Bharata, the mothers, and the army reached the vicinity of the Citrakūṭa mountain. Bharata observed, “The trees on the mountains scatter their flowers on the mountain slopes just as the dark water-laden clouds send down showers when the heat of the summer is over. Look at the startled deer, Śatrughna! As they quickly dart off, scared of our huge army, they look like banks of clouds in the sky flying before the wind in the autumn. These trees wear bunches of flowers on their heads supported by cloud-blue boughs just as the dākṣiṇātyas wear a garland of flowers on their heads. This forest, which was dreadful a moment ago and now filled with throngs of people looks like Ayodhyā to me. The dust raised by the horses’ hooves darkens the sky, but the wind dispels it quickly, as if it wished to please me. Those lovely peacocks are frightened and are retreating quickly to the mountain. Let the army look for Rāma and Lakṣmaṇa here.” His men soon told him that they had spotted smoke at a distance. Hoping that it indicated the presence of his brothers, Bharata went ahead with Sumantra and Guru Vasiṣṭha.

Around the same time, Rāma was telling Sītā, “Nothing bothers me as I see this lovely mountain. I can live here all my life with Lakṣmaṇa and you, my dear wife, without feeling any pain. I have gained two fruits due to my stay in the forest – I have cleared my father’s dhārmic debt and Bharata has been pleased as well. Vaidehī! I trust you too are happy being with me on Citrakūṭa. My ancestors who were rājarṣis regarded this discipline of the forest life as amṛta and gateway to well-being after death. At night, the herbs on this lordly mountain look like the tongues of fire as revealed by their own luminescence. The Citrakūṭa appears as if it has risen splitting the earth.” Rāma also pointed at the crystal-clear waters of the river Mandākinī, its sandy shores, and the ṛṣis who perform tapas there. He suggested, “Consider the wild animals in the forest as the citizens of Ayodhyā, the mountain as the city, and the river Mandākinī as Sarayū. I do not crave for Ayodhyā or the kingdom. Bathing in this delightful river adorned by fully blossomed trees, one can shed fatigue and feel elated.”

As he walked along the lower altitudes of the Citrakūṭa speaking thus to Sītā, Rāma noticed the dust and noise of Bharata’s army rising to the sky. As Rāma instructed him to look for the cause of the tumult, Lakṣmaṇa climbed a tall sal tree and spotted a vast army to the east. He rushed to his brother and asked him to put out the fire and leave Sītā in the safety of a cave. He asked Rāma to get ready with his arrows, armours, and bow. When Rāma asked him whose army it was, Lakṣmaṇa replied in wrath, as though he would burn the army with his eyes, “Now that Bharata, Kaikeyī’s son, has been coronated, he is coming to kill the two of us. I can see the insignia of the kovidāra tree atop his chariot. Your enemy has arrived, Rāghava, the cause of your expulsion from the kingdom. It is Bharata and I will kill him – I see no wrong in doing so. Once he is dead, you will rule the vast earth. Today, Kaikeyī, who desired the kingdom, will be harrowed by grief seeing her son slain by me. I shall slay Kaikeyī too, her supporters and kinsmen. Let the earth be cleansed today of this foul scum! I will drench the woodlands of Citrakūṭa with my enemies’ blood!”

In order to calm Lakṣmaṇa, who was violently agitated with insensible rage, Rāma said, “It is indeed appropriate for Bharata, an excellent archer and a man of immense wisdom, to come and see us. He would never even think of causing us any harm. When has Bharata ever caused you any trouble that you should harbour such suspicions about him? You should not utter an unkind word about Bharata. If you do so, it is as good as hurling criticism at me. Would a son ever kill his father, or a brother his own brother, who is the very breath of his life? If you are speaking so because you desire the kingdom, I will instruct Bharata to handover the kingship to you. He will agree without a moment’s delay.” Looking at Lakṣmaṇa’s distressed being, Rāma said, “I think Bharata has come here only to visit us, or perhaps, to take Vaidehī back home. You can see the splendid horses and the army led by the aged, mighty elephant Śatruñjaya, belonging to our father.” Now consoled, Lakṣmaṇa climbed down the sal tree, and waited by the side of Rāma with folded hands.

Camping his army at a distance, Bharata went ahead looking for Rāma and instructed Śatrughna, “I shall find no peace until I see Rāma and bow my head at his feet; I shall find no peace until I see the powerful Lakṣmaṇa and the illustrious Vaidehī. I shall have no peace until Rāma is seated on the throne of our kingdom. How blessed is this Citrakūṭa Mountain to host Rāma!” As he searched, he spotted Rāma’s āśrama and hurried towards it along with Guha.

