One of the fascinating things about travelling across India especially on our national highways is the sheer number of milestones of history, seemingly casually erected so elevated and steep that one is compelled to pause or stop and listen to their stories. We’re reminded of the scene in Dr. S L Bhyrappa’s Aavarana where Razia (or Lakshmi) mulls at a train station about visiting the temples destroyed in the vicinity and learning all about their tragic histories.

Nijagal is one such historical milestone. Known today as “Hale Nijagal” (Old Nijagal), it lies just a few kilometres off Dobbespete on National Highway 4 running from Bangalore to Mumbai.

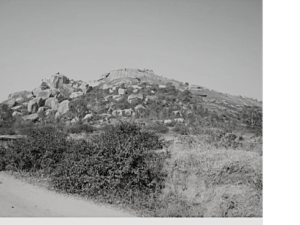

To our immediate sight, it’s clearly a majestic rocky mountain-fort that stares at our back miles after we’ve driven past it, like an imposing memory that repeatedly beckons us to it. But it is when we actually stop, and climb all the way to the summit of its august altitude that we tangentially realize the truth where Frost says,

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

[…]

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

View of the Nijagal fort from the base

The trek to the top costs about two hours depending on one’s fitness level.

At the top lie the heartrending remnants of a once-impregnable fort, the site of a historic battle won with a mix of strategy and raw, barbaric warfare.

The Battle for the Nijagal Fort

The latter half of the 18th Century witnessed a fierce power struggle between the Marathas, Hyder Ali and the British.

By then the Maratha Empire had long since transitioned into the hands of the Peshwas after the end of Shivaji’s short-lived dynasty. After the Maratha Empire had suffered a severe drubbing in the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761 losing vast swathes of territory, money, and prestige, it fell, as the aftermath of any defeat shows, into internal strife.

It was then that Shreemant Peshwa or Madhava Rao Peshwa I ascended the imperial Maratha throne and systematically began to reassert the Empire’s prestige and prowess. In February 1762, he set out to conquer Mysore—then under Hyder Ali’s regime—as well as the Hyderabad Nizam’s dominions.

The Maratha army under his leadership began an unstoppable, whirlwind expedition to wipe out Hyder Ali. Beginning with Adoni, Madhava Rao took Bellary, Kurnool, Devadurga, Rayadurga, Kolar, Bhairavgad, Devarayanadurga (near Tumkur), and reached Nijagal, en route to his final destination, Srirangapatana, Hyder Ali’s capital.

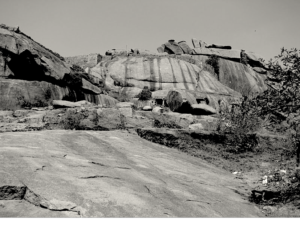

The Nijagal fort was built on the tip of this rocky mountain resembling an enormous, craggy semicircle of boulder placed atop it and decked in all directions with gigantic, slippery boulders, effectively sealing it off from assault of any sort. The altitude of the fort was beyond the reach of cannon fire. Physical scaling of the fort was rendered impossible—any such attempt would be met with a deluge of boiling oil and water and excreta from specially-constructed holes near the top of the fort.

A Burj or Bateri (an oval-shaped construction made of stone, sand and mortar and served as a watch tower) had military guards patrolling round the clock. A large, deep and wide fosse circumscribed the base of the mountain and was sprinkled with thorns. Crocodiles were bred in the moat at the base to add yet another layer of security.

More importantly, Nijagal was never in the danger of running out of water. Three freshwater mountain streams named Rasa Siddara Done (Done= pond), Kanchina Done (Brass pond), and Akka-Tangira Done (Sisters’ pond)–provided ample water supply.

The seige of Nijagal was a question of Madhava Rao’s personal and military eminence and one of survival for Hyder Ali. Hyder Ali’s morale like his treasury at that juncture was almost barren. Unexpected and successive thrashings and humiliations in the battlefield had pushed him into a desolate sanctuary in his palace at Srirangapatana.

This factor coupled with the confidence emanating from serial victories, was prominent in Madhava Rao’s decision to invade Hyder Ali and pick Srirangapattana like a cherry. However, none his earlier decisive victories in far stormier battles and under far tougher conditions had prepared him for Nijagal. His siege of the Nijagal fort lasted two months at the end of which he was thoroughly frustrated. Neither was his own condition getting any better. Madhava Rao I was left with a brother with one hand cut off, and his ammunition and supplies were perilously low.

At the time, the Nijagal fort was lorded over by Sardar Khan, Hyder Ali’s vassal. A shrewd and ruthless ruler, Sardar Khan had mercilessly stripped the region by hoarding enormous amounts of wealth in the form of money and produce, enough to last him for two years.

