Let us now examine some of the salient features of Poetics expounded by Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi.

4.2. Poet and Poetry

The Indian aesthetic tradition holds rasa as the raison d’être of poetry. However, it sees no difference between the joy and education that rasa provides.[1] Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi agrees with this view but considers education as an additional benefit derived out of enjoying rasa. Using a memorable example, it says: “Deriving upadeśa from poetry, which is primarily meant for enjoyment, is like being paid to savour sugarcane”–

यथा वेतनवित्तस्य लाभः पुण्ड्रेक्षुभक्षिणाम्।

तथोपदेशलाभोऽपि रसास्वादविधायिनाम्॥ 1.31

Among the prerequisites of a poet Sāyaṇācārya counts only śakti (pratibhā) and vyutpatti. Unlike Mammaṭa he subsumes abhyāsa under vyutpatti. He holds śakti as the primary prerequisite—an innate talent that is the very seed of poetry—without which a person cannot become a poet however learned s/he might be:

शक्तिः कवित्वबीजं हि प्राक्तनी कापि संस्क्रिया।

यया विना न प्रसरेत्काव्यं शिक्षावतामपि॥ 1.35

He further states: “If an untalented person attempts to compose poetry spurred on by his scholarship, his work will surely be a laughing-stock”:

व्युत्पत्तिगौरवबलाद्यदि किञ्चित्कथञ्चन।

प्रसारितं परं तच्च हास्यमेव न संशयः॥1.36

In the next verse the author describes pratibhā as “the bosom-friend of daivī vāk embodied in the Vedas”:

पराया जीवितसखीं देव्या वाचस्त्रिधातनोः॥ 1.37

This tells us that Sāyaṇācārya had the highest respect for pratibhā. The image is unique and appropriate, for the person who created it is the author of commentaries on all the Vedas!

Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi accepts three kinds of vyutpatti: śāstra-vṛtta-jñāna, loka-vṛtta-jñāna and abhyāsa. It describes abhyāsa as the training a student receives from masters of the art, and extends its meaning to the constant and dedicated practise of versification:

काव्यं कर्तुं विवेक्तुं च ये जानन्ति त एव हि।

काव्यज्ञास्तैस्तदभ्यस्येदुपदिष्टेन वर्त्मना॥ 1.57

उपदिष्टेन काव्यज्ञैरेवंरूपेण वर्त्मना।

मुहुर्मुहुः समभ्यस्येत्तैः समं काव्यनिर्मितिम्॥ 1.58

Quoting the views of Vāmana and Ānandavardhana, Sāyaṇācārya outlines some important tenets of structure—such as śabda-pāka and harmony between sound and sense—that a poet must bear in mind.

The author lays special emphasis on loka-vṛtta-jñāna or knowledge of worldly affairs, bereft of which a poet becomes a butt of ridicule like the naïve Ṛṣyaśṛṅga:

अज्ञातलोकवृत्तो यः शास्त्रकाव्यविदप्यसौ।

ऋष्यशृङ्ग इवाशेषैर्घुष्यते मुग्धसंसदि॥ 1.42

We know that Sāyaṇācārya was a minister who held his thumb over the pulse of worldly affairs, and thus it is small wonder he emphasizes worldly knowledge.

The author advises poets to study śāstras, purāṇas and kāvyas individually, devoting exclusive attention to each, and cautions that knowledge of one does not lead to knowledge of the others:

अन्या हि गतिरश्वस्य गतिरन्या खरोष्ट्रयोः।

मदक्लिन्नकपोलस्य गतिरन्या हि दन्तिनः॥ 1.52

लोकशास्त्रपुराणानां रीतयो हि पृथक्पृथक्।

रीतिरन्यैव काव्यानां लोकोत्तरपदस्पृशाम्॥ 1.53

Following the lead of Kṣemendra, Sāyaṇācārya exhorts budding poets to study the works of master poets such as Kālidāsa:

लोकशास्त्रविशेषज्ञः काव्यनिर्माणकौतुकी।

काव्यानि कालिदासादेः सततं परिशीलयेत्॥ 1.50

तस्मादालोचिताशेषलोकशास्त्रेण धीमता।

कर्तव्यं कालिदासादेः काव्यानां परिशीलनम्॥ 1.55

He places Kālidāsa’s compositions on par with the Vedas and recommends them to neophytes seeking instruction in their craft:

