Richness of Emotion

V Si. said these words appreciating Sarma’s style of singing – “There may be many who can exhibit their learning in a seminar on musicology or keep the audience in awe of their singing ability while elaborating a rāga or playing with the tāḻa in a music concert. But I have not been able to find a single person like Sarma who can read the pulse of a kṛti and convey its emotions by appropriately using rāga and tāḻa. That singing is the effect of a connoisseur-artiste who understands the emotions and soul of the lyrical composition. He has a masculine voice. The characteristic of such singing is that the culturing of an entire life would flow in the form of music.”

Both in singing and in playing the violin Sarma had put in great practice and had attained mastery. During his youth, when he had visited Gerusoppè (Jog Falls) with his friends, he aligned his singing pitch to the high-pitched roar of the waterfalls and sang in that vocal range for quite a while – people who heard him have attested this.

Is Rāga Asāverī a bhāṣāṅga-rāga or not? In Rāga Begaḍè, is it the kākali-niṣāda note that must appear? Establishing such technical details by banging one’s fist on the table is a task that might interest but a few; it might also be much needed. But the need of the hour is to minimize the gap between the singer and the connoisseur, between literature and music.

From a holistic comparison of the Hindustani and Carnatic traditions of classical music, Sarma has said, “The purity of the notes in Hindustani and perfection in movement of svaras in Carnatic have gained prominence and have thus made these styles unique and distinct. But over-emphasis of these characteristics to the exclusion of others will sound a death knell to both these styles. Just as singing an apasvara is a sin in Carnatic music, changing of rhythm is a sin in Hindustani. We [i.e. Carnatic musicians] end up killing the audience by our Pallavi svaras and they give the audience a headache by elaborating the tāns.”[1] In this context, it would be worth-while to remember what Rabindranath Tagore said – “Music starts when prosody and grammar end.”

Sarma persistently argued at every possible opportunity that emotion is the soul of music. Music cannot flourish if either the pada (word) or nāda (melody) suffers.

A musical note becomes meaningful due to the words of a song. Therefore Sarma advocated the necessity of the knowledge of literature to musicians. Sarma stressed that it is imperative for singers to know the appropriate qualitative usage of notes and words when they sing different genres of music such as light music, classical music, and devotional music.

The theory that Sarma advocated through tens of his speeches and writings was – Music is an experiential art; it is an emotional outflow rather than a clash of svaras that makes a person experience tranquillity. During our times, it is rare to find anyone who can speak on both literature and music with the kind of authority that Sarma had.

Evergreen

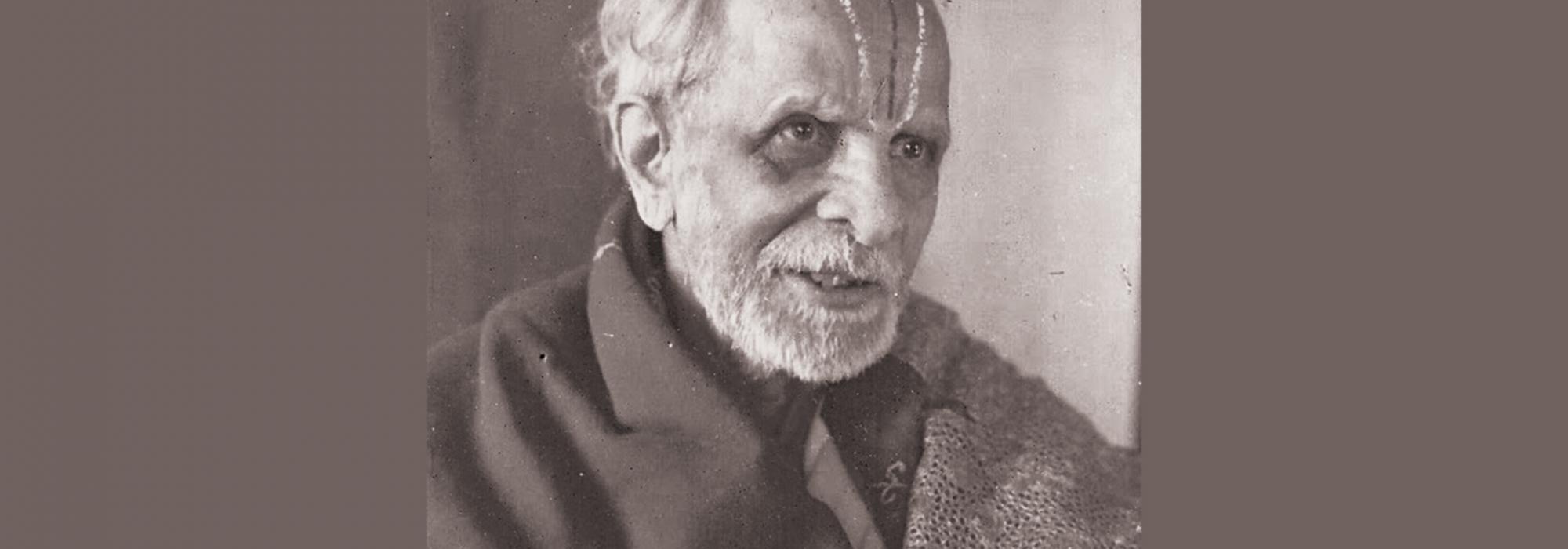

Madhunapantula Satyanarayana Shastri [a great classical poet of Āndhra] had described the analytical capability of Rāḻḻapalli Ananthakrishna Sarma as ‘Cirantana-vasanta.’[2]

