In the previous part of this essay, I traced the origin of the Mackenzie Manuscripts to Col. Colin Mackenzie discovering his life’s mission after his interactions with the Madurai Brahmins whose learning was prolific, vast, deep and multifaceted, and concluded with a mention briefly of their contents.

Quantity is also a Quality

The chief value of the Mackenzie Manuscripts is the sheer lavishness of their abundance, making true the dictum that sometimes, quantity is also quality. When we consider that we have an overwhelming total of 1,568 literary manuscripts, 2,070 Local tracts, 8,076 inscriptions, and 2,159 translations, 79 plans, 2,630 drawings, 6,218 coins, and 146 images of primary historical sources, we can only begin to fathom the extent of and the scope for study that this treasure affords us.

After Colin Mackenzie’s death in 1821 and the subsequent acquisition of the manuscripts from his wife Petronella, Horace Hayman Wilson, Secretary to the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal was the first to volunteer to catalog them in 1838. His work in two volumes was so meticulous and thorough that almost immediately upon its publication, copies ran out and the consequent enormous demand created a situation where used copies fetched handsome prices at book auctions. Eventually, a one-volume copy was published at affordable prices. [i]

Wilson’s efforts were later supplemented by F.W. Thomas, Bladgen, H.N. Randle and others. Given the sheer volume of the Manuscripts and the daunting effort required to lend them order, structure, and coherence, Wilson’s work quite obviously contained imperfections. And so, after years of patient study, Rev William Taylor tried to correct them in his Catalogue Raisonne of Oriental Manuscripts in three volumes, in the Government Library, Madras in 1862. Working alongside him was Brown, who tackled the Telugu Manuscripts and restored a significant number of Local Records totaling up to sixty-four volumes. Five other volumes were also restored but the originals, regrettably, were lost. A part of the collection is now in the India Office Library, London. [ii]

Other notable Indian scholars and historians who’ve studied these Manuscripts include the South Indian history scholars, K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, S.K. Aiyangar, T.V. Mahalingam, and others. The Madras University Mackenzie Manuscripts summaries, under T.V. Mahalingam’s editorship, mainly relate to South India’s history. They number 224 in total including Telugu, Kannada, Tamil and Malayalam, with Telugu being the highest (40%), Kannada (25%) and the remaining in Tamil and Malayalam.

Assessing the Value

To begin to assess the value of the Mackenzie Collections, we can cite the almost unanimous opinion of all these scholars and catalogers who aver that the “most important part of the collection relating to inscriptions” is the three-volume “South Indian Temple Inscriptions” published by the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library, Madras. These contain the “texts of the eyecopies of inscriptions” made by Mackenzie’s team that visited various parts of Tamil Nadu, Malabar, Cochin, Andhra Pradesh and Mysore regions. [iii]

First, among the literary collections, we have the Kaifiyats (Local Tracts), local history, biographies, Puranic legends, accounts of men, and places. More importantly, and perhaps a little known fact today is that these manuscripts offer us rich primary sources in the form of Jain literature comprising plays, stories, poems, and technical subjects like philosophy, the monastic order, astronomy and astrology.

For the purposes of this essay, we can categorize the information contained in the Mackenzie Manuscripts as describing the following aspects of South Indian history:

- Political conditions

- Administrative systems

- Social structures

- Religious life and conditions

A common, twofold difficulty that all researchers and scholars of these manuscripts describe relates to the long period they encompass and evince some skepticism regarding their historical value. However, they equally agree that despite this shortcoming, these manuscripts have their “own place in…historical research in India…and maybe used as circumstantial evidence…to…supplement the results arrived at from other sources and furnish further details on the subject.” [iv] As T.V. Mahalingam and T.N. Subramanian—one of the critical editors of these texts—say, a comparative analysis of the inscriptional eyecopies and independent researches unearthed by the Epigraphy Department bears testimony to this fact, and that but for Colin Mackenzie, these inscriptions, land records, and Local Tracts would’ve been lost forever, making the reconstruction of history almost impossible. [v]

