Do Indians have a sense of history? No, says the received wisdom even today in major sections of the academia and the media. If you as much as question the sources, the roots of this received wisdom, you are branded with the choicest of Leftist labels but that’s the least of our concerns.

Before looking at a “sense of history” or “historical sense,” we need to look at how history is defined. Commonly accepted definitions include:

- A study of the human past.

- A field of research which uses a narrative to examine and analyse the sequence of events, and… attempts to investigate objectively the patterns of cause and effect that determine events.

- Historians debate the nature of history and its usefulness. This includes discussing the study of the discipline as an end in itself and as a way of providing “perspective” on the problems of the present.

Digging a little deeper, we find the following information related to how history is commonly understood today:

- The stories common to a particular culture, but not supported by external sources….are usually classified as cultural heritage rather than the “disinterested investigation” needed by the discipline of history.

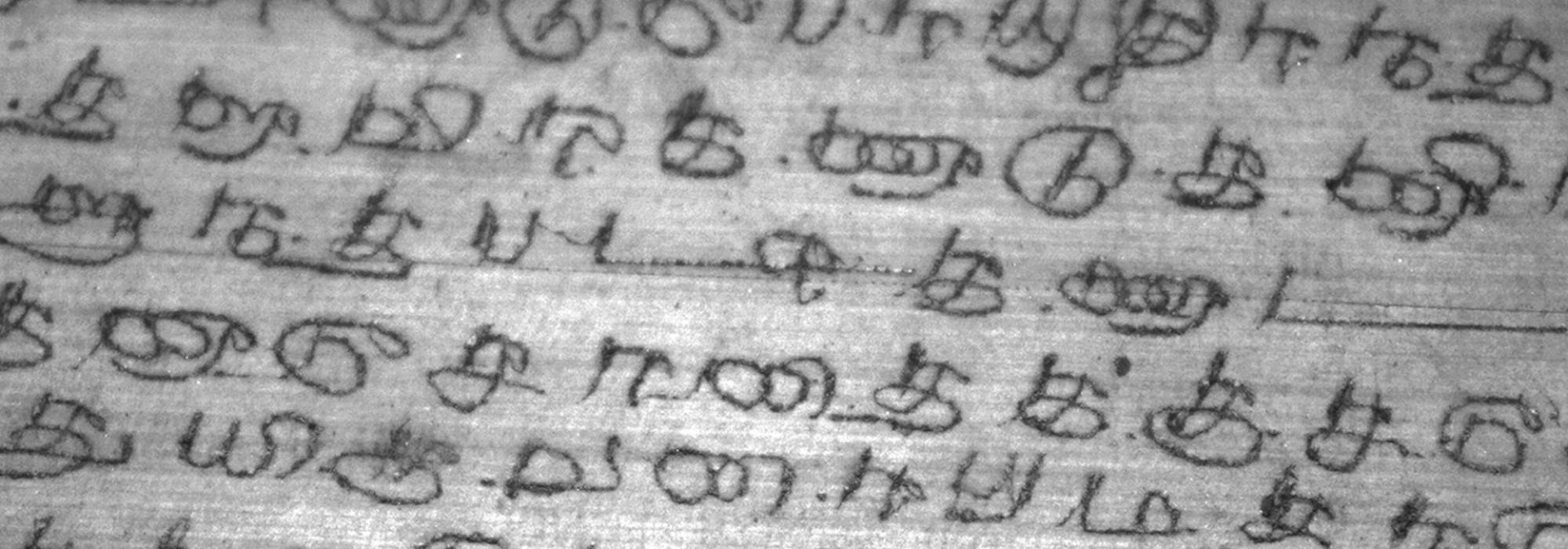

- Events of the past prior to written record are considered prehistory.

Based on these, we can arrive at the following:

- The advent of writing plays a major role in our definition of history.

- The oral tradition, however authentic, however well-preserved is kept beyond the definition of history.

- All oral traditions occurring even after the advent of writing aren’t considered as historical evidence.

- History and/or history-writing is essentially a disinterested, academic discipline.

This conception of history is laudable for its scientific approach to studying the past destinies of civilizations, nations, and indeed, the whole world. And this conception is a product of a mind that has a linear view of time. Thus, today’s newspaper is tomorrow’s history, which fifteen years later, finds its way into textbooks. History then is a little more than a diary without a last page, populated with names, dates, and places and how the three play out with one another.