Any curiosity-driven topic would not fail to bring out Sarma’s intellectual prowess. For example, in his essay ‘Nāṭakopanyāsamulu’ (‘Talks on Theatre’) he says, “Experiencing oneness in mundane worldly existence is called śānti (peace).”

While analysing the theme ‘Should women alone enact female characters?’ Sarma said, “There is nothing special about it. A tragedy should elicit a tragic feeling. Would it matter if it is a male or a female character who is crying?” His progressive view and thinking became evident when he unequivocally dismissed the contention that every drama or play should be agenda-driven to profess a moral.

In Nāṭakopanyāsamulu, Sarma has done a detailed analysis of several subjects such as drama being the culmination of several arts, the appropriate usage of lyrical creations in drama, female characters in drama, and so forth. We can recollect a few sentences as an illustration of his hearty writings. This relates to the mind of a connoisseur and is an attack on the ‘literalist’ mentality that repels enjoyment – “It is difficult to entertain those who idealize a certain school of thought and think that Naḻa’s wife should cry the same way my wife does, without there being an ounce of difference in the tears shed. Such people interpret things too literally and their value judgment of emotions is largely binary – ‘this is natural’ or ‘this is unnatural’ based on their limited experiences.”

Clarity and sharpness in thinking were amongst Sarma’s qualities. A singing competition based on film songs had been organized once and Sarma was one of the judges. When a participant informed the judges that he would be singing a song from the movie Meerabai, Sarma clarified, “In my opinion, it would be a devotional song and not a film song. However, if the audience agrees, I will have no objection. Simply because a Tyāgarāja kṛti or a Potana verse finds a place in a certain film, it will not render that a film song.” The participant sang another song, got appreciation from Sarma, and a prize too!

Learning

Rāḻḻapalli Ananthakrishna Sarma’s father Karnamaḍakala Kṛṣṇam-ācārya was not just a scholar; he had profound knowledge of poetry that was built on the edifice of adhyātma [loosely, ‘spirituality’] and praśānti [‘tranquillity’]. Naturally Sarma also imbibed these qualities.

He inherited his love for music from his mother Alamelumaṅgamma. There was no dearth of talent in Sarma but in addition to his talent, he underwent rigorous practice. For over a decade he learnt the Raghuvaṃśa, Campū-rāmāyaṇa, Campū-bhārata, Āndhra-rāmāyaṇa, Viśvaguṇādarśa-campū, etc. from his father Kṛṣṇamācārya through the traditional mode of learning. Since 1906, he was a disciple and follower of Śrī Kṛṣṇabrahmatantra Parakāla-maṭha Yatīśvara of Mysore. Further, he learnt several works such as Uttara-rāma-carita, Śākuntala, Mudrā-rākṣasa, etc. in the traditional manner from the famous scholar Rāma-śāstrī of Chamarajanagar.

Sarma was given the opportunity to assist the Parakāla-maṭha Swamiji in the writing of his work Alaṅkāra-maṇihāra[3], which is famous to this day. This process helped Sarma hone his literary skills. (The Parakāla-maṭha Swamiji had become old and his eyesight had become extremely weak.)

To be continued...

This English adaptation has been prepared from the following sources –

1. Ramaswamy, S R. Dīvaṭigègaḻu. Bangalore: Sahitya Sindhu Prakashana, 2012. pp. 122–55 (‘Rāḻḻapalli Anantakṛṣṇaśarmā’)

2. S R Ramaswamy’s Kannada lecture titled ‘Kannaḍa Tèlugu Bhāṣā Bèḻavaṇigègè Di. Rāḻḻapalli Anantakṛṣṇaśarmaru Sallisida Sevè’ on 11th July 2010 (Pāṇyam Rāmaśeṣaśāstrī 75 Endowment Lecture) at the Maisūru Mulakanāḍu Sabhā, Mysore.

Thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh for his review and for his help in the translation of all the verses that appear in this series.

Edited by Hari Ravikumar.

Footnotes

[1] Sarma hints at the weaknesses of the average performer of these systems of Indian music. The Carnatic musician is strong in tāḻa but slack when it comes to śruti. The Hindustani musician is strong in śruti but is slack with tāḻa. Also, both groups of musicians tend to overdo those aspects of music that they are technically strong in.

[2] ‘Evergreen.’ Literally, ‘forever the season of spring.’

[3] A treatise on poetics mainly connected with figures of speech.