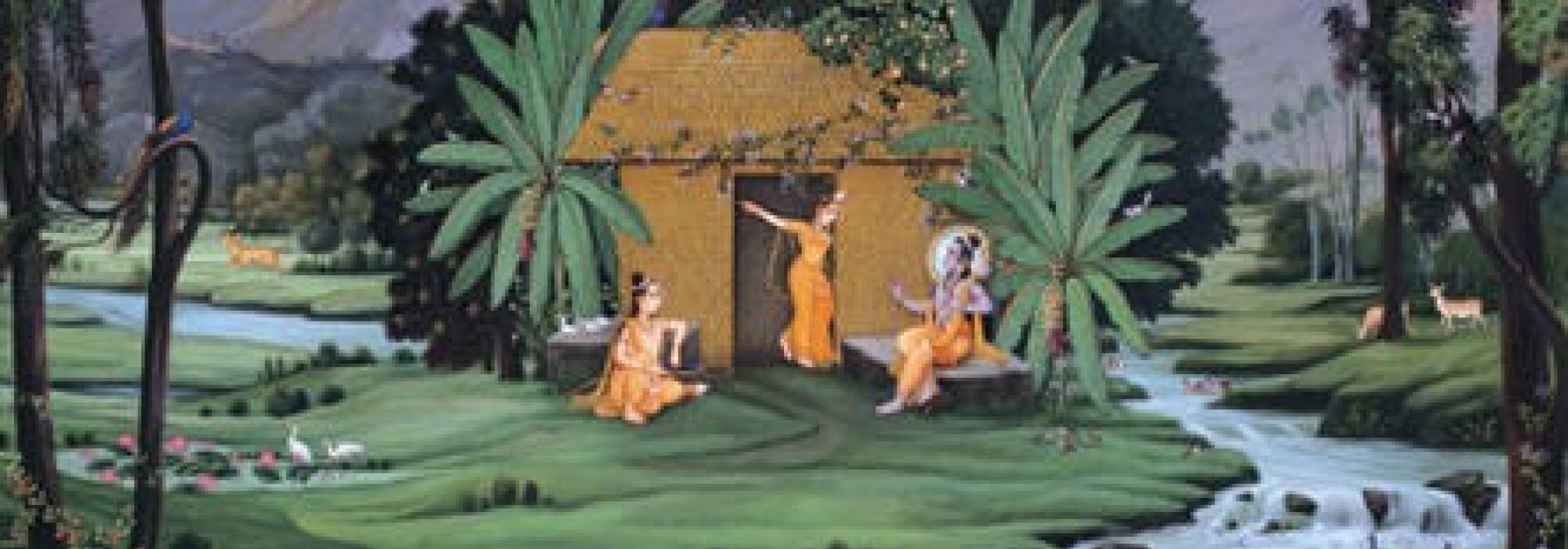

The next morning, Rāma awoke Lakṣmaṇa and they set out into the forest. Rāma enjoyed the beauty of nature and pointed it out to Sītā as well. Spellbound with the flora and fauna in and around the Citrakūṭa Mountain, Rāma decided that they should reside there. Upon Rāma’s instruction, Lakṣmaṇa built a parṇa-śālā – leaf-hut and then killed a black antelope to perform bali as a part of the housewarming ritual. Enjoying the beauty of the mountain and the pleasant river Mālyavatī, Rāma overcame the sorrow of having left his beloved city.

~

After Rāma left them behind, Sumantra spoke for a long time to Guha and returned to his city. As he entered Ayodhyā that was consumed by grief, people rushed to him hoping that he would have come back with Rāma and were deeply disappointed. Daśaratha and Kausalyā were heartbroken seeing Sumantra who had returned empty-handed. Upon the king’s behest, Sumantra conveyed to him Rāma’s greetings and message. He also recollected Rāma’s request to Bharata, “Treat all mothers with the same kind of love and respect. Once you are elevated to the position of prince-regent, you must defer to Father, who remains the king.” Sumantra continued, “But Lakṣmaṇa looked furious as we were parting ways. He wanted to know for what offence Rāma had been exiled. He also said, ‘I no longer consider the King as my father. Hereafter, Rāma is brother, father, master, and every kinsman to me.” Regarding Sītā and Rāma, Sumantra said, “The noble Jānakī, who had known no grief or hardship, stood motionless heaving sighs and said no word to me. She gazed up at her lord, her face parched by grief, and burst into tears as she followed me with her eyes when I departed. Rāma stood still, his hands cupped in reverence and supported by Lakṣmaṇa’s arms.”

Sumantra continued, “Even after they left, I waited for many days there with Guha, hoping that Rāma might call me again or send a word for me. As I heard nothing from him, I returned to this joyless city, where the nature is grieving with its people.”

Upon hearing these words, Daśaratha lamented and fell back on his bed in a faint. Kausalyā lamented and Sumantra tried to comfort her with his own voice choking. He said, “Rāghava is living in the forest without any regrets. Sītā, like a young girl is enjoying herself, delighting in Rāma, for her heart belongs to him and her life depends on him. As they walk, Sītā joyfully asks about every village, river, and tree she sees. Even now, when she has cast off her jewellery out of love for him, Vaidehī moves playfully as though she were dancing with jingling anklets. Whenever she sees an elephant, lion, or a tiger, she slips into Rāma’s arm and feels protected. The three have resolved to follow the path of the maharṣis. Don’t worry.” Still, Kausalyā couldn’t stop herself from moaning. She cursed the king and said, “Even when Rāma returns in the fifteenth year, he will spurn the kingdom and kingship which has been enjoyed by Bharata. A noble elder brother will not accept a kingdom that has been savoured by the younger one. A tiger will never eat the meat that another beast has feasted upon. And also, listen! A woman’s first refuge is her husband, second her son, and third her kinsmen. Of these, you are lost to me, and Rāma has gone to the forest – you have destroyed me and my son. Your son and your wife will now rejoice.” On hearing these harrowing words, the king plumped into an abyss of grief and recollected his evil deed of the past. He begged for forgiveness and sought Kausalyā’s affection.

