This is a summary of the speech that I delivered on Sunday, 29th April 1953 on the occasion of unveiling a portrait of Prof. Bellave Venkatanaranappa, one of the founding members of the Basavanagudi Union and Service Club.

Prof. Bellave Venkatanaranappa has become a recipient of our eternal gratitude and respect for many reasons. Those reasons can be divided into three broad categories: first, he was a founder of this club; second, he was an exemplary citizen; third, merely from the point of view as a human being, he is worthy of our reverence.

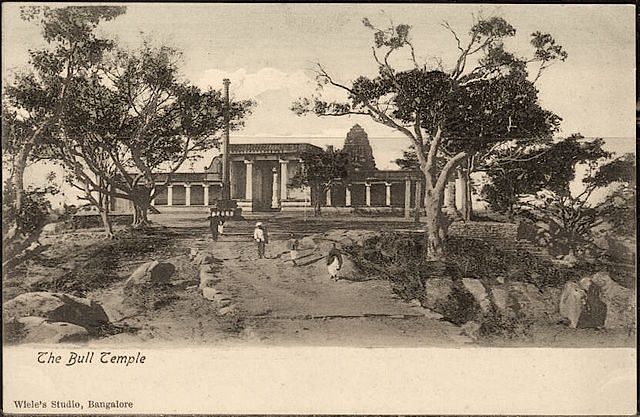

About fifty years ago, when the Basavanagudi locality was still in its early stages, Venkatanaranappa decided to build a house here. After a few houses sprung up here, he felt the need for a place where the householders from this locality could get together as friends and spend their time in a jolly manner. He got together with two of his friends and began thinking about this goshti mandira (literally ‘congregation temple’). After the plot had been acquired, Venkatanaranappa took the lead in constructing the buildings. At that point, the material facilities to execute that task were in short supply. Therefore, Venkatanaranappa himself undertook several activities that were physically arduous. When the bricks arrived in a cart, he would immediately have it lowered, then counted, and finally moved to the place where all the bricks were stored. He would himself mix mud and cement and build the walls. Of all the walls of this good-looking mandira, a portion was built by Venkatanaranappa with his own hands.

Much more than constructing these buildings he toiled to manage the affairs of this goshti. Even in those days it was a pain to collect donations. With a membership book and a receipt book under his arms, Venkatanaranappa would roam from home to home and earned the title of ‘Nakshatrika’ [A disciple of the rishi Vishwamitra who was over-zealous and pestered Harishchandra to no end.] Club members and friends would – with or without the knowledge of the secretary – borrow newspapers, periodicals, and books that were obtained for the reading room of the goshti, and often fail to return them. And those who returned them would tear off the pictures, crumple the books, or soil them. Venkatanaranappa was not one to fear an attempt to put an end to such atrocities. The reward he received for that devoted service was mere acrimony.

He had great hopes in the matters of this club. I remember vividly the two or three times that he brought me here and tried to teach me how to play cards. He realized quite soon that I was incapable of succeeding in learning cards, just as with other areas.

Those who saw him from afar felt that he was a severe person, extremely puritanical, and had no place for jokes and humor. At least, that’s how he seemed. But those who came a little closer to him didn’t take long to encounter his sense of humor and fun. I have not seen too many connoisseurs apart from him who could laugh aloud like a child at a clean joke or provide solace and support to those in pain and bitterness.

Now let us recall his role as a responsible citizen. When a new suburb is established, what are the necessities for the convenience of people who will live there? It was only after ascertaining these details that Venkatanaranappa would begin his work. That is how the Sri Mallikarjuna Temple was established. Even there, Venkatanaranappa himself built the walls. Every year, during Shivaratri [during February-March] he would apply a coat of slaked lime, thus making the temple appear new. He would get the accounts of the temple written without a discrepancy of a single paisa; then he would bring together an assembly of eminent citizens and submit these accounts to them. He also worked in many citizen groups and civic bodies.

There was an attempt to build a market in Basavanagudi. He was the superintendent of the Ratepayers Association here. He played a major role in the functioning of several co-operative societies. He had taken the responsibility of several charitable organizations. You are all quite familiar with how he labored for the establishment and development of the Karnataka Sahitya Parishat, served as a member of several committees in the university, and was part of many other organizations where he worked with great devotion sans personal motives.

Venkatanaranappa was a person who worked for the welfare of people in numerous ways. His public spirit is worth emulating by all. That was a time when there was no other recompense for such tireless striving except for the bitterness of many people. Of course, I harbor no such illusions that in today’s time there would be a slew of awards for someone as selfless and outspoken. We find that the reward for ನಿಷ್ಠೆ (consistency, loyalty, devotion, excellence) is always ನಿಷ್ಠುರ (bitter, acrimonious, angry). Even so, the people who didn’t have the taint of selfishness or reason for jealousy maintained great respect for Venkatanaranappa as a man of integrity and uprightness.

If we just look at Venkatanaranappa as a man, merely from the point of view of humanity, he is worthy our worship. He had the same purity within and outside. What was in his mind was in his words; what he spoke, he acted upon. He was a courteous man who conformed to traditional practices. This would become evident merely upon seeing his person. But he was not a man of blind beliefs. He agreed that several changes were required in our traditional practices, and whatever changes he felt were appropriate, he applied to his own practice. As much as he seemed severe from outside, he was as gentle and affectionate from within. He had the heart of a child and was endowed with tender sentiment. I have seen him speak in a furious voice even as he was shedding tears. Bhavabhuti’s words ‘ವಜ್ರಾದಪಿ ಕಠೋರಾಣಿ ಮೃದೂನಿ ಕುಸುಮಾದಪಿ’ (Hard as a diamond, soft as a flower) is apt in his case.

About fifteen or twenty days before his death, I was sitting next to him, chatting. The room where he was lying down faced the street. The road dust as well as the sound of the vehicles and buses were beyond tolerable limits. I suggested that he move to a room in the Eastern end of the house, far removed from the street and lie down there instead. His response was typical of his behavior: “In the room behind this one, my granddaughter often plays the violin. I hear the constant chatter and laughter of children. There is no opportunity for this joy in the other room that you’re suggesting.”

Even I didn’t realize how much affection Venkatanaranappa had for music and for the chatter and laughter of children. His mind was like the fresh butter-ball in a strong earthen pot. The eyes of the world saw the firmness of the pot. Those who cared to lift the lid saw the butter.

Who wouldn’t want to recollect such a man? Today is a great day for me. I feel that all of you also share a similar feeling for this great day. I am extremely grateful to you for having given me a share in performing this noble act of making Venkatanaranappa’s memory perennial.

This is the seventh chapter from D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 1) – Sahiti Sajjana Sarvajanikaru. Translator's notes in square brackets. Thanks to Sandeep Balakrishna for his astute edits and Shashi Kiran for his timely help.