As he neared the thatched hut of Rāma, Bharata noticed split logs of firewood and heaps of flowers that had been gathered. In the forest nearby, he saw heaps of dry dung of deer and buffalo collected for burning to ward off cold. As they proceeded, Bharata excitedly remarked to Śatrughna, “This must be the spot that Sage Bharadvāja spoke of. Clothes made of tree-barks are tied up high on the trees; Lakṣmaṇa must have fastened them in this manner to mark his trail as he heads out at odd hours. You can see thick smoke at a distance; it is customary for ascetics to maintain fire continuously in forests.” He addressed the people with him, “O! Cursed be the day I was born and cursed my life. It is on my account that this calamity has befallen on Rāghava and I am condemned by all the world. I will beg for forgiveness from Rāma and Sītā. I will fall at their feet again and again.”

Even as he thus lamented, Bharata saw a large and enchanting hut, that was thatched with the leaves of sāla, tāla, and aśvakarṇa. Kuśa grass was spread around the hut and it appeared like a yajña-vedī. Bows that looked like rainbows and arrows that flashed like sunbeams adorned it; Bharata also saw swords, shields, forearm-guards, and finger-guards studded with gold hanging there. He also saw a vedī with blazing fire in the north eastern direction of the house.

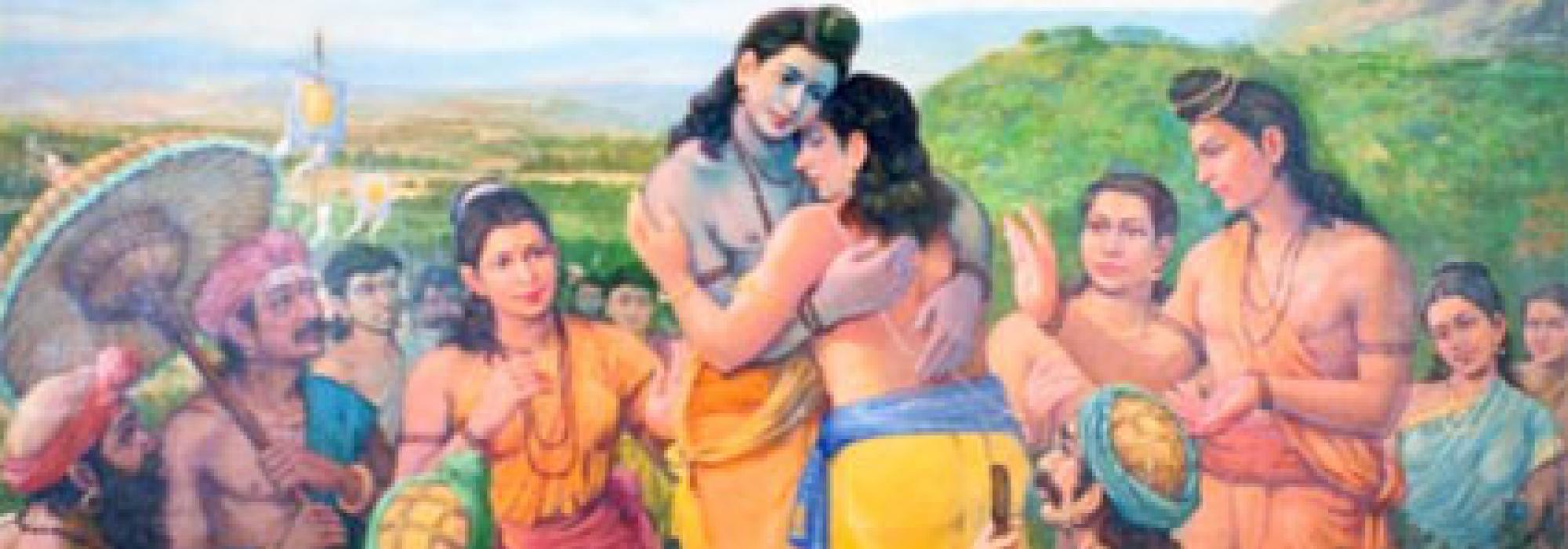

As he glanced around for a moment, Bharata spotted his revered Rāma clad in tree bark and deer skin, wearing matted hair and blazing like fire. He saw Sītā and Lakṣmaṇa seated next to him. Bharata was overwhelmed by sorrow and he said with his voice choking, “The person to whom his subjects in the assembly should pay homage is being attended upon by wild beasts. It is my fault that this misery has befallen Rāma! A vile creature that I am, an object of scorn to the entire world!” He collapsed weeping before he could reach Rāma’s feet. He only called out, “Ārya!” Śatrughna fell at Rāma’s feet as well and Rāma hugged them both.

