Financial Difficulties and Higher Studies

Dr. P V Kane ('PVK') spent most of his time studying and writing with such single-minded devotion that we wondered what sort of financial position he was in. PVK himself has written that there was hardly any money he made from writing close to seven thousand pages; on the contrary, it cost him a great deal of money – in addition to the years he spent working on it. Dr. Shantaram Kane ('SK') told us that PVK’s active legal practice and providing legal opinions were the source of his income. He was a senior advocate in the Bombay High Court and was one of the most sought-after lawyers in the whole of Bombay Presidency on disputes pertaining to property, succession, and so forth. Indeed, he was considered an authority on Hindu Law and his opinions were sought by many, including High Court Judges in certain cases. Before starting his practice in law, he worked as a professor – and there’s a separate story behind how he started teaching. PVK didn’t inherit much ancestral wealth and most of the possessions were self-acquired.

PVK came from a middle-class family with limited means. He had to forgo his chance of studying at Harvard University despite being offered a scholarship. After his master’s degree, he was offered a scholarship from Harvard University’s Department of Oriental Studies. PVK was also keen to join but needed a princely sum of three thousand rupees to travel to the United States. His father, a small-town lawyer at a Taluka place, told him that he did not have the money to send him to Harvard. Despite the tuition fees being waived due to receiving a scholarship, money had to be paid for clothes, the long journey to the US, and for the initial settling down before the start of scholarship funds. The thwarting of his keen interest due to the financial situation of his father had irked PVK and impacted his mind so much that years later he would offer to sponsor his grandson when SK got a similar offer from a reputed university in the US. “My grandfather didn’t give me much career advice. He told me to study whatever I liked and what I excelled at. Irrespective of what I wanted to study and where I wanted to study, he told me that I should not think about the money. Pursuing higher education in the best possible institution is important!” said SK.

After PVK completed his law degree, he set out to enrol himself as an advocate under the Bar Council, which was then controlled by the British. The fees to get enrolled in the bar wasn’t nominal and one needed to get a certificate from a senior lawyer before he could be admitted to the Bar. PVK went to a senior advocate, who told him, “In spite of the fact that you’re a brilliant young man, I want you to come back when you confirm that you have savings of at least three thousand rupees.” He went on to explain the logic – “You need that amount to take care of the Bar Council fees, clothes, and enough to sustain your family for two years without any income from practice.” He promised to give him the certificate once PVK had that money.

Upon his senior’s counsel PVK toiled hard, took private tuitions for students in law subjects as well as Sanskrit, wrote supplemental readings for high school – Gadyāvalī [Prose] and Padyāvalī [Poetry] – and in less than three years earned the required money.

The university in which PVK studied made a fortunate blunder of not appointing him to the post of a lecturer despite his impeccable academic credentials. As per their records, presumably at some time when PVK was a teacher of Sanskrit, a mention was made in his file that he was “pro-nationalist.” This was a sufficient black mark to be considered unsuitable in a government college. Also, in those days, Citpāvana-brāhmaṇas in Maharashtra were considered as troublemakers by the British authorities.

This forced PVK to enrol at the Bar and commence his practice.

Self-imposed Diet and Palliative Remedies to Overcome Health Issues

If finance strained PVK during his early days, his health would strain him from his sixteenth year until the end. It was during his final year in school that he had suffered from severe stomach pain and lost a year. Many years later, this was diagnosed as a severe duodenal ulcer, also called ‘gastric ulcer.’ As a young student, he found out by trial and error that he had to have a simple diet with absolutely no spices or anything sour. Even a fully ripe Alfonso mango was not acceptable. Plain boiled rice, wheat, milk, and plain boiled vegetables were tolerated. Despite this, if the pain became unbearable, he would take milk of magnesia (Magnesium Hydroxide) and milk. No amount of medication or visits to the doctor helped him recuperate.

Often, in the midst of an argument in court, he would get such gastritis attacks that forced him to stop the arguments. He would immediately request the Judge for a few minutes’ break, go out of the court hall, gulp down a syrup of antacid with some milk, wait for a few seconds, and return to continue his arguments.

Much later, when PVK’s son was studying at Cambridge, PVK—then fifty-seven years old—visited Europe and made a special trip to Vienna to meet a world-famous gastroenterologist. The doctor examined PVK and asked him how he was living with this terrible problem. PVK explained the issue, the effects on his body, the rigorous diet, and the palliative medicines he was using as and when required. After listening to PVK for a while, the doctor said, “Dr. Kane, I think you know about your ulcer better than any doctor. I don’t think I can suggest anything except saying – please continue with whatever you are doing. Your medicine appears to be working well for you!”

