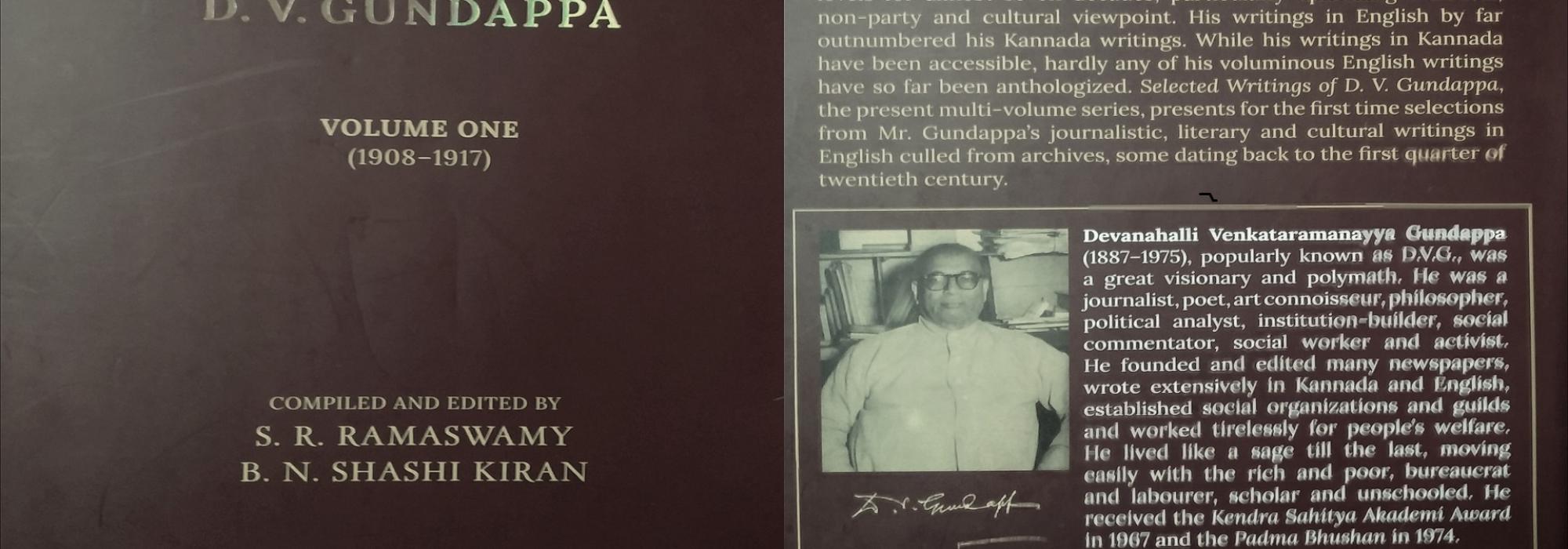

DVG never sought recognition. When the Jnanapith Award was first instituted, Maṅkutimmana Kagga, one of his major works, came before it for consideration. When one of his friends was indignant about this work not winning the award, DVG replied in his characteristic self-effacing, humorous manner: “Why do I want a lakh of rupees? Do I not look well-fed?” He went on to make a profound observation: “The idea of competitive prizes for literature is basically absurd. My whole nature rises in revolt against it. Valmiki and Vyasa and Potana and Thyagaraja are our ideals. Did they compete for anybody’s favours?” (Kaggakkoṃdu Kaipiḍi, p. 527). In 1970, his admirers organized a felicitation programme in recognition of his services to public affairs spread over six decades. The public of Bengaluru honoured him and presented a purse of one lakh rupees. DVG donated the entire amount to Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs. In fact, he had agreed to attend the event only on the condition that he would be allowed to donate the money to the Institute. He received several awards and honours such as Honorary D. Litt. from the University of Mysore (1961), Kendra Sahitya Akademi Award (1967) and Padmabhushan (1974).

The source of DVG’s conviction was his attitude to life. He looked at the world as an abode of the Supreme (brahmapattana) and at himself as a mendicant wandering on its streets (brahmapattana-bhikṣuka). He firmly believed that our duty here is to make life pure, beautiful and elevating. The celebration of life, he thought, is not a mark of materialism but the essence of the Vedas.

His ideal in life was a vanasuma, forest flower. When a flower blooms somewhere deep in a forest, there is nobody to appreciate it. Colour, shape, tenderness and all its other fine qualities go unsung. Nobody writes a poem on it; nobody offers it to a deity. Even so, it breathes a fresh fragrance into the air and quietly withers away. DVG thought we should live in this manner: organic evolution leading to self-discovery should be our sole objective. DVG unconditionally practised what he preached. And therein lies the greatness of his ideal.

