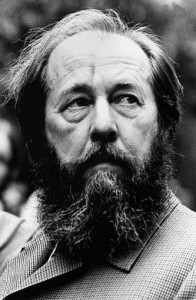

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the Nobel Laureate (1970, for literature), is one of the eminent writers of Soviet Russia of the twentieth century. Although he won the most coveted Noble Prize he was expelled from the USSR’s union of writers, and he was denied the use of state archives and libraries. Besides, Solzhenitsyn was ostracized by Soviet officialdom. The then Russian government did not permit Solzhenitsyn to receive the Nobel Prize. Luckily, Solzhenitsyn had already left for the United States of America by the time the Prize was announced. He was on exile in the US for a long time and we may recall that only during Mr. Gorbachev’s regime he returned to Russia. Again we may remember that another eminent writer Boris Pasternak was also not allowed to receive the Noble Prize (for Dr. Zhivago) by the then government.

Solzhenitsyn's works raise poignant questions about the contemporary political systems, use or misuse of scientific achievements by the power managers and the need for the ethical standards and values in our changing modern society. His writings evince a unique insight into human psyche, that is seen in the writings of Dostoevsky, that plunge into the depth and into the very naked souls of human beings. But unlike Dostoevsky – who sentimentalizes – Solzhenitsyn intellectualizes the problems and emotions. Perhaps this is the dominant feature of modern writers of the twentieth century. They are more cerebral. There we witness love, compassion, sympathetic understanding, sense of rootlessness and a sense of belonging too with the daring non-regretting acceptance of the reality in its totality. No sugaring of the bitter pill nor escapism. We cannot find the characters of either Dostoevsky or Dickens in Solzhenitsyn. Perhaps this is due to the technical progress and prosperity that has resulted in failure of communication – personal communications – or it is due to the disillusionment, frustration, and cynicism that the wars have imposed. Especially in Solzhenitsyn, it might be due to the then political system with the iron curtain and curb on individual freedom.

Solzhenitsyn’s doctrines are well mirrored in his works like Cancer Ward, August 1914, Candle in the Wind, The First Circle, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, and many others. Like the work of Albert Camus, Franz Kafka, John Steinbeck, and Arthur Miller, Solzhenitsyn's works too stress the need of individual responsibility, individual morality, social awareness, and a keen ethical sensitivity. Solzhenitsyn states that yearning for inner progress and perfection should stir within the soul of man and cannot be imposed from outside. No amount of scientific, technological achievements can help a man in this field. And this “perfecting the structure of the soul” is to be achieved individually and may not be possible to achieve en masse. Collective achievements, no doubt, our possible – and even essential – in the fields of agriculture, industries, education, medicine and other scientific researches, where strict maintenance of external discipline can work wonders. But in “perfecting the structure of the soul”, the striving should be by the individual himself. These concepts are presented in many of Solzhenitsyn’s works.

In a reply to three students (in 1967), Solzhenitsyn writes that he believes in “two related innate human feelings – a personal conscience which prompts man in his dealings with other individuals: and a personal sense of justice which prompts him in his attitudes towards society.” He asserts, “Justice exists if there exist just a few who feel it.” And the characters like Alex, Alda, Aunt Christine and others redeem their society just by feeling justice. Candle in the Wind reflects Solzhenitsyn’s professional background as a mathematician and his interest in science and technology. In The First Circle, he is concerned with the misuse of scientific research under Stalin’s totalitarian regime.

