Joint Endeavours

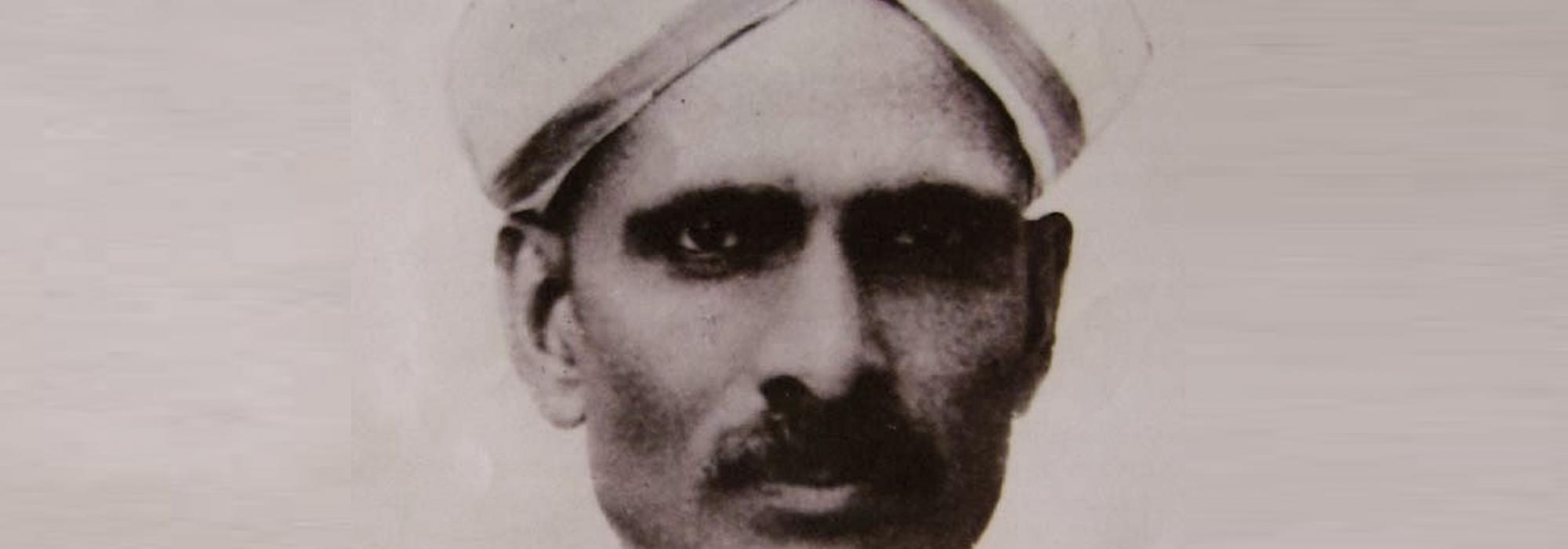

I have mentioned earlier about my first meeting with T S Venkannayya and A R Krishna Shastri. That was in 1915–16, just after the establishment of the Pariṣat. Even so, my friendship with Venkannayya became deeper only a few years later. He shifted his house to Shankarapuram sometime in 1920–21 perhaps. We would meet at least once a day. On so many occasions, we would spend half the day together.

At that time, my biography of Gopal Krishna Gokhale was to be reprinted. The arrangements were made at Power Press in Chickpet. We both would typically go there every morning at about eight. After proof-reading and correcting the drafts in the Press, our workplace shifted to K T Appanna’s Hindu Coffee Club or The Udupi Hotel. We would then return to the Press by around ten or ten-thirty. After completing our work there, we would return home.

Usually, our travel to and from my place would be on foot. The reason was our habitual chatting. During those days, perhaps there was nothing under the sun that we did not discuss or debate. On many occasions we discussed the characteristics of good writing. The written Kannada that was prevalent during those days had invited his scorn; he would say, “What’s this? It’s a huriṭṭu[1] sort of writing! It doesn’t have ‘weight’ – it lacks stuff. One can easily chew a bagful of it and digest it easily. The nourishment that the body gets is perhaps just as much as a gulagañji [red licorice seed] might provide! In a piece of writing, there must be respect and adulation for the subject matter. If what can be said in ten words is dragged on for a hundred, it might make the book bigger but won’t be useful to the reader.”