* * *

DVG wrote more than twenty thousand pages in English and Kannada. While his English writings largely deal with politics and rarely foray into culture, literature and philosophy, his works in Kannada cover a wide range of literary genres. Among his Kannada writings are children’s literature, reminiscences, pen portraits, biographies, discursive essays, literary criticism, plays, lyrical poems, songs, philosophical poetry, analytical poetry, socio-political writings, spiritual works, contemporary commentaries on traditional treatises, translations and adaptations.

An in-depth understanding of seminal concepts such as truth, goodness, beauty and dharma underpins all his writings. He saw no difference between truth and goodness, truth and beauty, politics and philosophy. I would like to quote his own words.

On truth and goodness:

The good can never be viewed as apart from the true … It is significant that Sanskrit has the same word for the truly good as well as for the truly existent. That word is Sat. Sat is both eternal being and indestructible good. The supremely true is the supremely good … The nature of the right must be derived from that of the good and the nature of the good from that of the true. (Selected Writings of D. V. Gundappa, vol. 5, pp. 9–10)

On philosophy and politics:

Philosophy and politics are … two aspects of the same activity – pursuit of the good … The statesman concretizes and fulfils what the philosopher initiates and commends. Between them, they complete the service of the social good. Philosophy without the instrumentality of statesmanship is ineffectual longing and vain fancy-play. Politics without the inspiration of philosophy is a welter of blind forces and a raffle for the adventurous. (Selected Writings of D. V. Gundappa, vol. 5, p. 11)

On ṛta, satya and dharma:

Ṛta is a self-existent instinct of man … It acts in us on the instant, as a sudden flash, lighting up the shape of the true in any situation. It is our inner witness and usually our first witness. Satya is ṛta confirmed … or action-worthy truth. And satya in action is dharma … Dharma […] based upon a rational appreciation of the relative values of things of the body and of the soul, is justice or due satisfaction of the claims of each entity in a conflict. It is generosity or willingness to share the good things one has with those who have them not … It is harmony in relationships and grace in behaviour. It is not the suppression but the regulation of desire. It is the introduction of a rational order into the chaotic promptings of the body and the mind. It is in life what balance and proportion are in a picture. (Selected Writings of D. V. Gundappa, vol. 6, pp. 49–51)

An ancient epithet eminently suits DVG – dharmaprāṇa. His exposition of dharma is a valuable contribution to Indian philosophical thought. This rootedness in dharma helped him interpret ancient treatises as applicable to our time, without ever injuring their intent. His works on Puruṣasūkta, Īśāvāsyopaniṣad and most importantly Bhagavadgītā testify this fact.

DVG called his book on the Gītā as Jīvanadharmayoga and looked it as a work that can enhance the quality of our worldly life. He envisioned it primarily as a jīvanaśāstra and then as a mokṣaśāstra. He coined meaningful alternatives to the names of the Gītā’s chapters, which succinctly capture their content. I will give two examples: DVG termed Arjunaviṣādayoga as Prākṛtakāruṇyayoga and Sāṅkhyayoga as Tattvavivekayoga. While the former perfectly describes Arjuna’s misplaced and inconsiderate compassion—which is the crux of the first chapter—the latter immediately clears a common misconception that the second chapter deals with the Sāṅkhya school of philosophy. The introductory essay not only contextualizes the work but also serves as a most reliable guide to students of Indian philosophy. DVG explains concepts such as anubandha-catuṣṭaya, sādhana-catuṣṭaya, the puruṣārthas and adhikāribheda with great clarity, defines the technical terms of philosophy in a comprehensive manner, shows the subtle shades of karma and dharma and expounds on the contemporary relevance of this ancient text. At the level of form, Jīvanadharmayoga is a veritable model for non-fiction writing. It illustrates the fact that technical subjects can be explained with warmth and literary flair without sacrificing rigour and clarity.

DVG explained the equivalence of truth and beauty in poetic works such as Nivedana, Śrīcènnakeśava Antaḥpuragītagaḻu and Śṛṅgāramaṅgalam. Inspired by John Keats’ famous poem Ode on a Grecian Urn, DVG amplified its essence in Indian terms using the illustration of the madanikā images in the Belur temple. Antaḥpuragīta is a unique work that demonstrates the happy fusion of fundamental arts such as literature, music and sculpture. A similar work perhaps does not exist in any other Indian language.

Vālmīki, Vyāsa and Kālidāsa are the best representatives of India’s literary heritage. DVG has made these poets more meaningful to us through many of his writings. In the forewords he wrote to Vidvān N Ranganatha Sharma’s Kannada translation of the Rāmāyaṇa, he has explained the kind of mindset that is essential to the study of epic literature. He asserts that we should approach an epic as a child would her mother, with natural and effortless trust. He urges us to guard against over-interpretation caused by stretching the words of the poem to extreme limits. Further, he explains that poetry presents only a ‘verisimilitude of truth’ and not truth itself and upholds ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ as a requisite in poetic appreciation.