--- I ---

It could be reasonably argued that every nation that has attained and is characterized by an advanced stage of the post-industrialized democracy has killed artistic excellence in its truest sense. While a separate essay can be written examining this phenomenon, for the purposes of this article, it suffices to define artistic excellence as inherited classicism in the mold of ancient India, Greece, and Rome whose defining features include a deep and abiding love and reverence for truth, beauty, nature, language, patient contemplation, a sense of heroism, an exploration of eternal values, and above all, a sense of wonderment.

And it is precisely these that have been lost in the post-industrialized democracy where there’s nobody and nothing higher than the individual human being, who is now redefined variously as a component of an economic machine, a mere being “condemned to exist,” a mere consumer of material goods, and so on. The attendant consequences haven’t been entirely positive.

First, it has led to the near-elimination of society premised on the bedrock of the family unit as a value of societal sustenance and perpetuation even with all its various drawbacks. And over time, society, which had acted as a binding glue between individuals who had intuitively understood the value of adhering to some aspects of long-held traditions threw the baby out with the bathwater.

Second, when this happened, the societal and other environments that had sustained this classical tradition were also destroyed with the result that only a faint echo of classical learning exists in the West today. The other significant historical factor contributing to this destruction was the abject nihilism that enveloped the West post World War II.

But in India’s case, while the trajectory of this destruction has been different, the outcome has remained more or less the same owing to a toxic combination of mental and cultural colonization, and a society which continues to fight with itself.

But unlike the West, several aspects of our classical traditions in the artistic realm have been preserved in dance, drama, music, poetry, painting, sculpture, temple-building, literature, and learning because the aforementioned societal environment continues to exist in whatever depleted, or less-vigorous form.

---- II ----

It’s in this context that K Viswanath’s celluloid portrayals of the said traditions also become important. This is apart from the primary purpose of savouring his cinema for the sheer joy of artistic pleasure.

One of the most striking and defining aspects of Viswanath’s depictions of traditional, native, and rural society is the seeming effortlessness in showcasing rooted nativity with a subtlety that’s almost unmatched. When we contrast this for instance, with Kannada films made through the 1950s—70s decades, the portrayals of life in rural Karnataka are a childish mix of naiveté, loudness, good intent, and celluloid-sloganeering, it becomes clear that one can’t find better examples for Vachyata (explicitness) than these.

Of course, one can only hazard some guesses as to how he managed to hone his art with such élan.

For one, like most filmmakers, script writers, etc of his vintage, Viswanath had worked in his formative years in the truly Golden Era of Telugu cinema characterized by a rich classical milieu that drew from the best of traditional drama, classical Telugu poetry and continuous creative innovation in language usage and classical music. This era belted out one epic and mythological blockbuster after another ranging from Maya Bazar, Sri Krishna Pandaveeyam, Pandava Vanavasam, Lava Kusha, Nartanashala, Sri Krishna Tulabharam, Sri Krishnarjuna Yuddhamu, Bhakta Prahalada, Sri Krishnavataram…

For another, he was deeply rooted in that pristine Telugu cultural nativity found especially in the Guntur-Krishna-Godavari region with its vast and wealthy tapestry of temple traditions, rural beliefs, customs, family and social life, and folk arts. But more importantly, Viswanath intuitively grasped the pulse of the strand that united all of these: the traditional Hindu society of unknown antiquity. He combined these facets and gave them creative expression on screen in the precise idiom required to transform them into enduring works of cinematic art.

---- III ----

What is notable in almost all of K Viswanath’s movies is the manner in which he contextualizes his storytelling in a simple, traditional, and largely rural Telugu society and reflects the entire gamut of its travails, shortcomings, joys, beauty, and most importantly, its values as they unfold through the characters. Actually, “rural society” doesn’t fully reflect the emotional and experiential range couched in the Telugu word, “palleturu.”