इतः कविभ्यः कालिदासस्य वैशिष्ट्यं तद्वाक्यानां वेदवत्प्रामाण्यं च भट्टाचार्यपादैः प्रतिपादितम्। यथा—

“कवयः कालिदासाद्याः कवयो वयमप्यमी।

पर्वते परमाणौ च पदार्थत्वं व्यवस्थितम्॥” इति।

Drawing from his extensive first-hand knowledge of the Vedas, Sāyaṇācārya cites several mantras and assigns the highest place to the poet:

कवीनां लोकोत्तरत्वं वेदेऽपि विशिष्टदेवतावाचकत्वेन “अनन्तमव्ययं कविम्”, “कविं कवीनामुपमश्रवस्तमम्”, “कविं सम्राजमतिथिं जनानाम्” इत्यादौ प्रतिपादितत्वात्। व्यासवाल्मीकिप्रभृतिषु ब्रह्मणो मुखेन प्रतिपादनात् क्रान्तदर्शिनां कवीनां लोकोत्तरत्वम्।

Despite being a devout adherent of the Vedas and śāstras, the author upholds the autonomy of poetry by enlisting the unique gifts it offers:

रसभावगुणौचित्यघटनालङ्क्रियादयः।

काव्यादन्यत्र दृश्यन्ते कुत्र वा वेदशास्त्रयोः॥ 1.54

Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi defines poetry in the following manner:

लोकोत्तरगतावर्णवर्णनानिपुणः कविः।

तस्य कर्म भवेत्काव्यं रसभावनिरन्तरम्॥[2] 1.60

It is difficult to grasp the exact import of this cryptic kārikā. Taking the help of the ensuing vṛtti, we attempt to explain: A poet is one who is endowed with the talent and skill to create über-worldly, unblemished descriptions. His creation, poetry, is a composition laden with rasa. The term ‘rasa-bhāva-nirantara’ refers to rasādi as propounded by Ānandavardhana. It connotes a complex of ‘personal feelings’ and ‘art emotions,’ semblances of these, the advent and decline of personal feelings, their segue from one to another and ultimate admixture – all evoked through poetic suggestion. Further, the term ‘kāvya’ means the inseparable compound of form (śabda) and content (artha). Aestheticians such as Bhāmaha, Vāmana, Kuntaka and Bhaṭṭa-nāyaka posit different reasons for the uniqueness of such kāvya – alaṅkāra (figures of speech), rīti (style), vakrokti (oblique expression) and bhoga-kṛttva (aesthetic relish).

Sāyaṇācārya uses the template set by Ruyyaka at the beginning of Alaṅkāra-sarvasva in drawing up a conspectus of Alaṅkāra-śāstra that had developed till his time.[3] He devotedly follows the stand of Ānandavardhana and Abhinavagupta. (He addresses these savants in the plural, along with the honorific Ācārya, but names all other scholars in the singular.) Further, he justifies and adheres to Mammaṭa’s definition of poetry.[4]

4.3. Guṇa and Doṣa

Sāyaṇācārya sees a direct connection between guṇa and rasa by alluding to qualities such as śaurya that reside in the human soul:

शौर्यादय इवात्मानं ये धर्मा अङ्गिनं रसम्।

उत्कर्षयन्ति नियतस्थितयस्ते गुणा इह॥ 1.111

नयन्ति नित्यमुत्कर्षं समवायाद्रसं गुणाः।

शौर्यादय इवात्मानं शरीरेषु शरीरिणाम्॥ 1.113

He clearly upholds the rasa-dharmatva of guṇas and denounces those who limit their influence to śabdārtha-dharmatva –

इत्थं रसैकधर्मत्वं गुणानामुपपादितम्।

भ्रान्त्यैव केवलं प्राहुरज्ञाः शब्दार्थधर्मताम्॥ 1.115

Further, he says guṇas are inherent in and inseparable from the body of poetry (samavāya, 1.113) and contrasts them with alaṅkāras, which he holds are appurtenances separable from the body (saṃyoga, 1.114).