Political History of South India

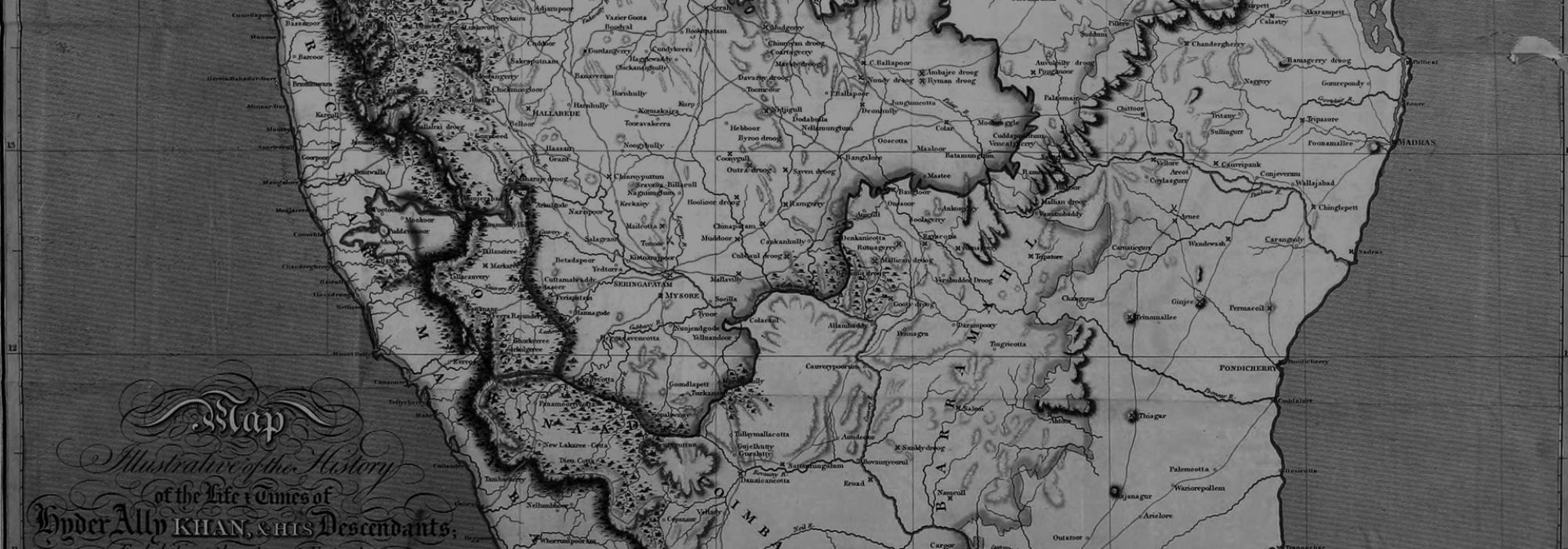

The Manuscripts cover both a lengthy and wide period and relate to the history of South India from very early times. They deal with the histories of the Chera, Chola and Pandya dynasties from the primigenial period in a stray fashion, to put it loosely. Post the end of the Pandya dynasty, they give perhaps the most definitive, first-hand accounts of the entire period starting with the Vijayanagara period, of Mysore under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, all the way up to slightly before Colin Mackenzie’s own time.

Perhaps part of the reason for the aforementioned skepticism on the part of the Manuscripts scholars is due to the abundance of local legends tracing the origins of these royal dynasties to Mahabharata heroes like Janamejaya and as such, were not considered as dependable and authentic historical accounts to be relied upon for accurate chronology. [vi]

However, as we saw in the first part of this essay, “from the 16th century onwards, the manuscripts are of greater value” to decipher and reconstruct the history of south India. The reason is the Vijayanagara Empire, which in the words of Prof. Mahalingam goes thus:

The glory that was Vijayanagar, the disastrous battle of Talikota…which ended that memorable epoch in Hindu India…and the confusion that followed in the wake of its eclipse were still fresh in popular mind. It is but natural that the manuscripts should dwell at length on this purple patch of Indian history…as the languages patronized most by the Vijayanagar dynasty were Telugu and Kannada, the majority of the manuscripts are in these two languages…as the manuscripts…indicate, there were successive migrations of people from the north to the south, a recurring phenomenon in Indian history, following the conquest of the Tamil areas…a very large number of manuscripts relate to such migrations and the incidental origin of various principalities called Palaiyams with their heads, the Palaiyakkarar (Poligar). [vii] [Emphasis added]

Indeed, the Professor’s note on migrations is more significant than we realize. From the earliest waves of Muslim invasions and for much of the inveterate Muslim rule, the history of India is the history of chequered migrations of Hindus from and to various parts of its geography. As such, this topic by itself merits a detailed, scholarly and rigorous study, which will also offer valuable insights into the reinterpretation and reconstruction of Indian history.