Viswanath’s creativity lies in the fact that he never depicts one hundred percent of this society: he sets his story in a slice of the selfsame village life where people and not systems, are the prime focus and occupy the centre stage. This is an extraordinary strength and a superb storytelling technique that reveals itself when we briefly examine a few of his films.

Sankarabharanam

While Sankarabharanam tells the story of an intrepid and dedicated classical musician, Sankara Sastri, it’s set in the confines of a portion of a semi-village, semi-small-town. By progressively revealing even the minute aspects of his routine life—like bathing in the river early in the morning to teaching music to his young daughter immersed neck-deep in the river to his daily Puja, to his strict adherence to tradition but even going against it when some of its aspects militate against commonsense and humanity—Viswanath also reveals the larger society and interpersonal dynamics at play.

While this society has no problem accepting a prostitute in its midst, the full might of its self-righteous moral fury erupts when her daughter (groomed to follow in her footsteps) is seen with Sankara Sastri who gives her refuge in her troubled times. This society is much less agitated by her profession per se than its foregone conclusion that such a holy man has been defiled by her.

Indeed, nothing infuriates a society more than even the mere thought of an idol that it had worshipped just a minute ago, now fallen, now corrupted, the corruption occurring as a consequence of their own suspicious mindspaces. Indeed, our Dharmashastras reserve the harshest condemnation and punishment for a fallen Sanyasin. Sankara Sastri rapidly loses his stature in the community by way of social ostracism. But he miraculously regains his former social stature after she departs from his life: the fallen idol resurrected.

Sagara Sangamam

The same more or less plays out in say Sagara Sangamam in the sequences that hint at the community life and bonding reflected through the protagonist, Kamal Hassan’s mother’s character. Hailing from a nameless village, she’s an impoverished cook, part of a larger catering team of traditional cooks who eke out a living, often travelling to different towns and cities to cook at weddings and other large social functions.

Neither was this a mere team performing a professional task professionally: it was an extended family and a micro-community united by shared values, pain, little joys, culture, and customs. This important socio-cultural facet has become almost extinct and is replaced today by corporatesque catering outfits. It’s a testament to Viswanath’s art that he shows us the picture of that micro-community life mostly through conversations and a single scene at a wedding.

The Wedding Scene

https://youtu.be/R4BaCFUl7qU?t=10

Scene at the train station showing Kamal Hassan and his mother

https://youtu.be/VT10H4g-YCs?t=229

Swarna Kamalam

In Swarna Kamalam, Viswanath showcases yet another slice of a well-knit community of lower-middle folks set in the sleepy Vishakhapatnam of the 1980s. The only glimpse of the larger city we get is in the scenes fleetingly showing the protagonist Daggubati Venkatesh travelling across the city. This community lives in a world of its own, in an age-old chawl-like atmosphere where everybody knows everybody’s family secrets and difficulties.

The central plot narrates the story of an exceptionally gifted classical danseuse Bhanupriya, who should ideally continue her father’s legacy but is seduced by the mirage of a luxurious urban life, convinced that such “outdated” dance forms are useless coming as she does from the said lower-middle class background.

Viswanath’s choice of the aforementioned chawl-like setting to trace her journey from cynicism to discovering the joy in true art is commendable. The respect for her father’s artistic accomplishments emanating from within this community, from the vast numbers of the students he has trained in the wider world, is revealed through tiny flashes of dialogue, through quirks of the character of the devout Sri Lakshmi who thinks performing round-the-clock pujas and fasts is the route to have a baby, through the character of the violinist who’s in love with Bhanupriya’s sister and finally, through the character of Venkatesh who gently but persistently awakens within Bhanupriya an awareness of the value of the art she innately possesses.

Swati Muthyam

Swati Muthyam perhaps explores an intense sort of simple, rural community life and values given that it’s almost set entirely in a village. The whole movie is indeed a celebration of these facets.

More importantly, it’s a superb blend of a cultural heritage reflected through community and social practices, beliefs, customs, festivals, and traditions.

