposition cannot.

He cites the verses of poets and scholars such as Ratnaśrījñāna, Abhinavagupta, Bilhaṇa, Maṅkha, Dhanañjaya, Narendraprabha-sūrī, Appayya-dīkṣita, Vedānta-deśika, Bhaṭṭoji-dīkṣita, Nīlakaṇṭha-dīkṣita, Siṃhabhūpāla and Śrīkṛṣṇa-brahmatantra-svāmī.

The following are a few representative examples:

चिरन्तनो वा कविरद्य वा स्फुटं

गुणोत्तरं वाक्यमुपास्यते बुधैः।

तरोः पुराणस्य नवस्य वा फलं

निरस्तशङ्कं मधुरं निषेव्यते॥ (Ratnaśrī; Aspects of Poetic Language, p. 34)

वाणी पङ्करुहासनस्य गृहिणीत्यास्थायि मौनव्रतं

लक्ष्मीः सागरशायिनः प्रियतमेत्यग्राहि भिक्षाटनम्।

इत्थं स्वामिनिषिद्धसेवकवधूसम्भोगबीभत्सया

पञ्चासेविषत त्वया धृतिदयादान्तिक्षमामुक्तयः॥ (Bilhaṇastava, 19; Indian Literary Theories, p. 30)

केचिद्विस्तरदुस्तरास्तदितरे सङ्क्षेपदुर्लक्षणाः

सन्त्यन्ये सकलाभिधेयविकलाः क्लेशावसेयाः परे।

इत्थं काव्यरहस्यनिर्णयबहिर्भूतैः प्रभूतैरपि

ग्रन्थैः श्रोत्रगतैः कदर्थितमिदं कामं मदीयं मनः॥ (Alaṅkāramahodadhi; Aspects of Poetic Language, pp. 67–8)

अप्पय्यदीक्षितेन्द्रा-

नशेषविद्यागुरूनहं वन्दे।

यत्कृतिबोधाबोधौ

विद्वदविद्वद्विभाजकोपाधी॥ (Tantrasiddhāntadīpikā; Alaṅkāraśāstrakkè Appayyadīkṣitara Koḍugè, p. 2)

नेदानीन्तनदीपिका किमु तमःसङ्घातमुन्मूलये-

ज्ज्योत्स्ना किं न चकोरपारणकृते तत्कालसंशोभिनी।

बालः किं कमलाकरं दिनमणिर्नोल्लसयेदञ्जसा

तत् सम्प्रत्यपि मादृशामपि वचः स्यादेव सत्प्रीतये॥ (Rasārṇavasudhākara; New Bearings of Indian Literary Theory and Criticism, p. 30)

अन्धीभूय गुणागुणेषु तरवो वातावधूता इव

श्लाघन्ते यदि साहितीं रसवतीमज्ञास्ततः किं फलम्।

जानन् व्यङ्ग्यचमत्कृती रसगतीरर्थौचितीरादरा-

दन्तःशर्म यदश्नुते सहृदयः सा जीवनाडी कवेः॥ (Alaṅkāramaṇihāra; Indian Literary Theories, p. 32)

Apart from these, he quotes verses from epigraphs, unpublished manuscripts and works on various śāstras.

* * *

Among his original works in English, the following are the most significant: The Dhvanyāloka and its Critics, Essays in Sanskrit Criticism, Studies in Indian Aesthetics and Criticism, Some Thoughts on Indian Aesthetics and Literary Criticism and Indian Literary Theories: A Reappraisal.

Krishnamoorthy edited a few chapters of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra published from the Gaekwad Oriental Series, Baroda. He wrote monographs on Bāṇa and Kālidāsa for Sahitya Akademi. In the evening of his life, he worked on A Critical Inventory of Rāmāyaṇa Studies.

He was not a mere theorist. He undertook practical criticism whenever the opportunity presented itself. He analyzed poetry in Sanskrit, Kannada and English in the light of fundamental tenets of Sanskrit aesthetics such as rasa, dhvani, aucitya and vakrokti.

As far as Sanskrit poetry is concerned, he wrote two wonderful papers on the figures of speech in Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa and Kumāradāsa’s Jānakīharaṇa, covering between these all turns of expression that poets are likely to employ in sublime and ornate epics. His analysis of a famous verse in the Dhvanyāloka—anurāgavatī sandhyā...—is a landmark in Sanskrit practical criticism. He has unraveled the viśvarūpa of alaṅkāras by identifying as many as seven figures of sense in this small verse: śliṣṭa-rūpaka, samāsokti, viṣama, viśeṣokti, vibhāvanā, ākṣepa and nidarśana. Space does not permit more details.

Krishnamoorthy has analyzed several poems using dhvani in Kannada. In Ānandavardhanana Kāvyamīmāṃsè, he has chosen apt examples for various types of poetic suggestion from ancient and modern Kannada works. This is a remarkable achievement. He has also analyzed the vacanas of Basavanna using the tenets of Indian aesthetics. His article on the figures of speech in Karṇāṭa-bhārata-kathāmañjarī is unique. Its title is indicative of Krishnamoorthy’s keen literary sensibility: Kumāravyāsanalli Vidyāpariṇatara Alaṅkāra. Students of Kannada literature will immediate recognize vidyāpariṇatara alaṅkāra as a phrase that appears in the very poem that the essay sets out to analyze. He wrote a full-length book on the science of criticism in Kannada, titled Kannaḍadalli Kāvyatattva. He also edited Kavirājamārga, a seminal work on poetics and grammar in Kannada.