Administrative History

On the point of historical reinterpretation and reconstruction, a pervasive narrative both in the scholarly and popular realms holds that but for the British, India wouldn’t have had a robust administrative machinery. Some even go to the extent of claiming that viceroys like Curzon introduced these systems for the first time ever in India’s long history.

However, the Mackenzie Manuscripts—among other historical records—show exactly the opposite. As a representative sample, we can simply look at the awe-inspiring Palaiyam system. Indeed, these Manuscripts can be regarded as the most definitive primary sources for tracing the origin of the Palaiyam system, something that endures in many ways, even today.

The Palaiyam system arose on account of several factors: as a reward for services rendered to the Southern Pandya rulers, in some cases when the Reddi zamindars of Nellore rendered similar services to the Raja of Madurai, and for offering military assistance to the Vijayanagar kings against their Muslim enemies.

A Palaiyam or Paliyapattu can be thought of variously as a tiny principality comprising numerous villages and/or towns headed usually by a commander or a military leader assigned the title of a Poligar or Palaiyakkarar or in Kannada, aPalegara. One of the most powerful Palegara dynasties was the Palegaras of Chitradurga.

Eventually, all of the Palaiyams came under British control who ruthlessly disposed of the Poligars after their utility had ceased.

As Prof. Mahalingam observes, these Manuscripts are “useful for a study of administrative institutions in the region” for the 16th to 19th century period, and needs to be quoted at length:

The Tamil Kaifiyat[s]…throws welcome light on the institution of the Palaiyam system in the Tamil country. It makes a clear distinction between ownership villages and Kavali villages…[and] gives the difference between Jagir and Poligarship. Others…give an account of the origin of a number of Palaiyams in…the 16th and 17th centuries and enable us to form an idea of the general character of the Palaiyam system [which was] …feudal and military in character [in which]…the Poligar [had to maintain a standing army and pay annual tribute to the King]…the Kaval system…was a…police organization where a few persons in a locality were…responsible for the maintenance of peace…and protection of the people…for which they were assigned Kaval lands…the [other] institution of Kumaravargam…[accorded the status of Princes to a few ministers]…This reminds us of a [similar practice]…in earlier periods…under the rulers of the Chalukya, Hoysala and Vijayanagar dynasties. [viii]

A similar administrative system existed in the Telugu country in the form of Dandakaviles or just Kaviles, which were village registers recording information about the “political, religious, social and economic conditions of the village. They were in…the custody of the village Karnam [broadly, accountant] who would record…them…and pass them on to his successor.” [ix]

Mackenzie Manuscript No. 160, Section 10 mentions the encyclopedic Athavana Vyavaharatantra, which Prof. Mahalingam claims is “indispensable for a study of the administrative institutions of South India from about the 17th century.” [x]

In a line, the foregoing discussion on the Palaiyam, Kaval and other administrative systems simply shows the astonishing, sturdy, flexible, enduring, and resilient systems that India’s age-old political and administrative acumen dating back to Kautilya, had birthed and whose memory was preserved for centuries in both theory and application. At once, it’s also a splendid tale of the unity and integrity of both administrative systems and their linguistics no matter the region of India.

Administrative and Linguistic Unity and Integrity

It’s also no coincidence that today’s Reddys are largely renowned as landowners given their centuries’ long role as rulers, warriors, chieftains, and administrators.

Equally, this unity and integrity shows most clearly when we consider a small instance of etymology. The Tamil term “Palaiyam” becomes “Palayam” in Telugu and “Palaya” (or Palya) in Kannada. This etymology can be traced back to the Sanskrit roots of the word, “Paala” (a masculine vocative singular stem) used in the sense of a “guard, keeper, protector” and so on.

Indeed, when we notice the names of localities and areas of places in south India today, it reveals an astonishing tale of cultural, linguistic and historical unity. For example, in Bangalore we still have localities named “Bovipalya,” “Sultanpalya,” “Srigandha Kavalu,” and so on. The same etymological fact applies to regions elsewhere in South India.