One of the most striking scenes is when the mentally challenged protagonist, Kamal Hassan ties the Mangalasutra (Taali) around the neck of the widowed female protagonist, Radhika in full view of the public during the sacred celebration of the festival of Sita-Rama Kalyana (wedding). While he gets beaten up for it initially by a largely orthodox rural society, they eventually honour the marriage because the Mangalasutra he has tied was originally meant for Sita mata, and so it shouldn’t be removed at any cost. But more fundamentally, it is sacred by its very nature: no matter who it is tied to, that lady automatically becomes a Soubhagyavati—as auspicious as Sita herself.

Viswanath’s artistic triumph lies in taking this tiny facet of an epic dimension and contemporizing it: this is a huge value in itself. Fused into this is the Rama Hari Katha song sequence that provides the backdrop that culminates in the said public “marriage.” Andhra Pradesh apart from Karnataka was home to the Hari Katha tradition for centuries. The picturisation of the song set to some superb lyric is also a testimony to Viswanath's creative vision. A widowed Radhika's face comes into full focus as she walks in while the lyric "DharAputri sumagAtri naDayADirAga" (As the Flower-like Daughter of Mother Earth walks about) plays in the background.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ts-Y5qr307E

Rama Kanavemira Song

This and similar values that infuse strength in dire straits are reflected for example, in the character of Nirmalamma, Kamal Hassan’s ripe old, destitute grandmother who derives her courage through abiding faith in Sri Rama and is endowed with an unshakeable conviction in traditional values, which she instills in Kamal Hassan quoting tidbits from the Ramayana, etc.

A particularly elevating scene is how the village doctor characterizes the mentally challenged Kamal Hassan as a “pure Yogi by birth” (https://youtu.be/QRv7LEtIL1I?t=379) who knows neither malice nor selfishness.

https://youtu.be/QRv7LEtIL1I?t=379

Scene where Kamal Hassan is described as a Yogi

It’s quite an extraordinary scene, an original artistic conception to describe a mentally challenged person as a Yogi, who the grandmother is fortunate to serve. Equally, in about a minute of screen time, Viswanath reveals a lot about the role such traditional doctors played and a society that was built around these values.

Saptapadi

In yet another landmark movie, Saptapadi, which deals with the subject of a ritualistic, traditional and orthodox Brahminical life and the “caste” problem, Viswanath fittingly places the action in a temple-centric setting in the countryside. What follows is a complex interplay of the conceptions of one’s own wife as Devi, individual and societal duties, and questioning of one’s own lifelong convictions.

Woven into this tapestry are some famous handovers of our cultural heritage. We can cite the creative use of Thyagaraja’s renowned Kriti, Marugelara O Raghava and the way the famous encounter between Adi Sankara and the Candala itself becomes the thought and the solution to the problem of inter-caste marriage vexing the protagonist Somayajulu’s mind. Equally, the classic rustic song sung by a cowherd boy, Govullu Tellanna Gopayya Nallana (The cows are white, Krishna is black) is a tour de force of sorts in establishing the crux of the film’s central theme.

What’s also noteworthy is the climax where when the protagonist Somayajulu finally agrees to the marriage of his granddaughter with a lower caste man, the background music, fittingly, is a Nagaswaram rendering of Thyagaraja’s philosophical composition, “Jnanamosagarada.”

--- IV ---

While volumes have been written about the nature of the relationship between society and art, it’s undeniable that art reveals itself through the medium of society and society is reflected through art, a sort of Advaita.