Following Bhāmaha, Ānandavardhana, Mammaṭa and Bhaṭṭa-gopāla, Sāyaṇācārya accepts only three guṇas: mādhurya, ojas and prasāda –

माधुर्यौजःप्रसादाख्यास्त्रय एव गुणा इह॥ 1.122आ

He follows Mammaṭa closely in jettisoning the ten guṇas pertaining to śabda and artha as propounded by Vāmana. He gives the following reasons for explaining these away: (1) some can be subsumed under mādhurya, ojas and prasāda; (2) some are not guṇas per se but are only the absence of doṣas; (3) some are demonstrably not guṇas and can even be considered doṣas –

अन्ये ये वामनाद्युक्ता अत्रैवान्तर्भवन्ति ते।

अनन्तर्भाविनो दोषत्यागाद्दोषाश्च संश्रिताः॥ 1.126

Sāyaṇācārya’s definitions of mādhurya, ojas and prasāda bear a close resemblance to Mammaṭa’s statements. He says:

Mādhurya is the quality that melts the mind; we experience it predominantly in śṛṅgāra and come under its spell in karuṇa, vipralambha and śānta in the ascending order:

आनन्दकृत्त्वं माधुर्यं शृङ्गारे द्रावयन्मनः।

करुणे विप्रलम्भे तच्छान्ते चाधिक्यवत्क्रमात्॥ 1.123

Ojas is the quality that expands the mind by account of its brilliance. We experience it mainly in vīra, bībhatsa and raudra in the ascending order:

ओजो दीप्त्यात्मविस्तारकारणं समुदाहृतम्।

वीरबीभत्सरौद्रेषु क्रमेणैतत्प्रकर्षति॥ 1.124

Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi echoes Ekāvalī (5.5) when it says the effect of ojas is starkly heightened in the depiction of bhayānaka –

किञ्चिन्मग्नमनोवृत्तिस्वभावेऽपि भयानके।

दीप्तत्वेन विभावस्य भजत्योजः परां भुवम्॥

Prasāda is the quality that pervades the mind instantaneously; it is like fire that consumes a dry piece of wood; it manifests equally well in all rasas (Ekāvalī, 5.6) –

यश्चित्तं व्यश्नुतेऽह्नाय शुष्केन्धनमिवानलः।

स प्रसादो गुणः सर्वरससाधारणस्थितिः॥

Sāyaṇācārya holds that rīti / saṅghaṭanā depends on and varies with guṇas. He enlists various letters of the Sanskrit alphabet that are conducive to the three guṇas; he even tailors them to different rasas. Because he believes guṇas are evoked by suitable letters, Sāyaṇācārya considers it wrong to attribute them to either śabda or artha exclusively. Interestingly, he reserves a huge chunk of the text, quite disproportional to the treatment of other concepts, to dismiss the views of Vāmana (1.122–157).

Coming to doṣa, Sāyaṇācārya defines it as ‘mukhyārtha-vyāhati’ – anything that obstructs or obfuscates rasa:

मुख्यार्थव्याहतिर्दोषो रसो मुख्यस्तदाश्रयात्। 1.110

As it is a factor detrimental to the delineation of rasa, doṣa relates only to it and not any other concept. In holding this view Sāyaṇācārya is indebted to Mammaṭa (Kāvya-prakāśa, 7.1).

Following Kāvyādarśa (1.7) Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi says, “Even a small blemish can mar the quality of poetry, just like a tiny leprous spot is enough to sully the human body” (1.118).

Although the concept of doṣas is not fully worked out by Sāyaṇācārya, we gather that he accepts four main kinds (1.110 vrtti) –