On the sixth night after Rāma’s exile, Daśaratha narrated to Kausalyā –

“Dear one, a person receives the fruit of his good and bad deeds in the same measure. I was a brilliant bowman in my younger days when I was the prince regent and was not married yet. I had mastered śabda-vedhi – I could shoot at the target just upon hearing its sound. Just as a little child might eat something poisonous out of ignorance, I was unaware of the consequences of the art of shooting by the ear. It was the rainy season that breeds lust and pride in men. I decided to get some practice and I set out hunting at night along the banks of the river Sarayū. In the thick darkness, I heard a noise which sounded like an elephant, but was actually a pot being filled with water. I shot an arrow into the air and heard a human voice scream in pain, “Ah! Ah!” It was the voice of a young seer. As he fell into the river, he called out “Who would kill a tapasvī like me? I only came to fetch water in the river. I do not grieve for my own death as I do for the plight of my father and mother when I am gone. They are both blind and frail. They will now have to endure their thirst, as long as they can, on the strength of hope alone.” He pleaded me to pull out the arrow from his body and as I did so, he started heaving painful sighs as he lay on the bank of the river.

As I headed to his parents’ āśrama, upon hearing my footsteps, mistaking me to be his son, his father asked me – “Why did you take so long, my child? You are our eyes and very life.” I then confessed my mistake and told the old couple about the passing away of their son. Listening to this, the aghast father, told me with folded hands, “O king! If you had not yourself told me of this evil deed, your head would have been instantly shattered. If a kṣatriya wantonly kills a vānaprastha, he will topple down from his exalted place. You are alive because you did this out of ignorance.” Upon their request, I took them to the place where their son lay dead. The old couple bewailed uncontrollably. But then, the son appeared in a divine form and consoled them saying that he had attained a great place in svarga as he had served them well. The father then cursed me, “You shall die from grief for a lost son, just as I do!”

“Kausalyā, the words of the noble sage have come true. I am not able to see you. The messengers of Yama are here, hastening me on. Those who are privileged to see Rāma back in the fifteenth year are truly devas, not mere humans! Ah Rāghava!”

With these words, the king drew his last breath.

~

The next morning, bards and women who went to awaken him, were suddenly apprehensive upon seeing him. They wondered if the king was actually alive. The women cried out loud upon discovering the truth. Their wails awoke Kausalyā and Sumitrā who had collapsed nearby. The two queens were absolutely crestfallen.

Kausalyā cried out to Kaikeyī, “You can now have your way, vile woman, and enjoy the kingdom free from all troubles. Only an adhārmic lady like you will continue to live upon the death of her husband. When Janaka gets to know that the king, acting under illicit compulsion, has exiled Rāma, he will lament as I do. He too will lose his life thinking of the torments his daughter will face in the forest.” As she lamented, her maid-servants embraced her and led her way.

The ministers placed the king’s body in a tub of oil and took charge of all the royal duties they were empowered to execute. They preserved the body as they did not want to perform the final rites in the absence of a son. Lack-lusture like the day-sky without the Sun, the city was filled with people whose voices were choked with tears. Men and women gathered in groups and condemned Bharata’s mother.

~

The next morning, several brāhmaṇas including Mārkaṇdeya, Maudgalya, Vāmadeva, Kāśyapa, Kātyāyana, Gautama, and Jābāli spoke to Vasiṣṭha, the royal purohita. The expressed their concern about the kingdom that was now bereft of king. They said, “King Daśaratha is gone and all his sons are away. In a land without a king, the clouds will not rain and no seeds are sown; the son does not obey his father or the wife, her husband; brāhmaṇas won’t perform satras and no festivals are celebrated. In a kingless realm, storytellers find no audience and merchants are not safe. In a country devoid of a king, munis who are ātmajñānīs cannot be found; the yoga and kṣema of the kingdom are lost and the army cannot face an enemy in the battle. The realm that does not have a king is like a river devoid of water and cows without herdsmen. Like fish, men start devouring each other. The adhārmic nāstikas can be brought under control only by a king. O great brāhmaṇa, name some other prince of the Ikṣvāku clan and coronate him!”

Vasiṣṭha instructed royal messengers to hurry to Rājagṛha to fetch Bharata. He asked them to keep their sorrow in check and not reveal any incident that had taken place in Ayodhyā.

~

The very night the messengers entered the Rājagṛha, Bharata had an unpleasant dream. As his friends tried to ease his mind, Bharata recounted what he witnessed in the nightmare – “I saw my father in dirty clothes, falling from a mountain into a pool of cow dung. He was drinking sesame oil from his cupped hands and hysterically laughing all the while. The ocean had gone dry and the moon had fallen on the earth. The earth split open and the mountains crumbled. The king lay collapsed on a black iron throne and there were women mocking him. I saw him hurrying off towards the South on a chariot pulled by donkeys. The dream certainly signifies death in the family. I am terrified!”

The messengers reached the palace and escorted him to Ayodhyā.

~

As Bharata entered Ayodhyā he observed that the city was devoid of its former exuberance. The crossroads, streets, and houses were empty. Sick at heart, Bharata entered his father’s residence.

To be continued...

[The critically constituted text and the critical edition published by the Oriental Institute, Vadodara is the primary source. In addition, the Kannada rendering of the epic by Mahāmahopādhyāya Sri. N. Ranganatha Sharma and the English translation by Sri. N. Raghunathan have been referred.]