Hinduism is the major religion of India with a worldwide following of over a billion people. In its original and purest form, it is a sanatana dharma (loosely translated as ‘eternal truth’ or ‘timeless religion’) that represents at least 7,000 years of contemplation, tradition, and continuous development in India. One who follows Hinduism is called a ‘Hindu’ (the term originally referred to a person who lived beyond the Sindhu river, i.e. in undivided India).

Hinduism has no single founder. Many ancient seers and sages, both men and women, contributed to its foundational contemplations, conceptions, texts, philosophy, the corpus of all of which can be embodied as “Hindu scriptures” as distinct from the well-known meaning of the Christian Scripture. Hindu scriptures are numerous and diverse. Most of them are written in the Sanskrit language. Sanskrit, like Latin, is the root language for several languages and both belong to the same language family.

The word ‘scripture’ comes from the Latin scriptura, meaning ‘that which is written’ (thus also the strict adherence to what is written). The equivalent terms in Sanskrit for Hindu scriptures are Shruti, ‘that which is heard’ and Smrti, ‘that which is remembered.’

Rishis (the seekers of truth, seers) of ancient India contemplated on creation, human nature, refining base instincts, purpose of life, workings of the physical world, and the metaphysical dimensions of the universe. The collective consciousness of the rishis is called veda. The literal meaning of the word veda is ‘to know’ or ‘knowledge.’

Vedas are the foremost revealed scriptures in Hinduism. Every Hindu ceremony from birth to death and beyond is drawn from the four Vedas: Rigveda (consisting of riks or verses), Yajurveda (consisting of yajus or prose), Samaveda (consisting of samans or songs), and Atharvaveda (consisting of sage Atharvan’s compositions). These comprise the shruti texts (or rather, the ‘compositions’ that are collectively called shruti). Though any body of knowledge can be called a Veda, like Ayurveda (body of knowledge dealing with health), the term shruti applies only to the four Vedas.

The rishis taught this collected wisdom to their disciples, who in turn taught it to their disciples. Thus, this knowledge was passed on, intact, for several generations without a single word being written down. Even today, traditional students learn the Veda orally from a guru (teacher). A verse from the Rigveda Samhita (10.191.2) poignantly captures the intellectual atmosphere of those times:

सं गछध्वं सं वदध्वं

सं वो मनांसि जानताम् |

देवा भागं यथा पूर्वे

संजानाना उपासते ||

Come together, speak together,

let your minds be united, harmonious;

as ancient gods unanimous

sit down to their appointed share.

The final portion of the Vedas, called ‘Upanishads,’ contains anecdotes, dialogues, and talks that deal with body, mind, soul, nature, consciousness, and the universe. Of the several Upanishads, ten are typically considered to be prominent: Isha, Kena, Katha, Prashna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, and Brihadaranyaka.

Post-Vedic texts form another set of scriptures. These are the smrti, composed by a single author and later memorized by generations. The term smrti is also used while referring to the dharmashastra texts in general and to the works of Manu, Parashara, Yajnavalkya, et al. in particular.

The smrti texts include the Ramayana and Mahabharata (the epics), Ashtadhyayi (grammar), Manusmrti (law), Purana (old episodes, typically known as mythology), Nirukta (etymology), Shulba Sutras (geometry), Grihya Sutras (rules and doctrines governing family life), and a whole body of texts governing architecture, art, astrology, astronomy, dance, drama, economics, mathematics, medicine, music, nutrition, rituals, sex, and warfare, among others. The Bhagavad-Gita (or simply ‘Gita’), which is a small part of the epic Mahabharata, is an important and widely read scripture of Hinduism. It is one of the most comprehensive summaries of Hinduism.

The Sanskrit word for Creation is srishṭi, which means ‘pouring forth.’ It is not ‘creation’ but rather an outpouring, an expansion, a change. The idea of creation is discussed in different ways in the Vedas. One hymn (Nasadiya Sukta) proposes a brilliant conceptual model for creation while another (Hiranyagarbha Sukta) raises and answers many questions about god and creation. Yet another hymn (Purusha Sukta) describes in detail the process of creation. Amidst all these varied views is a single underlying idea: ‘one became everything.’

Another contention is that the concept of god is subsequent to creation. Hinduism has many gods (or ‘deities’) but only one supreme spirit. The Vedas make a clear distinction between God (Deity) and Brahman, the supreme spirit, which is beyond all creation and destruction. According to the conception of god in Hinduism, god can either have a form or can transcend form. Among the gods with form, there are many varieties; gods can be male, female, half-male and half-female, or can take the form of various animals, birds, mountains, trees, planets, stars, and other elements of nature.

