Vālmīki also finds mention in the Śrīman-mahābhāratam too. In the sabhā-parva (7.19, *7.14 in critical text) Vālmīki’s presence in the court of Indra is mentioned by devarṣi Nārada. When bhagavān Śrī-kṛṣṇa goes to the court of Dhṛtarāṣṭra as the messenger, Vālmīki along with other maharṣis wish him success in the udyoga-parva (82.27, *81.27 in critical text). Later in droṇa-parva we see when Bhūriśravas has renounced the war and is in the state of dhyāna, Sātyaki beheads him. The kaurava army then ridicules him for committing the grave crime of attacking an unarmed warrior. Then Sātyaki answers thus -

अपि चायं पुरा गीतः श्लोको वाल्मीकिना भुवि |

न हन्तव्यास्-स्त्रिय इति यद्ब्रवीषि प्लवङ्गम ।

पीडाकरममित्राणां यत्स्यात्कर्तव्यमेव तत् ||-droṇa-parva 142.67-68, *droṇa-parva 118.48 in critical text, the relevant pada न हन्तव्यास्-स्त्रिय इति is missing.

The phrase “न हन्तव्यास्-स्त्रिय इति…” comes from Śrīmad-rāmāyaṇam yuddha-kāṇḍa 81.28/29 in southern recensions, (*critical text 68.27). When Indrajit is about to kill the ‘Māyā Sītā’, Hanumān cautions him saying, “Women are not to be killed..” for which he replies, “O Vānara! You might say that women are not to be killed. but we should always do whatever is required to make our enemies suffer!”

In the anuśāsana-parva 18.8-10 (*critical text 18.7-8), Vālmīki meets Yuddhiṣṭhira and narrates his story, “I argued with some of the munis once. They were angered and cursed me saying, ‘You’ll incur the brahmahatyādoṣa’ . Immediately the doṣa engulfed me. I took the refuge of Parameśvara, and propiated him through japa and finally was relieved from it due to his benevolence.”

The modern critics say “While the events of the Śrīmad-rāmāyaṇam happened earlier than the events of Śrīman-mahābhāratam, it was written later.” But we see that “अपि चायं पुरा गीतः श्लोको वाल्मीकिना भुवि…” is present in Śrīman-mahābhāratam, this suffices to prove that these arguments have no basis.

Śrīmad-rāmāyaṇam is a mahākāvya not a purāṇa. Poetry is always endowed with the capability of producing ānanda which is beyond this world. The beauty inherent in it is what makes it different from any other form of literature. As the great aesthetician Vāmana says, ‘kāvyam grāhyamalaṅkārāt saundaryamalaṅkāraḥ’ due to this very reason. The reasons for poetic beauty are manifold. The pada (words), the rīti (style), the śayyā (construction), the alaṅkāras (various figures of speech), guṇa (attributes), the bhāvas (feelings) and the rasas (emotions/sentiments) and so on. The metrical construct lends itself to melody enhancing the beauty of the work endowing it with a unique charm. But rasa is the primary source of life to all poetry. Aestheticians declare that indeed rasa is the very life of kāvya.