Candle in the Wind reveals anxiety and fear of a rational human being about the consequences of rapidly increasing technology in science especially in the field of medicine and biotechnology on our society – especially the consequences of the experiments like human cloning, bio-cybernetics, neuro-stabilization, etc. The outcome of these experiments will be more dangerous in the hands of the power politicians than nuclear weapons. This danger of the misuse of technology by self-seeking unscrupulous technocratic elite is the major preoccupation of Solzhenitsyn. There are scientists like Philips and Sinbar who consent to pledge their talents at the service of a totalitarian state, which readily provides them unlimited funds and powers. In this play, through the character of Philip, Solzhenitsyn exposes the type of scientists who rationalize their careerism. Alex, the main character of the play, gives expression to Solzhenitsyn’s faith in the primacy of individual conscience. Alex maintains that man’s first duty on earth is to live in accordance with its promptings, which are determined by the principles of absolute morality. But in our century of the steel and the atom, of space, of electric power, and cybernetics it is especially difficult to heed that stupid inborn feeling. Yet Alex persuades Alda to undergo the operation, a surgery of neuro-stabilization. Alex does this because his awareness of the “internal moral law” has now been blunted by the rationalism and materialism of his new environment. He ignores Aunt Christine’s injunction to “heed the light that is in thee.” He finds in Alda that spirituality which he prizes above all else. The society in which she lives needs idealists and non-conformists and not stabilized automatons. Alex destroys her in his arrogant belief that it is his duty to make her personality conform better to this society, without the rationalistic justification of Philip or Terbolm and interferes with the “most perfect thing on earth – another human being”. This surgery is not shock-proof. Though the operation stabilizes the emotions in Alda, her father’s health shatters this stabilization. She cannot endure this agony, stress, and sorrow. She wants to return to the stabilized condition for “she had felt so calm then,” but Alex refuses to consent to the second operation on Alda. Alex is isolated; he perceives that it is his responsibility to defend the individual human spirit against onslaught of dehumanizing forces like Philip’s bio-cybernetics and Terbolm’s social cybernetics. Individuality is not hedonism and ruthlessness but selfishness and humility. Alda is the flickering candle and Alex wishes to defend her and it seems to convey a profound pessimism about the future of man in modern society. Yet in his apparent competence Alex never loses human regeneration. He thinks “man is called upon to perfect the structure of his soul” and spiritual obligations must be fulfilled even at the cost of indifference to grandiose projects for the reform of human institutions. In the play, once Uncle Maurice is shocked to see that Alex has to use candles for lack of electricity. And to the queries of his uncle, Alex retorts, “Did Plato have a battery? Did Mozart have 220 volts? In candle light your heart opens up.”

The second danger that Solzhenitsyn foresees is the technocratic elite using the power and technology to create an ideally regulated society, and this will destroy individuality and variety. Solzhenitsyn rejects Terbolm’s belief that science can complement man’s conscience and has claim that social cybernetics is not processing of millions of people, not an onslaught on people’s souls. Solzhenitsyn criticizes the belief held in Soviet technocrat circle that an ideal society can be built on the cybernetic principles "one hundred percent accurate information, co-ordination, and feedback" (Terbolm’s dogmas). Terbolm's pyramidal model of totalitarian society is inefficient, for it lacks these features, particularly feedback. Terbolm's “electric Leviathan” of an ideally regulated society is just as unacceptable as Philip's neuro-stabilization. Both imply, ultimately, the destruction of human soul. So they are rejected. The gravest consequence of the workshop of science is the readiness it encourages in mankind to place its destiny in the handle of technocratic elite.

Cancer Ward is as symbolic as that of Camus's The Plague. Each character in the novel is affected by and infected with some or other type of cancer. The “Cancer Ward” is Russia in miniature and it may be the whole universe also. We may notice the absence of any article (‘a’ or ‘the’) in the title. It is merely Cancer Ward. The characters of the novel represent Solzhenitsyn’s contemporary political situation, politicians, party people, poets, students, researchers, self-seekers, and idealists. There are people who are in exile, and there are "men inside the country – “a certain percentage who managed to survive” – and who live in an atmosphere of fear and darkness." The two characters of the novel, Oleg Kostoglotov and Aleksei Shulubin respectively present the experiences of an exile and a man inside the country. The discussion between these two analyses the then current political isms and dogmas and throws light on the merits and demerits of the same. Shulubin discards democratic socialism as simply superficial. According to him, even an “abundance of material goods cannot build Socialism,” because “people sometimes behave like buffaloes," "they stampede and trample the goods into ground.” Moreover, social life cannot be built on hatred, so you cannot have “socialism that is always banging about hatred.” During the course of these discussions Solzhenitsyn uses a phrase, perhaps new coinage “ethical socialism”. The concept of this ethical socialism is nearer to Gandhiji’s concept of politics. According to Solzhenitsyn, “In ethical socialism all relationships, fundamental principles and laws flow directly from ethics – and from ethics alone.” Further he states that even scientific research should be conducted on the basis that it does not damage the basics of morality. This concept of explicitly expounded in the play Candle in the Wind and The First Circle. Tampering of the scientists with human nature ultimately creates chaos only. Solzhenitsyn feels that even the foreign policy of a country should be based on ethical sense only. The essence of Solzhenitsyn's ethical socialism consists in these words, “If we share things we don’t have enough of, we can be happy today.” These very simple words, hidden with a magnificent meaning, are a plea to humanity for mutual trust, love, compassion, and understanding. For none can share what he has not enough of with others, unless there is love, affection, and empathy. This maxim, “Share the things we don’t have enough of,” is a realistic or practical approach of elevating human values, without idealizing or glorifying or sentimentalizing or giving it a religious aura. Jack London’s statement (in one of his stories or essays) supports this idea, “A bone to the dog is not charity. True charity is the bone shared with the dog, when you are as hungry as the dog.”

