yadihAsti tadanyatra yannEhAsti na tat kvacit || (Adi Parva: 56:33)

That which exists in the Mahabharata exists everywhere in the world.

That which is not in the Mahabharata does not exist anywhere else.

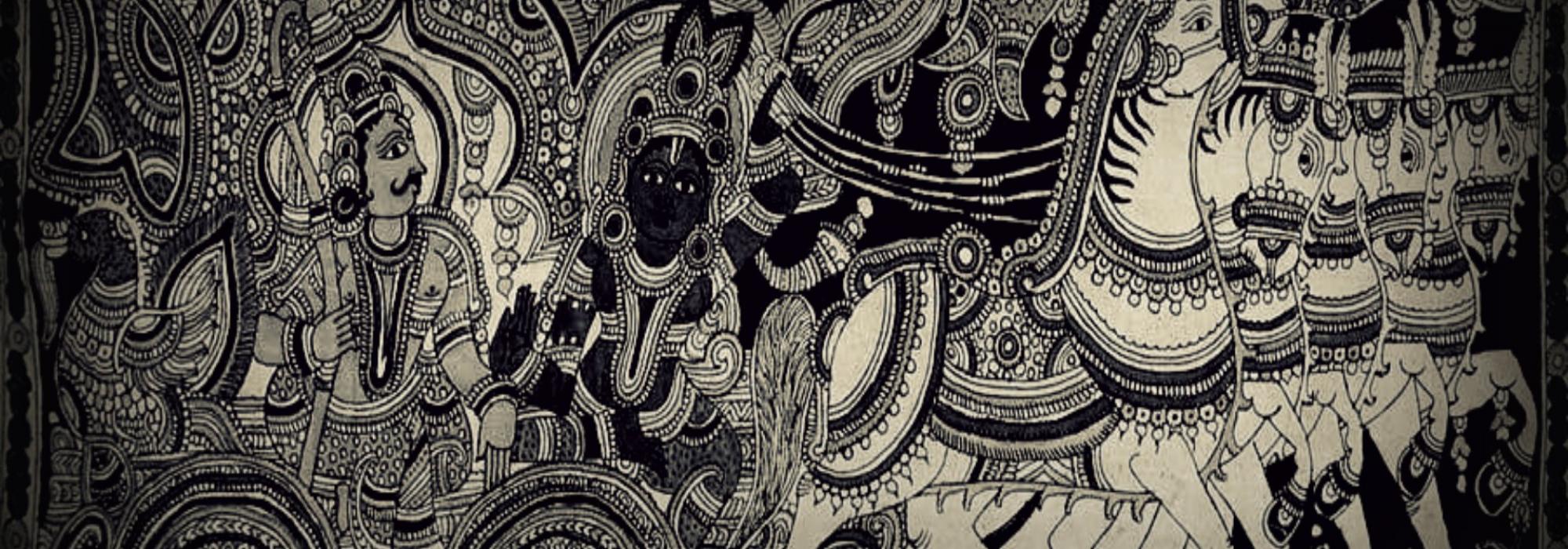

Such laudatory exclamations, and the eulogies of the greatness of Bhagavan Veda Vyasa, the architect of Indian culture and civilization, are plentiful. Even if we regard the Mahabharata merely as a work of literature, it continues to stand as an unparalleled feat.

“Dharma,” the edifice of Indian culture is a conception that is all-pervading and has universal scope. The fact that the Mahabharata is a primary source of Dharma is indisputable. In this backdrop, the craft of the composition of the Mahabharata, its intended message and the multilayered meaning embedded therein are definitely worthy of deep contemplation.

Even when we examine the canopy of its plot and the various twists in it, there is no dearth for the sheer literary enjoyment it affords us. That its story is also a record of a protracted era of the history of our country is a fact. In spite of this, it cannot be said that the Mahabharata—which stands on the summit in the history of world literature—was composed merely for the preeminence of its story.

There is yet another aspect to this. Because there is an expectation that an encyclopedic work like the Mahabharata should also be self-complete, answers to philosophical questions should also emanate from within the work itself. It is worth examining as to the extent to which this objective has been fulfilled. “dhAraNAt dharma ityAhuh” – Dharma is that which sustains the world (Karna Parva: 69:58) – is one of the definitions of Dharma. Therefore, the question must be posed: does the Mahabharata reflect this eternal substance of Dharma? Was Dharma established as a consequence of the enormous upheaval that takes place in it? Was the destruction of Adharma—which is necessary for peace and order in the world—achieved?