- Śabda-doṣa such as cyuta-saṃskāra

- Vākya-doṣa such as pratikūla-varṇatva

- Ubhaya-doṣa such as śruti-kaṭu

- Rasa-doṣa such as sva-śabda-vācyatva

4.4. Alaṅkāra

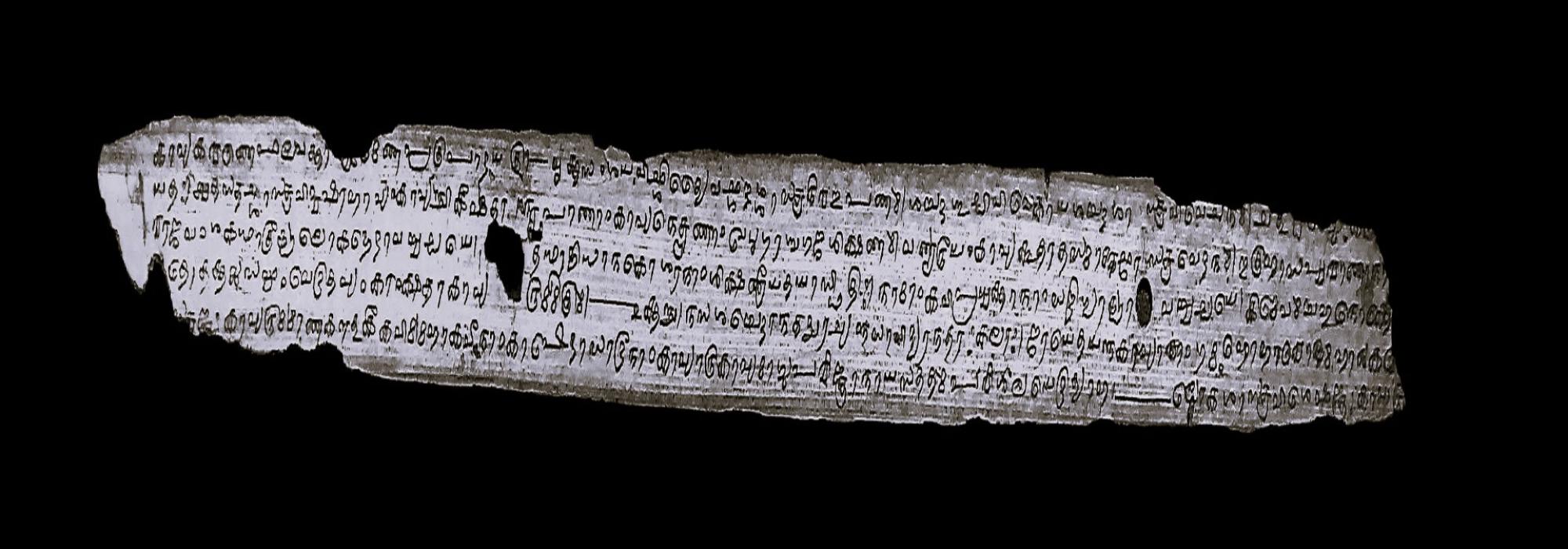

Examining the compositional structure of Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi we gather that its third chapter is devoted to the concept of alaṅkāras. Since this chapter is available only as a fragment, we cannot get a complete picture of Sāyaṇācārya’s treatment of alaṅkāras. He seems to have followed Mammaṭa and his commentator Bhaṭṭa-gopāla in elucidating this poetic concept. In fact, the third chapter opens with a lengthy quotation from Sāhitya-cūḍāmaṇi, Bhaṭṭa-gopāla’s commentary on Kāvya-prakāśa.

We have noted in the discussion on guṇa that Sāyaṇācārya counts alaṅkāras as external ornaments that beautify the body of poetry. The actual verse is:

ये त्वङ्गभूतशब्दार्थद्वारा तं सन्तमेकदा।

अलङ्कुर्वन्त्यलङ्कारा हाराद्या इव ते पुनः॥ 1.112

The text includes alaṅkāras under the citra variety of poetry in which the suggested meaning is not distinct:

तस्यास्फुटत्वेऽलङ्कारप्राधान्ये काव्यमिष्यते।

चित्रशब्दार्थविषयमधमं चित्रमित्यपि॥ 1.100

The two varieties of alaṅkāras, śabda and artha, are discussed under the eponymous heads of citra. Following Bhaṭṭa-gopāla, Sāyaṇācārya enlists six types of śabdālaṅkāra: vakrokti, anuprāsa, yamaka, śleṣa, citra and punaruktavad-ābhāsa. Although the author was familiar with Kuntaka’s conceptualization of vakrokti as an all-encompassing poetic concept, he has restricted it only to śabdālaṅkāra.

In the case of arthālaṅkāras, the text as it stands now discusses only three: upamā (fully along with its varieties), ananvaya and upameyopamā (cursorily). In explaining the divisions of upamā such as śrautī and ārthī, the author has followed the model of Mammaṭa and not those of Ruyyaka, Hemacandra and Bhoja. Ruyyaka exercised a potent influence on later aestheticians in the classification of alaṅkāras; nonetheless, Sāyaṇācārya does not follow him. The reason for this is perhaps the influence of Ekāvalī, a text of the ‘praśasti’ type after which Alaṅkāra-sudhānidhi is modelled.