Jack London’s concept of charity and Solzhenitsyn’s concept of ethical socialism reminds us of the story of a mongoose in the Mahabharata. Maharshi Vyasa, in that story, clearly indicates the difference between charity and the shows of charity and the pride behind charity, generosity, and donations. Dharmaraja completes his Rajasuya-yaga and millions of people are dining there. The water with which they washed their hands flowed like a river. Even a person like Dharmaraja felt a sense of pride or ego. Lord Krishna stood by Dharmaraja and he understood Dharmaraja’s mind. He wanted to teach him a lesson. At that moment, a mongoose was seen writhing in that water. The mongoose again and again looked into his body and sight it had not turned into gold, for half of the body of mongoose was already gold, even before he came here. When asked by Dharmaraja, the mongoose told the story of a poor brahmana and his family living in forest. The family could not get a square meal a day yet they would feed a hungry guest and prefer to starve themselves. One day they had prepared four rotis with great difficulty. They were ready to eat and a hungry guest came. One by one, the master, his wife, son, and daughter-in-law parted with their share and only then was the guest satisfied. The water in which that one guest had washed his hands, had turned half the body of the mongoose into gold. With great expectation, the mongoose had come there, for millions had dined; surely his body would fully turned into gold. But he was disappointed that the miracle did not happen. This is how the seer Vyasa pricks the pride of Dharmaraja and comments upon the vanity and pompous show of charity.

Solzhenitsyn writes that history has rejected capitalism "once and for all,” and “capitalism was doomed ethically before it was doomed economically, a long time back.” According to his maxim, one should never direct people towards happiness, because happiness too is an idol of the market place. Instead, one should direct them toward mutual affection. A beast gnawing at its pray can be happy too. Happiness is a mirage, and ideas of happiness have changed too much through the ages. When we have enough loaves of white bread under our heels, when we have enough milk to choke us, we still won’t be in the least happy. But if we share things we don’t have enough of we can be happy today.

Another great novel by Solzhenitsyn, August 1914, explores the effect of war on human mind and human society. Wars demoralize human spirit, and human values are jeopardized by wars. The novel beautifully depicts the conflict between the innate moral law and the hankering for material possession of ill-gotten treasure, in the minds of soldiers. In spite of the spiritual aversion for the ill-gotten treasure, with an ironic logic, the soldier-man is compelled to make a sad compromise with the order of things. The Brigade Commander Yaroslav, a man of ethical values, is a good example of this. There were so many exhausting days on short ration. His men-soldiers were hungry. If they slip away in response to the gnawing urge of hunger, should they be punished? His men were looting in the abandoned property. When Yaroslav chides them, one of them retorts that there was nothing to be ashamed of. If they should fight better, they should be fit, the army needs them fit. Logically justifying the action he advises Yaroslav to get a sweater for himself. This logical justification of loot, inefficiency of the army, primary urges of man and to gratify them legally or illegally sicken him. He suddenly feels an aversion against all material comforts. He no more feels hungry and thirsty. The helplessness of the soldiers, their greed to possess the material things that are scattered unprotected, and the uncertainty of a soldier’s life in war sickens this idealist. Yet he thinks his men will not misbehave. When the best soldier, who was the pride of the platoon, runs away with a bundle, Yaroslav is disillusioned. And this spreads like a plague. Yet when he sees his soldiers, eating, drinking happily and offering drink to him – their loved officer – with childlike enthusiasm and competition, he could not even refuse the drink. A lump comes into his dry throat. Then he takes a gulp of cocoa. This is the sad compromise that happens everywhere.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is a kind of prison literature, which poignantly shows the prominence of food – the first primary need – in the life of a prisoner. The anxious waiting of prisoners, for a small loaf of bread, a bowl porridge and their delight at having an extra pair of boots are worth reading. Even in the adverse condition of prisons the prisoners' zest for life, their belief in human nature astonishes. To them, work was like a stick. It had two ends; "when you worked for the knowing you gave them quality, when you worked for a food, you simply gave him eyewash.”

Solzhenitsyn's works stress the need to preserve the flickering flame of the candle with care and concern. This flame – the candle, that is the human soul is facing the double storms of science and technology and dire inhumanity. A whiff will blow it off, why need steel, rope, stone and bombs? We must remember Raimon Panikkar’s words, “The splitting of an atom is opening the womb of nature. It is a cosmic abortion of catastrophic proportions.” (Quoted from an article in Articulations, Sunday Herald.)

Comments