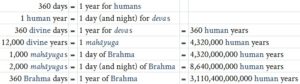

The Hindu timeline spans trillions of years and time is considered cyclical rather than linear; so we have eternal time cycles one after the other with no beginning or end. The Surya Siddhanta, a treatise of Hindu astronomy explains the staggering timeline:

...twelve months make a year

this equals a day and night of the gods (1.13)

360 days and nights of the gods make a divine year (1.14)

12,000 divine years make one mahayuga. (1.15)

A day of Brahma spans 1,000 mahayugas

a night of Brahma also spans 1,000 mahayugas. (1.20)

Brahma’s life span is 100 Brahma years. (1.21)

A mahayuga (Great Age) is made up of four yugas (Ages): Satya yuga, Treta yuga, Dvapara yuga, and Kali yuga. In human terms, a mahayuga is 4.32 million years. A day of Brahma (the Deity of creation), spanning a thousand mahayugas equals 4.32 billion human years, which is the time he is active and thus enables activity in the universe. This period is called a kalpa (cosmic cycle). During the night of Brahma, all creatures are dissolved only to be brought forth again at the beginning of the next day (i.e. the next kalpa).

The notion of space is similarly enormous in Hinduism. Traditionally, the universe is divided into three realms – earth, sky, and heaven, but there are other kinds of divisions of space. The Mahasankalpa, one of the traditional texts on ritual, talks of fourteen worlds in the anantakoti brahmanda (the infinite cosmos) – seven above and seven below, with the middle one being the earth. On earth, it identifies seven dvipas (islands); each dvipa is divided into nine varshas (subcontinents); each varsha is divided into nine khandas (provinces). It also mentions ten forests, thirty-five rivers (seven main rivers with five tributaries each) and several mountains that are found in India (jambudvipa, bharatavarsha).

Hindu sects are many and they often follow their own set of traditions and customs. While they seem very divergent, they have an underlying unity. Hinduism has a lot of freedom and openness with regard to beliefs, practices, and philosophies of its followers. For example, of the belief in god: some Hindus believe in one god while some others believe in many; some believe in god with a form, others in a god who transcends form, while still others are agnostics.

Fundamental Hindu values include harmony, tolerance, righteousness, respect for nature, and respect for the (unseen) supreme. Hinduism accepts other religions and modes of thought and worship. Here are two verses from the Rigveda Samhita that bring out these values very nicely:

आ नो भद्राः क्रतवो यन्तु विश्वत्व्

अदब्धासो अपरीतास उद्भिदः |

देवा नो यथा सदमिद्वृधे असन्न-

प्रायुवो रक्षितारो दिवे-दिवे ||

May noble thoughts come to us from every side,

unchanged, unhindered, undefeated in every way;

May the gods always be with us for our gain and

our protectors caring for us, ceaseless, every day.

(1.89.1)

इन्द्रं मित्रं वरुणमग्निमाहुः

अथो दिव्यः स सुपर्णो गरुत्मान् |

एकं सत् विप्रा बहुधा वदन्ति

अग्निं यमं मातरिश्वानमाहुः ||

They call him Indra, Mitra, Varuna, Agni;

he is the divine, winged Garutman.

The truth is one; the wise call it by different names:

Agni, Yama, Matarishvan.

(1.164.46)

The Hindu worldview emphasizes conduct more than creed and individual realization of truth is placed above dogma. Thus the contention that one need not read the Vedas to know the Vedas. Further, there is a notion that knowledge has to pertain to time and location (every kalpa has its own Veda and every province has its own rules). The spirit of the Vedas will remain the same but the form will keep changing. A practical manifestation of this notion is the freedom to add a khila sukta (interpolations/additions of verses to the original) the Vedas. These khila suktas – Sri Sukta for example – are later additions done to the Vedas to ensure that it remains relevant for the times.

Hinduism celebrates the diversity of existence and embraces the world as part of a big family, as recorded in an ancient book of stories, the Hitopadesha:

अयं निजः परो वेति

गणना लघु चेतसाम् |

उदारचरितानां तु

वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम् ||

“These are my own, those are strangers” –

thus the narrow-minded ones judge people.

But for those magnanimous hearts,

the world is but one family.

(1.3.71)

The Vedas call humans by a cheerful and hopeful name – ‘the children of immortal bliss’ (Rigveda Samhita 10.13.1). We are born pure and perfect but over time we accumulate the dust of unhappiness and pettiness. The constant quest is to return to our true nature as children of bliss. A prayer from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad talks about the spiritual journey from ignorance to illumination:

असतो मा सद्गमय |

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय |

मृत्योर्मामृतं गमयेति ||

Lead me from falsehood to truth,

lead me from darkness to light,

lead me from death to immortality.

(1.3.28)

Hinduism is perhaps the oldest, most diverse, and most sophisticated system of philosophical and religious thought and practice, covering nearly everything that comes under the umbrella of religion and philosophy. A human lifetime is insufficient to exhaust the wisdom it has to offer, and accessing even a small portion of this vast treasure enthralls, enriches, and elevates.

Co-written by Hari Ravikumar.

Adapted from the introduction to The New Bhagavad-Gita. Thanks to Shatavadhani Dr. R Ganesh for his review and astute inputs. Thanks to Sandeep Balakrishna for his wonderful edits.

Comments