[1] Ref: Abhinavagupta’s unequivocal proclamation: न चैते प्रीतिव्युत्पत्ती भिन्नरूपे एव, द्वयोरप्येकविषयत्वात्। (Locana, 3.14)

[2] Evidently, Sāyaṇācārya had Bhaṭṭa-tauta’s famous verses in mind in framing this definition: “…तदनुप्राणनाजीवद्वर्णनानिपुणः कविः। तस्य कर्म स्मृतं काव्यम्॥” (Quoted in Kāvyānuśāsana, 1.3). Likewise, he is indebted to Daṇḍī for the pregnant phrase ‘rasa-bhāva-nirantara’ (Kāvyādarśa, 1.18)

[3] इह हि तावद्भामहोद्भटप्रभृतयश्चिरन्तनालङ्कारकाराः प्रतीयमानमर्थं वाच्योपस्कारकतयालङ्कारपक्षनिक्षिप्तं मन्यन्ते। तथा हि—पर्यायोक्त-अप्रस्तुतप्रशंसा-समासोक्ति-आक्षेप-व्याजस्तुति-उपमेयोपमा-अनन्वयादौ वस्तुमात्रं गम्यमानं वाच्योपस्कारकत्वेन “स्वसिद्धये पराक्षेपः परार्थं स्वसमर्पणम्” इति यथायोगं द्विविधया भङ्ग्या प्रतिपादितं तैः। रुद्रटेन तु भावालङ्कारो द्विधैवोक्तः। रूपक-दीपक-अपह्नुति-तुल्ययोगितादावुपमाद्यलङ्कारो वाच्योपस्कारकत्वेनोक्तः। उत्प्रेक्षा तु स्वयमेव प्रतीयमाना कथिता। रसवत्प्रेयःप्रभृतौ रसभावादिर्वाच्यशोभाहेतुत्वेनोक्तः। तदित्थं त्रिविधमपि प्रतीयमानमलङ्कारतया ख्यापितमेव। वामनेन तु सादृश्यनिबन्धनाया लक्षणया वक्रोक्त्यलङ्कारत्वं ब्रुवता कश्चिद्ध्वनिभेदोऽलङ्कारतयैवोक्तः। केवलं गुणविशिष्टपदरचनात्मिका रीतिः काव्यात्मत्वेनोक्ता। उद्भटादिभिस्तु गुणालङ्काराणां प्रायशः साम्यमेव सूचितम्। विषयमात्रेण भेदप्रतिपादनात्। सङ्घटनाधर्मत्वेन शब्दार्थधर्मत्वेन चेष्टेः। तदेवमलङ्कारा एव काव्ये प्रधानमिति प्राच्यानां मतम्। वक्रोक्तिजीवितकारः पुनर्वैदग्ध्यभङ्गीभणितिस्वभावां बहुविधां वक्रोक्तिमेव प्राधान्यात्काव्यस्य जीवितमुक्तवान्। व्यापारस्य प्राधान्यं च काव्यस्य प्रतिपेदे। अभिधानप्रकारविशेषा एवालङ्काराः। सत्यपि त्रिविधे प्रतीयमाने व्यापाररूपा भणितिरेव कविसंरम्भगोचरा। उपचारवक्रतादिभिः समस्तो ध्वनिप्रपञ्चः स्वीकृतः। केवलमुक्तिवैचित्र्यजीवितं काव्यं न व्यङ्ग्यार्थजीवितमिति तदीयं दर्शनं व्यवस्थितम्। भट्टनायकेन तु व्यङ्ग्यव्यापारस्य प्रौढोक्त्याभ्युपगतस्य काव्यांशत्वं ब्रुवता न्यग्भावितशब्दार्थस्वरूपस्य व्यापारस्यैव प्राधान्यमुक्तम्। तत्राप्यभिधाभावकत्वलक्षणव्यापारद्वयोत्तीर्णो रसचर्वणात्मा भोगापरपर्यायो व्यापारः प्राधान्येन विश्रान्तिस्थानतयाङ्गीकृतः। ध्वनिकारः पुनरभिधातात्पर्यलक्षणाख्यव्यापारत्रयोत्तीर्णस्य ध्वननद्योतनादिशब्दाभिधेयस्य व्यञ्जनाव्यापारस्यावश्याभ्युपगम्यत्वाद्व्यापारस्य च वाक्यार्थत्वाभावाद्वाक्यार्थस्यैव च व्यङ्ग्यरूपस्य गुणालङ्कारोपस्कर्तव्यत्वेन प्राधान्याद्विश्रान्तिधामत्वादात्मत्वं सिद्धान्तितवान्। (Alaṅkāra-sarvasva, 1.1 vṛtti)