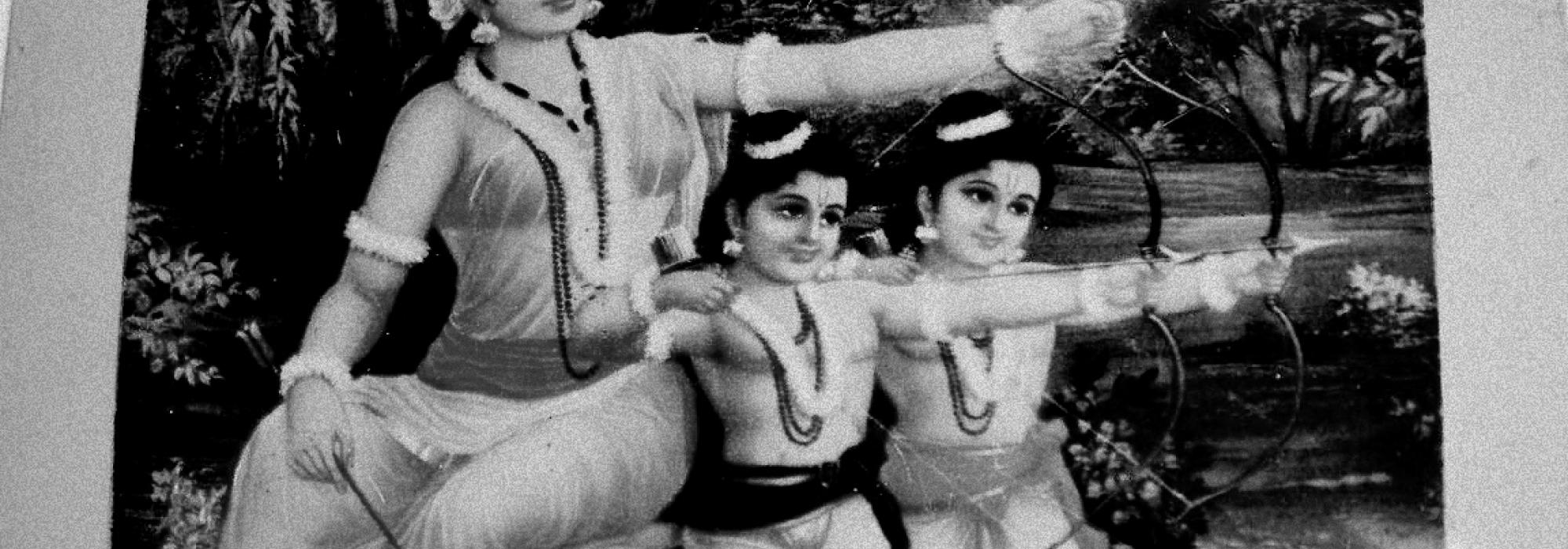

Rasa is of nine types - śṛṅgāra (love/passion), vīra (heroism), karuṇa (pathos), adbhuta (marvel), hāsya (humour), raudra (wrath), bībhatsa (disgust), bhayānaka (frightening), śānta (tranquility). We come to know that Śrīmad-rāmāyaṇam is filled with these rasas and was sung by Lava and Kuśa by the verse

रसैः शृङ्गारकरुणाहास्यरौद्रभयानकैः ।

वीरादिभिश्च संयुक्तं काव्यमेतदगायताम् ॥-Bālakāṇḍa 4.9

[The kāvya comprising of śṛṅgāra, karuṇa, hāsya, raudra, bhayānaka, vīra, and other rasas were sung by…(Lava and Kuśa)]

By ‘वीरादिभिश्च’ we should understand that adbhuta, raudra, śānta, too are present. For every rasa there is a fundamental state, these are called the sthāyibhāvas. The word ‘sthāyi’ means something which stays for a long time. When these fundamental states are suggested due to various reasons they become rasas. Rasa is never to be directly expressed by words. It is always implied or suggested. Such implication or suggestion of sthāyibhāvas manifest as rasas. The sthāyibhāvas are as follows - rati for śṛṅgāra, utsāha for vīra, śoka for karuṇa, vismaya for adbhuta, hāsa for hāsya, krodha for raudra, jugupsā for bībhatsa, bhaya for bhayānaka, śama for śānta. Then there are vibhāva, anubhāva, sañcāribhāva, and sāttvikabhāva, exposition on these terms are out of the scope of the current discussion.

There are ample examples of these rasas in Śrīmad-rāmāyaṇam. None of them seem artificially dragged into the plot just to showcase them. They naturally occur depending on the plot. Other than these Śrīmad-rāmāyaṇam is the treasure trove of other emotions like shame, envy etc. The mutual love and affection which exists between Śrī-rāmā and devī Sītā constitutes rati. It finds expression starting from the ayodhyā-kāṇḍa and continues till the very end. Once devī Sītā is kidnapped the separation which they both suffer constitutes vipralaṃbha-śṛṅgāra. In contrast the ‘love’ which Rāvaṇa professes towards devī Sītā does not become rasa. It's a fallacious appearance or semblance of rasa i.e. rasābhāsa. Since it manifests in the form of lust towards a married woman it is indeed rasābhāsa. Likewise any sthāyibhāva which shows up in inappropriate places becomes rasābhāsa.

The utsāha (enthusiasm) which Śrī-rāmā shows during the killing of the rākṣasas Khara and Dūṣaṇa, or the same emotion which Śrī-rāmā and Lakṣmaṇa during the events of the yuddha-kāṇḍa when they fight their enemies manifests as vīra. If they show anger then it manifests as raudra. Examples of karuṇa include the laments of Tārā after Vālin is killed and the lament of Mandodarī after Rāvaṇa is slain. The examples of adbhuta can be seen in the bridging of the ocean and the crossing of the ocean by Hanumān. The fear expressed by the rākṣasīs after the island of Laṅkā is burnt leads to bhayānaka. Bībhatsa is present in the conduct of Kuṃbhakarṇa. These are just a few examples. One can find many such instances reading the work.

The hāsyarasa

The sthāyibhāva of hāsyarasa i.e. hāsa is a mood. It leads to the expansion of our mind. The emotion is expressed mainly through laughter. This is the anubhāva of hāsa. The inherent mood of hāsa present in the person indulging in hāsya shows up as laughter. This same mood and expression manifests in the sahṛdaya due to the refinement or saṃskāras. Since the audience becomes one with the comic character and enjoys the comedy they also experience the same emotion. Laughter is divided into categories based on the attributes and nature of the audience and entity which is the target of hāsya. It sometimes manifests as just a smile which is called smita or mandahāsa. Sometimes it manifests as a loud laugh which is called aṭṭahāsa. Laughter is classified into smita, hasita, vihasita, prahasita, atihasita - and so on. Mostly in the characters belonging to the class of dhīrodātta (magnanimous and valourous characters) only smita is normally found.

This is the second part of the multi-part translation of the Kannada book "Valmiki Munigala Hasya Pravrtti" by Mahamahopadhyaya Vidwan Dr. N Ranganatha Sharma. Thanks to Dr. Sharada Chaitra for granting us permission to translate this wonderful work. The original in Kannada can be read here