While this precise, factual approach to history has yielded us worthy insights it has made history largely a boring subject. It is the one subject uniformly hated by most starting from primary school up to educated adults who dismiss history in terms of “who wants to know what Julius Caesar did in 62 BCE?” You can blame our education system or whatever but it’s undeniable that reading this sort of chronicle is boring however factual it may be.

But then the same people who despise reading history enjoy reading historical fiction, which continues to command a great deal of popularity. The reason isn’t difficult to fathom: entertainment naturally appeals to the human psyche. And people, when they buy historical fiction, are motivated primarily by the fiction element in it. Julius Caesar becomes a character in a novel first; that he was a powerful Roman emperor who actually existed is secondary. In the end, what the novel accomplishes–like most good literature–is that it entertains the reader, who without his knowledge has also learnt a lot of history about Julius Caesar, the Roman Empire, the geography of 1st Century BCE Europe, military equipment, battle styles, and architecture among others.

In other words, history from being a mere fact has been transformed into a value, to recall the words of the venerable M. Hiriyanna. To draw from Hiriyanna’s example, water is a fact as is thirst. When you elevate the act of quenching the thirst of a person to a virtue, the two facts are transformed into value. In much the same way, when a dry set of facts–dates, people, places, circumstances, and situations–are woven into a narrative richly intermixed with fundamental human impulses, fact becomes value.

Itihasa and History

In the Indian parlance, this is called Itihasa. The common Indian-language equivalent of the word “history” is Itihasa, which, though accurate, is also incomplete. The Sanskrit Itihasa can be split as Iti+ha+aasa, roughly translated as “This is how it happened.” The key word is “how.” The exact date of the events is insignificant. The immediate emphasis is on the “value” rather than the “fact” aspect as we shall see.

In India, only the Ramayana and the Mahabharata are termed Itihasa. No chronicle of any royal lineage or descriptions of great battles, charitable and public works and suchlike, which came after these two epics were given this title.

What’s more interesting is how these two epics (synonymous with Itihasa) are typically “read” in India. They’re recited, not read, mostly on a regular basis with commentaries and explanations accompanying the recital. It is not uncommon even today to find a speaker well-versed in these epics to recite them–musically on numerous occasions–verse by verse, stopping after each verse to explain and elaborate its meaning, significance and so on. As far as I know, no other country reads and/or recites its history in this fashion. Even if these epics are stripped of the much-derided “religious” aspects, they’re still recited exactly the same way I described. The reason again, is because Ramayana and Mahabharata are not mere chronicles of royal dynasties and events but something far beyond and far elevating.

The Indian approach of viewing history as a value is rooted in the Indian conception of time as cyclic. And thus it doesn’t matter whether Krishna lived exactly 5016 years ago or 5 minutes ago. Indians can summon their history at will. The past, present, and future all exist now. All it needs to bring Krishna alive is to stage an impromptu street-play on say, the episode of Sudama to show how he valued friendship. Or the wealthier of the lot can simply build a temple with carvings that depict his life. Or we can simply announce that we’re celebrating the wedding of Rama and Sita. Each time you read/hear that someone slept like Kumbhakarna, you are recollecting a tidbit of Itihasa. The Rama Navami and Krishna Janmashtami are not mere festivals: they’re also how we recall our history. In other words, India has universalized history by personalizing it, by making it dear to every person who reads it. And this is exactly why and how we’ve managed to preserve our history intact over thousands of years.

One outcome of a cyclic view of time is the hope that it gives. When human (and animal) life is impermanent, ancient India embarked on a quest to seek the permanent, which eventually led to the flowering of Vedanta, which in turn branched out to give rise to various knowledge streams including the arts. Because it’s impossible for anyone to actually “see” the “end” of time, Indians were able to perfect the concept of sanatana or Eternal. Prosperity, happiness, wars, destruction, and death became mere punctuations in an ever-turning wheel of prose.

The Ramayana and the Mahabharata are enduring because they contain this underlying concept. And they offer whatever the seeker seeks. If a Rajaji gives us a wonderfully abridged version of the Mahabharata, a Mallika Sarabhai seeks to “deliver” justice to a patently evil Shurpanakha. They will continue to survive and inspire because they not only embody eternal values but strum the strings of the most fundamental human impulses. Why else would a barely-educated villager know the Ramayana and the Mahabharata by heart when it doesn’t earn him bread but doesn’t mind not knowing what happened in 802 CE?

Comments