During those discussions, we would often critique the works of English, Sanskrit, and Kannada poets. Likewise, we would engage in discussions and debates related to Indian aesthetics, based on the treatises of alaṅkāra-śāstra like Dhvanyāloka [of Ānandavardhana], Kāvya-prakāśa [of Mammaṭa], Vakrokti-jīvita [of Kun-taka], and Sāhitya-darpaṇa [of Viśvanātha Kavirāja]. From Venkannayya’s thought process, I realised early on that he was a person of subtle and intense sensitivity.

Insight

He had an extraordinary insight into literature. One could call this ‘a feel for literature.’ ‘Feel’ suggests that one experiences it by touch. He had the acumen to fully grasp the subtleties and the essence of all that he merely touched. In a dark room, one’s ability to recognise an individual merely by touch can be called ‘feel.’ This might be a common experience for youngsters who frequent cinema halls. Likewise is the ability to recognise a person merely from the sound of his or her voice. That is ‘feel.’ Several insects and birds cognise the objects of their likes and dislikes merely by scent. This instinctive ability to smell and discern can be called ‘feel.’

In this manner, Venkannayya knew the quality of literature merely by its touch. Just by looking at a verse, or a line, or an episode, or from the utterances of a character, he could determine conclusively – “This is a richly emotional segment,” or “This is just meaningless sound,” or “This is just rambling,” or “This is delectable!”

After the demise of Prof. B Krishnappa of the Mysore College, there was a discussion in a friendly gathering about who should succeed him. At that point, the Principal of the college, Prof. N S Subba Rao praised the singular competence of Venkannayya and said, “He is a man with a feel for literature – a very rare type.” What he said was not an exaggeration but a statement of fact; I felt it then when he said those words; I feel the same even now.

Grasping the Essence of Poetry

During the time when the Sāhitya Pariṣat had undertaken the reprinting of Pampa-bhārata and the editing process was underway, every night Venkannayya would present himself at the appointed hour. That was because of the imposition of Prof. B Venkatanaranappa. Venkannayya would tolerate the professor’s fastidious nature by making light of it, with a smile on his face. Venkannayya’s keenness of poetic vision was apparent during that time. Which letter fits where, what sounds nice to the ears, what appeals to pronunciation, where the suggestive meaning is amplified, how to bring out the beauty in the literal meaning – he would seek and find such subtleties and patiently explain them. Sometimes, the work would get held up due to these mini-discourses. Even Prof. Venkatanaranappa, who was known for being a disciplinarian and was unyielding in matters of finishing the work within the stipulated period, also ended up relaxing his rules, forgetting himself in Venkannayya’s expositions.

Venkannayya was a person who had struggled in life, a man who underwent several hardships and had a firsthand experience of abject poverty. Therefore he was a patient and tolerant man. He wouldn’t have the heart to speak harsh words.

If people went to him with their difficulties, he would most certainly help them to the extent that was possible for him. He was not a person who ever experienced a period of wealth and luxury. Until he became a professor, his was a life of day to day existence – he lived one day at a time. In spite of this, there are several instances where he has helped people in need – I know this from personal experience. He stood as the guarantor at the bank for several people, thus helping them to secure loans. However, I am not aware of how many people remained grateful to him.

One morning, at about nine, Venkannayya and I were walking down Krishna Rajendra Road, towards Doddapete. When we came near Vani Vilas School, a man rushed in from a passage to our right and approached Venkannayya with an outstretched palm. His coat and dhoti were soiled and in tatters. His eyeballs were almost popping out and he had protruding teeth. Venkannayya searched all his pockets. He had nothing in his shirt pockets and elsewhere. He then asked me. Even I was penniless.

Venkannayya said, “I have nothing at the moment, Narasimhamurthy!”

“It doesn’t matter, sir. I just asked out of habit,” said Narasimhamurthy.

We proceeded further and had traversed about fifteen feet. We saw someone we knew. Venkannayya spoke to the gentleman and took a loan of half an anna; he then turned back, called out to the man who had accosted us, and said: “Murthy, take this.”

Narasimhamurthy said, “Why take so much trouble sir? You give me money every day! What if you don’t give it to me once?”

Venkannayya said, “It’s also a habit for me and I shouldn’t miss it.”

This is a testimony to the nature of Venkannayya – to feel empathy for another, to generously give, and to forget his charity without keeping any tabs. This was Venkannayya!

To be continued.

This is the third part of an eight-part English translation of Chapters 23 and 24 of D V Gundappa’s Jnapakachitrashaale – Vol. 3 – Sahityopasakaru.

[1] Refers to an easy-to-prepare sweet dish made from rāgi (a type of millet).