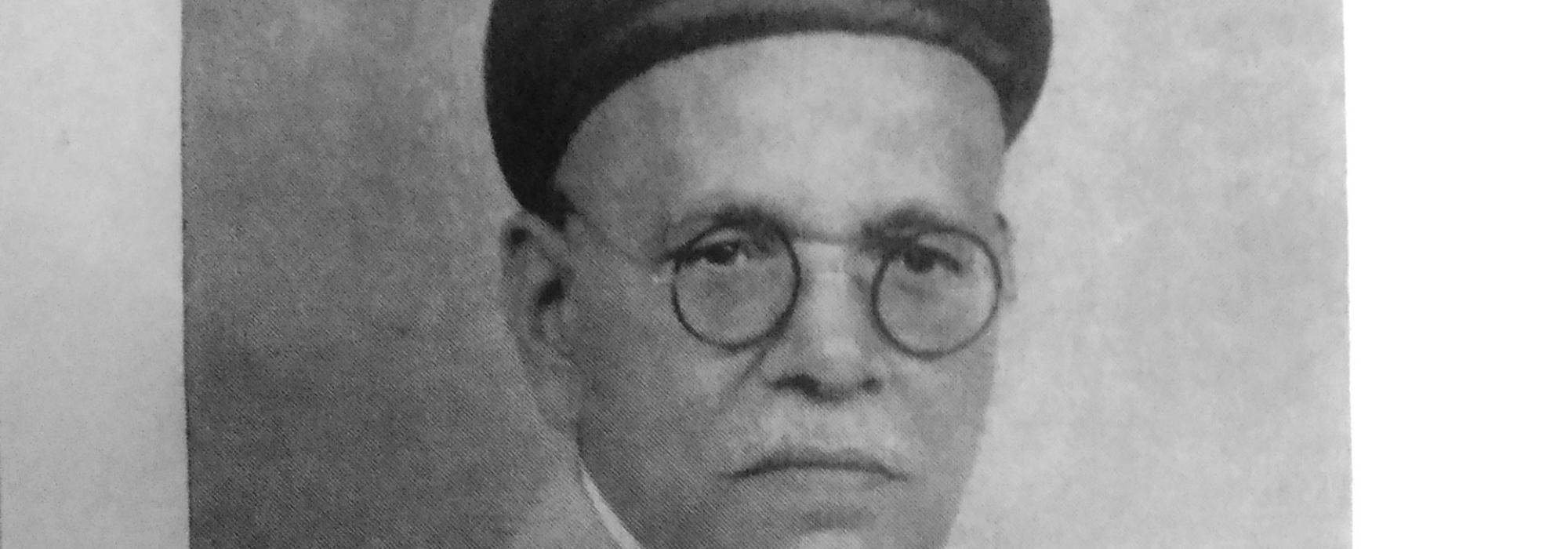

P V Kane’s Portrait

[[{"fid":"9777","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"left","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Portrait of Dr. P V Kane","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Portrait of Dr. P V Kane"},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default","alignment":"left","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Portrait of Dr. P V Kane","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Portrait of Dr. P V Kane"}},"attributes":{"alt":"Portrait of Dr. P V Kane","title":"Portrait of Dr. P V Kane","style":"height: 448px; width: 310px; float: left;","class":"media-element file-default media-wysiwyg-align-left","data-delta":"1"}}]]Waves and waves of such anecdotes, narrated in an impressive manner by SK, had made us travel back in time. I looked at the huge clock hung in the living room and realised that we had spent well over two hours at SK’s house. A series of missed calls on the mobile (from our other friends who were waiting at the hotel) also signalled that it was time to head back. The three of us expressed our gratitude to SK and bid him goodbye. Just before we rose from our chairs, we all once again looked at the painted portrait of PVK. Below that portrait there were other family photos, in smaller sized frames. I pointed to the portrait and asked, “That’s a painting of Dr. Kane right? Have you kept any other photos of his here, in the living room?”

SK looked at them and said, “No, that’s the only one. But yes, that is a painting. It so happened that when my grandfather was made the Vice-Chancellor, his eldest son-in-law insisted that his portrait be painted. A well-known painter of those days was requested to paint it. This is actually a photo of that portrait. The original painting is in the Royal Asiatic Society.”

We all offered our salutations to that portraitand took his leave.

Conclusion

Men may come and men may go but legends go on forever. They remain to live and influence the world in their own way. Some live through their actions and take a prominent part in the annals of history. The fame of certain men may outlive their life by a few generations. Only a handful of people exist who contribute so much to a certain field that forgetting them would mean losing an entire subject. As long as Indology lives, as long as the Dharma-śāstras are spoken about, as long as Indian culture is researched upon, and as long as one relates our ancient texts with today’s laws and practices, Dr. Pandurang Vaman Kane’s name and work shall remain. His work was no less than a great tapas and he is no less than a ṛṣi. For a Westerner who wishes to know India and more importantly, for an Indian who wishes to know the significance of his roots and who aspires to learn more, Dr. Kane will prove to be a peerless guide, for he lived and breathed sanātana-dharma.

sarvam śivam

Concluded.

My heartfelt thanks to Dr. Shantaram G Kane, the grandson of Dr. P V Kane, for sharing so many wonderful anecdotes about his grandfather with me and my friends. Further, he promptly reviewed the present essay, offering wonderful suggestions as well as fact-corrections. I wish to express my thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh and Dr. S L Bhyrappa for encouraging me to record the highlights of my meeting with Dr. Shantaram Kane. Thanks to Hari Ravikumar for his thorough editing of the essay.