[4] तददोषौ शब्दार्थौ सगुणावनलङ्कृती पुनः क्वापि॥(Kāvya-prakāśa, 1.4)

References

- A Descriptive Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, Madras (Vol. 22; Ed. Kuppuswami Sastri, S). Madras: Superintendent, Government Press, 1918

- Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department. Mysore, 1908

- Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department. Mysore, 1914–15

- Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department. Mysore: University of Mysore, 1933

- Beginnings of Vijayanagara History. Heras, Henry. Bombay: Indian Historical Research Institute, 1929

- Contribution of Andhra to Sanskrit Literature. Sriramamurti, P. Waltair: Andhra University, 1972

- Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts (Vol. VIII; Ed. Malledevaru, H P). Mysore: Oriental Research Institute, 1982

- Early Vijayanagara: Studies in its History and Culture (Proceedings of S. Srikantaya Centenary Seminar; Ed. Dikshit, G S). Bangalore: BMS Memorial Foundation, 1988

- Epigraphia Carnatica (Vol. 6; Ed. Rice, Lewis B). Mysore Archaeological Series, 1901

- Epigraphia Indica (Vol. 3; Ed. Hultzsch, E). Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1979 (Reprint)

- History of Sanskrit Poetics (2 volumes). De, Sushil Kumar. Calcutta: Firma K L Mukhopadhyay, 1960

- History of Sanskrit Poetics. Kane, P V. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1971

- Jayadāman. Ed. Velankar, H D. Bombay: Haritosha Samiti, 1949

- Karnāṭakadalli Smārta-brāhmaṇaru: Nele-Hinnele (Kannada; Ed. Anantharamu, T R). Bengaluru: Harivu Books, 2023

- Kṛṣṇa-yajurveda-taittirīya-saṃhitā (with Sāyaṇa-bhāṣya). Pune: Ananda Ashram, 1900

- Mādhavīyā Dhātuvṛtti (Ed. Shastri, Dwarikadas). Varanasi: Prachya Bharati Prakashana, 1964

- Mysore Gazetteer (Vol. 2, Part 3; Ed. Rao, Hayavadana C). Delhi: B R Publishing Corporation, 1927–30

- New Catalogus Catalogorum (Vol. 1; Ed. Raghavan, V). University of Madras, 1968

- Pañcadaśī-pravacana (Kannada). Sharma, Ranganatha N. K R Nagar: Vedanta Bharati, 2003

- Parāśarasmṛtiḥ (with Mādhavācārya’s commentary; Ed. Candrakānta Tarkālaṅkāra). Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, 1974

- Puruṣārtha-sudhānidhi (Ed. Chandrasekharan, T). Madras: Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, 1955

- Sayana. Modak, B R. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1995

- South Indian Inscriptions (Vol. 4; Ed. Sastri, Krishna H). Madras: The Superintendent, Government Press, 1923

- Subhāṣita-sudhānidhi (Ed. Krishnamoorthy, K). Dharwar: Karnatak University, 1968

- Taittirīya-brāhmaṇa (Vol. 3; Ed. Godbole, Shastri Narayana). Pune: Ananda Ashram, 1979

- Uttankita Sanskrit Vidya-Aranya Epigraphs (Vol. 1, Vidyaranya). Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1985

- Vibhūti-puruṣa Vidyāraṇya (Kannada). Ganesh, R. Hubli: Sahitya Prakashana, 2011

- Vidyāraṇyara Samakālīnaru (Kannada). Gundappa, D V. Hubli: Sahitya Prakashana, 2023

To be continued.