Rāma took Bharata on to his lap and asked him[1], “What has happened to your father, my child, that you have come to the forest? As long as he is alive, your place is not in the forest. I am seeing you after such a long time, Bharata! You have changed beyond recognition! I trust that King Daśaratha is in good health, performing aśvamedha and rājasūya-yāgas. I hope that the upādhyāya of Ikṣvākus is being honoured adequately. Are Kausalyā and Sumitrā well? Hope the noble queen Kaikeyī is happy. I trust you still honour your purohita and I hope have appointed a knowledgeable person to take care of Agni. I trust you continue to hold the upādhyāya Sudhanva in high esteem, dear brother. I hope you have appointed as ministers reliable men, who are resolute, well-versed in polity, self-controlled, and belong to good families. They must be able to understand your intentions in no time. Good counsel is the basis of a king’s success, Rāghava! I trust you are not ruled by sleep, but wake up early and reflect on the principles of prudent statecraft late at night. I hope you do not make decisions all alone or consult too many people. A brave and wise minister is better than a thousand fools. I trust that people have no reason to despise you. I hope you honour your foremost soldiers and pay the appropriate wages and rations to your army. If the schedule of payment is missed, servants grow angry and get easily corrupted. I hope you choose a discerning man as your envoy, who is faithful, born in your kingdom, and repeats exactly what is told to him. I hope your spies who are undercover know the hearts of the eighteen chief officials in the foreign state and fifteen for your own; three spies need to be appointed for every official. I trust you do not associate with brāhmaṇas who are materialists.

I hope the city gates of Ayodhyā, true to the city’s name, are unassailable. I hope people belonging to all the four varṇas live in comfort and harmony. I trust the devasthānas are flourishing and agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade are going well. A well-founded economy promotes happiness in the world. I hope your revenue exceeds your expenses and your treasure does not pass into unworthy hands. I hope no honest person is charged with theft and thieves are not set free out of desire for wealth. You pay homage to the aged, to ascetics, guests, deities, caityas, and brāhmaṇas, don’t you? I trust you are not causing harm to artha in the name of dharma and to dharma in the name of artha; and I hope that dharma and artha are not being sacrificed for the sake of kāma. I hope you have organised your time to devote adequately to each of dharma, artha, and kāma.

I hope you are free of the fourteen flaws common to a king – nāstikya, dishonesty, anger, heedlessness, procrastination, shunning the wise, indolence, sensuality, autocracy, consulting men who mislead, failure to act upon decisions, failure to guard one’s counsel, skipping auspicious rites, and attacking many enemies at once. Finally, I trust you never savour foods alone and you offer aid to allies when they seek it.”

Bharata, upon listening to Rāma’s words, replied, “The eternal dharma says that when the elder brother is alive, the younger should not become the king. So, you must come back with me, Rāghava. When I was away in the country of the Kekayas, our king passed on to svarga. Arise, my dear brother, offer waters (tarpaṇa) to our father. Śatrughna and I have already done so.

Hearing the words of Bharata, which struck him like a bolt of lightning, Rāma lost consciousness and collapsed. His brothers and Sītā wept as they sprinkled water upon him and helped him regain consciousness. He lamented, “I am a wretched son. My father died of grief for me, and I could not even perform his final rites. Ayodhyā has lost its lord and its direction. I can never bear to go back to the city. Sītā, you have lost your father-in-law, and Lakṣmaṇa, your father!” Rāma offered waters to his dead father on the banks of the river Mandākinī. With his brothers, he offered food to his departed father, in the form of the iṅgudī cake mixed with badarī fruit. Out of deep sorrow, he said, “Eat with pleasure, great King, such is the food as we ourselves now eat!”

Rāma returned with his brothers and Sītā to his hermitage and started weeping. Their cries echoed around the mountains and Bharata’s soldiers hurried to the spot.

To be continued...

[The critically constituted text and the critical edition published by the Oriental Institute, Vadodara is the primary source. In addition, the Kannada rendering of the epic by Mahāmahopādhyāya Sri. N. Ranganatha Sharma and the English translation by Sri. N. Raghunathan have been referred.]

[1] The questions posed by Rāma which constitute the ninety-fourth sarga in the critically constituted text is called the kaccit-sarga. It captures the dhārmic duties of a king and Rāma’s concern for the kingdom.