Numerous such questions arise. If our Shraddha (deep, devoted and unwavering conviction) needs to be reaffirmed, the relationship between cause and effect must become clear at the level of the intellect—indeed, one cannot ignore the school of thought that postulates this intellectual argument.

Structure of the Work

Those who seek to explain the meaning of the Mahabharata purely from the standpoint of language and style should understand a vital point—decades before it took the textual form, the Mahabharata had attained pervasive popularity for hundreds of years as an oral (literary) tradition. Additionally, both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata were inextricable parts of an entire peoples’ historical memory, which was kept alive at the level of their active consciousness. Even those traditional scholars who had accepted the theory of the three-phased development of the Mahabharata did not endeavor to classify the work on the basis of this theory. Indeed, numerous portions of the work which are deemed to be interpolations based on manuscript evidence are not only ancient but have become inseparably intertwined with the original.

The Mahabharata is not a work that is tightly bound within the confines of space and time. It is true that it contains historical and geographic details. Bhagavan Veda Vyasa has used these and other episodes like war merely as instruments for establishing and propounding the eternal value called Dharma. The central theme of the Mahabharata is an exploration of how an individual can elevate himself in a world full of paths and sects that compete with one another to entice him. Given this, the answers to questions and conflicts regarding Dharma arising in our mind will only be found at the level of philosophy located beyond the awning of the story.

Countless generations throughout the centuries have revered the Mahabharata not merely for its story. Indeed, almost everyone has heard and read its story innumerable times. In spite of this, they want to listen to this familiar story repeatedly with the anticipation of finding some new message, insight or light—from the prior experience of having seen something new each time they have heard it anew. The work has the innate capacity of giving different experiences at different stages of life: in childhood, youth, middle age and dotage. The work remains the same; the person grasping it varies.

Dharma: The Establisher of Balance and Order

The feeling that arises in our mind after we finish reading this work of one lakh verses is this: the Mahabharata is not over, it is still continuing. The singular message that resonates and reaffirms itself throughout the work is this: only Dharma is deserving of becoming the goal of one’s life.

nityO dharmah sukhadukhE tvanityE

jIvO nityO hEturasya tvanityah || (swargArohaNa Parva)

In summary: Dharma is the most exalted value because it alone is capable of striking a fine balance between the eternal and the transient. We need to bear in mind a fundamental point when we contemplate on this – the entire Mahabharata as one event and the work itself are self-complete. They are their own yardsticks. All the people and episodes in the work are immersed in the ocean of a history whose depth is unfathomable. No matter how diametrically opposite they all appear, it is impossible to separate one from the other.

We are aware of the well-known stories of the Devas and the Asuras occurring in the Vedas. The lore that begins in this fashion culminates in the highpoint of the Upanishads as follows:

adhyAtmayOgAdhigamEna dEvam

matvA dhIrO harsHashOkam jahAti || (Kathopanishad: II:12)

The Cascade of the Upanishadic Insight

Perhaps for the first time in the world, the Upanishads performed the lofty task of elevating our knowledge of the physical world in an immemorial fashion. In the process of the development of the Upanishad Darshana (philosophy), the Puranic literature with its conceptions of Devas and Asuras can be regarded as an intermediate stage. Elements regarded as otherworldly are in reality, different states of our inner life—this is the invaluable and the profoundest Darshana of the Upanishads. When we examine the Mahabharata in this Upanishadic backdrop, it becomes easy to grasp its philosophic ideal.

Thus, the distilled meaning of the Mahabharata is this: the noble impulses that lie in an unawakened state within all of us must be awakened with conscious effort. It is precisely due to the lack of the knowledge of such cultural subtleties on the part of the mere textual scholars of the West that their analyses sound worthless and useless to us. A profound literature like the Mahabharata must essentially be understood by being firmly grounded in the Sanatana Dharma of Bharata. Indeed, we have the word of Sri Krishna himself who says that only a few in a thousand will have the ability to perceive the grandeur of Reality (Bhagavad Gita: 7:3)

Incarnations of the Divine, human attempts at spiritual elevation—the intuitive understanding of these two foundational pillars are present in our people even to this day. It is precisely this intuitive awareness that will help resolve the confusions or doubts that are born in the mind. The works of Sastra have simply codified the experience-based knowledge and analyses of the nature of the world.

To be continued