Prof. Mahalingam also refers to this unity when he notes that “[A]n interesting feature of the manuscripts is that they are in the different languages of South India, but do not in all cases conform to the language of the region whose history they record.” [xi]

The Mackenzie Manuscripts also clearly show how the aforementioned migrations “contributed to the admixture” of north and south Indians and “explains the presence” even today of a “large number of Telugu and Maratha speaking population in rural Tamil Nadu. And more importantly, how there was “no friction between the indigenous Tamil…people and the camp followers of the new rulers speaking Telugu or some other language.” [xii]

This absence of linguistic animosity—compare today, the unfortunate, linguistic rancor that has plagued much of post Independence politics, dragging down development, inflaming linguistic and other divisive passions, etc with Tamil Nadu as the greatest and most tragic example—merits a separate, in-depth study if only to understand the calamity of independent India’s hasty decision to create language-based states.

Rich Primary Source of Social Life

Almost intertwined with the wealth of firsthand descriptions of administrative systems are the vivid details of the social life of the period especially between the 16th and 18th Centuries.

Indeed, for an understanding of the social life of the period, these Manuscripts are the invaluable and authentic primary sources—more pointedly, they offer scenic details of the routine life of a host of village communities in all of south India. These details underscore, yet again, the underlying cultural unity of India, varying only in local customs and traditions.

Very significantly, Prof. Mahalingam observes how, although the so-called caste system was rigid, “there [is] no evidence of caste or communal hatred and jealousy.” He also notes that the “outstanding feature that emerges from…these manuscripts is that while the caste system (sic) continued to be rigid, the repeated movements of people from the north which followed in the wake of [Muslim] conquests and the reverse process-exodus of the followers of the vanquished rulers created forces where were disrupting the caste system.” [xiii] [Emphasis added]

As an example, we can turn directly to Mackenzie Manuscript Number 53, which describes the Tamil work Jatinul Kaviyurai (literally, “Commentary on a metrical work named Jatinul,” authored by a certain Ulakanathan). This work can be taken up for independent study on its own.

Jatinul Kaviyurai offers an extraordinarily detailed listing of the so-called castes and occupations of each “caste” in Tamil Nadu. “He claims that the subject matter is based on the works of Veda Vyasa, Vaikhanasa Aagama, Suta Samhita andSuprabhedagama.” He also mentions the millennia-old scheme of division of society, social customs and traditions—for example, the Anuloma, Pratiloma and Vratyaoffspring—the different Saivas, and gives an account of seventy-nine castes. [xiv]

The Maravar Jati Kaifiyat in Manuscript Number 55 enumerates the seven subdivisions of the Marava tribe, their gotras, and social customs like Sati and widow remarriage. Their marriage rituals are also described in great detail. Some of these rituals and specifics of celebrations continue to this day among their descendants. The Maravars take on the honorific, “Thevar,” and are descended from a long lineage of warriors (Maravar = “Warrior” or “bravery”).

Similarly, the Malayalam Manuscripts give an exhaustive account of the complex and picturesque social order in Kerala including the customs and manners of the “wild tribe” of the Kunnuvar, as also that of mountain tribes, hunters, robbers, fishermen, weavers, and merchants.

Of interest is Manuscript Number 77 (Section 5) which gives a firsthand account of the “origin of the early settlements of Muslims and later of the moplahs on the Malabar coast.” [xv]

In passing, we see, even here, a linguistic and/or terminological unity when for example, the merchant tribe of “Komati” is described. There is also a “caste” known as “Komati” among the Telugu speaking people.

Temples, Places of Pilgrimage, and Saints

For eons, temples were the vibrant centers of cultural and religious life all over India, and continue to be so even today in smaller towns and villages, and preserve some superficial vestiges in cities.

Needless, the temple culture was inextricably braided with polity, economy and society. And as Prof Mahalingam notes, “the Mackenzie Manuscripts narrate the history of several important temples in South India…which still prove useful.”

In fact, the Mackenzie Manuscripts reveal the continuation of the time-honoured tradition of kings and rulers patronzing temples even those of sects different from theirs. The usefulness of these Manuscripts will be clear when we study the wealth of firsthand information they provide about important centres of pilgrimage like Ahobilam, Srisailam, Kanchipuram, Tiruvannamalai, Chidambaram, Palani, and Kanyakumari among others.

For instance, these Manuscripts vividly narrate the history of the Dikshitars of the Chidambaram temple, which continues to be valid and relevant for our own times when we recall the Supreme Court’s judgement on this important temple. Indeed, the very first Mackenzie Manuscript [xvi] titled “Account of the temple of Cidambaram in the Cola Country” begins thus:

The Hemasabhanatha Mahatmya in twelve chapters deals with Siva’s appearing as a mendicant in Darukavana, testing the mind of the sages, the arrival of Patanjali from Kailasa to Cidambaram…The God curbed the pride of…the sages…and danced a mystic dance in Cidambaram.