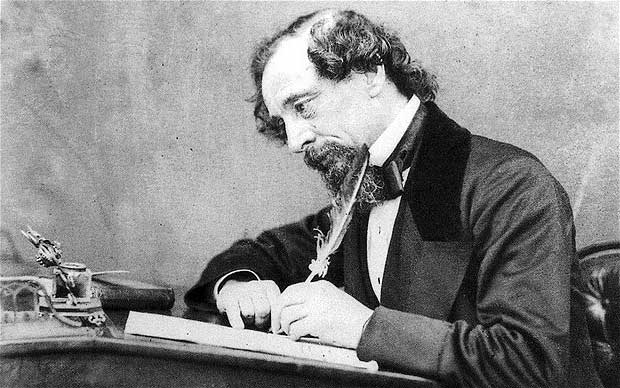

But truly enduring art using society as a medium, should transcend it. As an example, we can cite the work of say Charles Dickens, still considered as the father of modern novel. But Dickens didn’t rise above “superb” to “enduring” because he wrote copiously and passionately about a specific society and a specific period, which is no longer relevant or relatable. In other words, he merely represented the zeitgeist of a certain age unlike say, Shakespeare. One can say pretty much the same about say, Bernard Shaw, Victor Hugo et al.

From this perspective, it’s a tribute to K Viswanath’s artistic vision that he not only captured the zeitgeist of the Indian society as it transformed before his own eyes but took the best of some of the lasting values in the Indian tradition that continue to define and inform our society.

Neither did he shy away from or hush up the unsavoury aspects of the same society. His movies proceed from the vantage point of accepting that these unsavoury elements like jati differences are real in the operating world. But he also shows the equally valid reality that these differences are merely organs of any community life anywhere in the world. The underlying subtext is also the fact that one can transcend these differences—which lie only at the level of the transactional world—because they aren’t absolute.

A good illustration of this is in the oblique manner in which an illiterate, “lower caste” washerwoman in Swati Muthyam tells the orthodox Radhika to consummate her remarriage, reassuring her by invoking the sanctity of Sita’s Mangalasutra around her neck, saying, “God has himself corrected the mistake he inflicted upon you.” This speaks volumes about K Viswanath’s approach to art, society, and life itself.

https://youtu.be/L4iQ-zrofUI?t=365)

Scene where Radhika is Reassured by a Washerwoman

This approach is the polar opposite of destructive ideologies and worldviews like Communism and Leftism which only, and always defines things in terms of opposition. Exploiter versus exploited. Upper caste/class versus lower caste/class. As is the wont with such a polar mindset, it doesn’t care to elucidate what will occur when the roles are reversed: which is what we’re witnessing across the globe today.

And so, when Viswanath’s movies depict all sorts of exploiters, charlatans, brokers and pimps in the world of dance and music, he also shows how this status may change at any time, and that it’s ill-informed to claim that these negatives are the defining features of any caste, community, profession etc. One can cite Shruti Layalu, and flashes in Sagara Sangamam as effective cinematic expressions of this phenomenon.

That Viswanath accomplishes this with matchless subtlety, nuance, and serenity is a greater skill and achievement. There’s no scope for loudness, sloganeering, and advancement of any agenda. Be it his depictions of caste and social anomalies in say, Sankarabharanam and Saptapadi, or his commentary on declining classical art forms in Sankarabharanam and Swarna Kamalam, there’s little by way of Vachyata.

The scenes in Swarna Kamalam where Venkatesh upholds the value of our traditional learning like say the Ghanapatam, or Bhanupriya’s belief that it is more rewarding to become a waitress at a five-star hotel than the heir to a great tradition of Kuchipudi are good testimonies to the aforementioned approach of Viswanath.

One can cite the classic scene in Sankarabharanam where the protagonist speaks about the value of Indian classical music and music itself as a universal value.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6pOd1O_8fIc)

J V Somayajulu Speaking about the Universality of Music

Or the reaction of Bhanupriya in Swarna Kamalam ) after she dances to her heart’s content and experiences artistic ecstasy, exclaiming that “I felt that all these art forms are useless for this world but now I feel that when they’re done with total involvement and dedication, I’ve experienced the real joy therein.” This harks back to Bharata Muni’s dictum of “yatho bhavostato rasah.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToNhJo7DqmE

Bhanupriya Confessing her Joy in Classical Dance

Which is how Viswanath provides the contour of solving such problems: through internal realization. In Sagara Sangamam, this takes the form of the haughty Shailaja who suspects her own mother’s fidelity and eventually realizes her mistake. In Swarna Kamalam, it’s in the scene of the Guru Puja where hundreds of her father’s students worship him even after he’s dead.