Enter Madakari Nayaka

It was then that Madhava Rao I requested Madakari Nayaka the Pallegar (Chieftain) of Chitradurga, for assistance. Chitradurga’s history is the stuff romantic, warrior-legends are made of. En route to Nijagal, Madakari Nayaka was moved by the remorseless rape of the entire region that spanned some 150 kilometers. The Maratha army had turned entire villages into smoking graveyards and charred prosperity.

Upon reaching Nijagal, Madakari Nayaka quickly reconnoitered the surroundings. His first break came when he discovered that the fort had two entrances for people to move into the town and back. These were the heavily-guarded Northern and Eastern entrances. His plan was as clear and as urgent. Because it was impossible to physically scale the fort during daytime without incurring massive causalities, he decided to scale it at night. But then his army regulars were ill-trained for the task.

His knowledge of the lay of the fort had also equipped him with the foresight to marshal great numbers of his loyal and special hunter-force that he had selected for the mission.

Indeed, the Nayakas (or Pallegars) of Chitradurga originally descended from hunter tribes that inhabited the mountainous and densely-thicketed regions of Chitradurga. Despite becoming Sovereigns Proper in later years, they never lost touch with their roots. They preserved and nurtured generations of fierce, fearless hunter-warriors for use in special occasions like this. These hunter-warriors were specially trained to impale fear deep into the enemy’s heart and camp alike. They used hideous camouflage, emitted blood-curdling war cries by producing a variety of beastly sounds, fought in the most daunting conditions, were expert mountain-climbers, and in general had no fear of death.

At nightfall, Madakari Nayaka’s hunter-warriors made a fire from dried wood not too far from the fort. By its light, they gorged on a heady diet of both roasted and raw meat which they gulped down with liquor and marijuana. Dinner done, they wrapped rugs on their bodies, dangled a rope made of fibre on their shoulder, and secured a bag comprising Giant Monitor Lizards around their waist.

When they reached the moat, they killed a couple of horses they had brought along, and threw the flesh into the moat to distract the crocodiles. They then dipped into the moat, swam noiselessly, locking their lips tightly together lest any poison in the water kill them, and climbed up the shore on the other side. They fastened the fibre rope to the feet of the lizards and flung the creatures upon the rocks.

Once the lizards’ grip was secure, they began a steady, swift, and noiseless ascent. In about an hour, Madakari Nayaka’s hunter-warriors were waiting in the pregnant darkness outside one of the two fort doors for their leader’s signal. Five hundred warriors had now surrounded the Nijagal fort from all directions.

After timing his response, Madakari Nayaka let out a shrill battle cry and led the charge from the frontline below. The guards that opened the fort door upon hearing the noise saw the hordes of death tearing forth towards them. Madakari Nayaka’s army of savage warriors instantly began colouring the silent night with a riot of blood and death. With their well-honed bestial yawling, the hunter-warriors tore the door open and chopped everybody in their path with their battleaxes. They sliced soldiers and non-combatants alike like leaves on a twig.

Madakari Nayaka’s surprise onslaught left no chance for Nijagal’s defenders to even realize what was happening much less respond to it. Heads and necks and hands and arms and fingers and legs flew. The ill-prepared Sardar Khan’s force simply watched itself being butchered indiscriminately. And after they had attained a bloody and decisive foothold, the hunter-warriors opened all avenues to Madakari Nayaka’s regular military force to enter the fort effortlessly.

Nijagal was awash with a continuous flow of fresh blood. While his hunter-warriors were busy slaughtering at will, Madakari Nayaka made his way to Sardar Khan’s bedroom, roused him from sleep, and engaged him in a man-to-man swordfight. It was an unequal contest: Madakari Nayaka was already intoxicated with the high of battle and was raring to slay more while Sardar Khan was struggling to shake off his slumber. More significantly, Sardar Khan could not fathom how his impregnable fortress could ever be breached. In one blow, Madakari Nayaka chopped off Sardar Khan’s hand, forcing him to surrender.

In the morning, Madakari Nayaka delivered Sardar Khan to Madhav Rao I.

Postscript:

Hyder Ali’s military successes owed to a combination of treachery, payout, cowardice, and luck. The defeat at Nijagal marked one of the all-time ebbs in his military career. However, Madhav Rao I died of tuberculosis a short period after he won Nijagal. The united Maratha Empire relapsed into internal discord giving Hyder Ali enough time and resources to systematically recuperate his losses and resurface as a major power in South India.

But he neither forgot nor forgave Madakari Nayaka, a mere chieftain who had mounted this humiliation. With the entire might of his force, Hyder Ali attacked Chitradurga in 1779, decimated it, threw him in the prison at Srirangapattana, and put an end to the Nayaka Dynasty.

Comments