We can also glean the pervasive, pious and lasting influence of the Chidambaram temple that animated scores of saints, poets and commentators throughout the ages. Notably, in our own time, Ananda K Coomaraswamy’s immortal, classic essay The Dance of Shiva is a superb exposition of Chidambaram’s Lord Nataraja performing his cosmic Tillai, or dance.

The descriptive details of temples are also accompanied by the portrayal of the political and social life of the period. For example, the en masse depopulation of Hindus in and around Srisailam after Kurnool was occupied by Muslim nawabs.

Source of Jain History

The Mackenzie Collections are also important primary sources for the study of Jainism in South India including Jain centres of pilgrimage and learning in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

They contain valuable material about prominent Jain centres in Tamil Nadu including Koliyanur, Tirunarungondai, Tondur, Perumandur, Tirumalai (in Polurtaluk today), and Konakondla, Silpagiri, and Danavulapadu, and Chittamuru in Andhra.

Interestingly, Manuscript Number 12 gives a fascinating account of Padmanathapuram or ancient Mylapore—later, a part of Madras—where a Digambara Jain ascetic prophesies that the “city would be engulfed by the sea in three days.”

Manuscript 68 gives an exhaustive list of Jain literary works in Sanskrit, Prakrit and Tamil on such varied subjects as philosophy, poetry, prosody, grammar, ethics, mythology and “also on rules…for the monastic orders and lay followers.” [xvii]

Closing Notes

A couple of decades ago, the venerable Nani Palkhivala wrote thus:

It has been my long-standing conviction that India is like a donkey carrying a sack of gold — the donkey does not know what it is carrying but is content to go along with the load on its back. The load of gold is a fantastic treasure — in arts, literature, culture and some sciences like ayurvedic medicine — which we have inherited from the days of the splendour that was India. Adi Sankaracharya called it the accumulated treasure of spiritual truths discovered by the rishis.

And as we note, barring a few notable exceptions, not much has changed since Nani’s time. Indeed, they are notable simply because they’re not the norm. It’s also a profound sign of the times that, forget lay people, our cultural bodies, our universities, think tanks, and sprawling and well-endowed academies of higher learning have continued to take a serious disinterest in re-quarrying such immortal treasures as the Mackenzie Manuscripts.

This situation even when titans like Dharampal used these Manuscripts for their own researches; and just about sixty—seventy years ago, these Manuscripts were quoted extensively in say, the Asiatic Journal, the Madras Journal of Literature and Science, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, and so on.

At the very least, we’ll be doing a monumental national service if we study these Manuscripts and make them accessible to children in the form of comics, and in popular narratives like say historical fiction, a series in mainstream publications, television, digital outlets, and so on.

They lie in wait in England at the British Museum and the Oriental and India Office Collections of the British Library.

Postscript

When seeking guidance for this article from an elderly scholar, I asked him if it’s worth exploring the possibility of getting the Collections back to India. His reply: “No. It’s good that they are in England. To learn how to preserve them, we must first know their value.”

References

[i] Preface: The Mackenzie Collection. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Oriental Manuscripts: The Late H.H. Wilson, Esq, Calcutta 1882

[ii] Introduction: Mackenzie Manuscripts, Volume 1: University of Madras, 2011: Edited by Prof T V Mahalingam: p. xxiii

[iii] Ibid. p. xxiv

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid. p. xxv

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid. p. xxvii

[viii] Ibid. p. xxxi

[ix] Ibid. p. xxxii

[x] Mackenzie Manuscript No. 160, Section 10

[xi] Introduction: Mackenzie Manuscripts, Volume 1: University of Madras, 2011: Edited by Prof T V Mahalingam: p. xxiii

[xii] Ibid. p. xxvi

[xiii] Ibid. pp. xxxiii–xxxiv

[xiv] Mackenzie Manuscript No. 53

[xv] Introduction: Mackenzie Manuscripts, Volume 1: University of Madras, 2011: Edited by Prof T V Mahalingam: p. xxxv

[xvi] Mackenzie Manuscript No. 1: Section 1

[xvii] Introduction: Mackenzie Manuscripts, Volume 1: University of Madras, 2011: Edited by Prof T V Mahalingam: p. liv

Comments