The powerful message is conveyed subtly: the progeny of Vidya is far greater than biological progeny, that it’s a value in itself.

--- V ---

If Viswanath’s movies depict various societal dimensions primarily using artistic themes as the central plot, these depictions are both infused with and inseparable from excellent portrayals of rural and the so-called folk art forms.

Villagers singing say, the Tummeda songs of which the Aura Ammaka chella number in Apadbandhavudu is a great example. As is the scene showing the vibrant tradition of composing Ashukavita (poetry composition on the spot) in the same film.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=--ydcCOelRg

Composing an Ashukavita in Apadbandhavudu

Or K Viswanath's excellent use of the Hari Katha tradition mentioned earlier.

Indeed, K Viswanath has used the Haridasa—Gangireddu Melam tradition in Andhra as a motif and a backdrop in his Sutradharulu. In a few crisp and nuanced scenes, he captures not only the art form and the community that has kept the tradition alive, but shows the unique importance of such micro-communities and the value they bring to the larger culture and society.

In a particularly poignant scene lasting less than a minute, the protagonist, an illiterate practitioner of Gangireddu, Akkineni Nageshwara Rao teaches priceless lessons about evil, the value of honouring tradition, and a nuanced response towards charity done by the wicked who are also enormously wealthy:

I took these gifts of clothes and money as a mark of respect for my tradition and not because the [wicked] Neelakantha gave them. A doctor gives medicine to even an evil person but doesn’t give poison and kill him. That is called the Dharma of profession. Take these clothes and money and throw them in Godavari.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDeR7QaJkjY

Akkineni Nageshwara Rao teaching the Dharma of Profession

Indeed, the sequences showing how the Harikatha art form is taught, and how it blends with the classical is creatively infused as part of the narrative. Indeed, the sequence where another protagonist, Murali Mohan enacts a scene where the Ox steps on his chest shows K Viswanath’s prowess in using mythological episodes effectively even as part of the Gangireddu Melam.

What’s also heartwarming is the cinematic rendering of the relationship between humans and cattle in a highly intimate fashion. This reminds us of a more elaborate and more intimate description that Dr. S L Bhyrappa gives in his classic novel Tabbaliyu Neenaade Magane of the revered place of and the deep, centuries-old bonding that Indians have retained for the cow and cattle.

One can also mention the creative use of rural folk donning Pauranika (mythological) roles and performing plays in rural Telugu dialect, the equally creative use of the compositions of Thyagaraja, Annamacharya, Bhadrachala Ramadasu, and so on. Apart from Marugelara (mentioned above) used in a romantic setting, one can also mention the lilting Inni Rasula set to the Malayamarutham Raga composed by Annamacharya.

In all of this, Viswanath completely sticks to native and classical elements be it in lyric and music and totally avoids Bollywoodian and Western elements. The fact that they’re still widely popular and hailed as classics and models to be aspired for is the testimony to their success.

And Viswanath accomplishes this feat by making them seem natural to the plot and not as an independent chunk included for its own sake, like generous blocks of unrelated “comedy tracks” so typical in commercial Telugu cinema.

The same can be said about the scenes showing for example, simple beliefs of villagers who tie cradles to trees as part of vows taken in the hope of begetting children. There’s an innate beauty to such beliefs rooted not just in tradition but in a fundamental understanding of human nature. This is the same understanding that makes Kamal Hassan tell Radhika in Swati Muthyam to wash the steps of the temple as a means to lessen and overcome her life’s sorrows.

The physical ambience for such brilliant artistic conceptions also plays a significant role in setting the context, unfolding the story, and enriching drama. The visual sweeps of the riverine Godavari landscape, age-old boats, cattle, children, temples, familiar village homes, Sanyasins, musicians, folk artists…every single ingredient blends and contributes to making the meal wholesome, delicious, and satisfying. Geography contributes to society to human life to art.

To be Continued