DVG’s conception of a strong and prosperous Bharata was a mixture of Yoga and Kshema; Yoga in the sense of having an opportunity to obtain something and Kshema in the sense of retaining and sustaining it safely.

Blend and Balance

These ideals operate at the level of the Samashti (the nation and society) and act as guideposts for organizing and governing a nation and society. No matter however noble and lofty these ideals may be, they’re mere “paper flowers” (to use DVG’s expression[1]) unless they are tested in the real world. Which is why, in consonance with the ancient Indian ethos, DVG also constantly emphasizes on the role, importance and duties of the Vyashti (the individual, the citizen). Not just that, he also shows the blend and balance that must exist between the mutually-dependent entities of Vyashti and Samashti. One can distill the chief characteristics of DVG’s eloquence on this subject in the form of the following phrases:

- Dharma

- Rashtraka Praja or Nationalist Citizen

- Rashtra Sharira or the National Body

- Rashtraka Tattva or the Philosophy of a Nationalist

- Rashtraka Prajna or the Nationalist Consciousness

- Atma Guna or Soul Quality

- Swabhava Parishodhana or Constant inquiry and purification of the nature of things (and of the individual)

In keeping with these, DVG was one of the pioneering advocates of what’s known as “clean politics” decades before the phrase became popular. But this cleanliness was not limited just to method and execution; he showed how it is possible to clothe politics and public life with Atma Guna.

Notions of Freedom

One of the most illuminative treatises that demonstrates this is DVG’s learned expositions on freedom. He unequivocally gives primacy to the role and responsibility of the individual in the practice of freedom. Accordingly, freedom is deserving of a people endowed with self-restraint, self-introspection, continuous refinement of character, and questioning whether an individual is deserving of something before demanding it. Decades later, the eminent Indian jurist Nani Palkhivala obliquely echoed[2] the same tenets when he stressed on “obedience to the unenforceable.”

In keeping with the ancient Indian spirit of all-inclusiveness, here is how DVG conceives[3] the notion of freedom.

Freedom as a principle is an indivisible whole. One cannot break it down into pieces [and still claim that one is free]…freedom is the opportunity for every individual to make decisions about any aspect of his life without restraints imposed by others by using his independent judgement and wisdom.

Contrary to the notion of unlimited and unfettered freedom that Ayn Rand-inspired libertarians espouse today, DVG is firmly wedded to the reality of intrinsic human impulses and has a keen understanding of the realities and lessons of history.

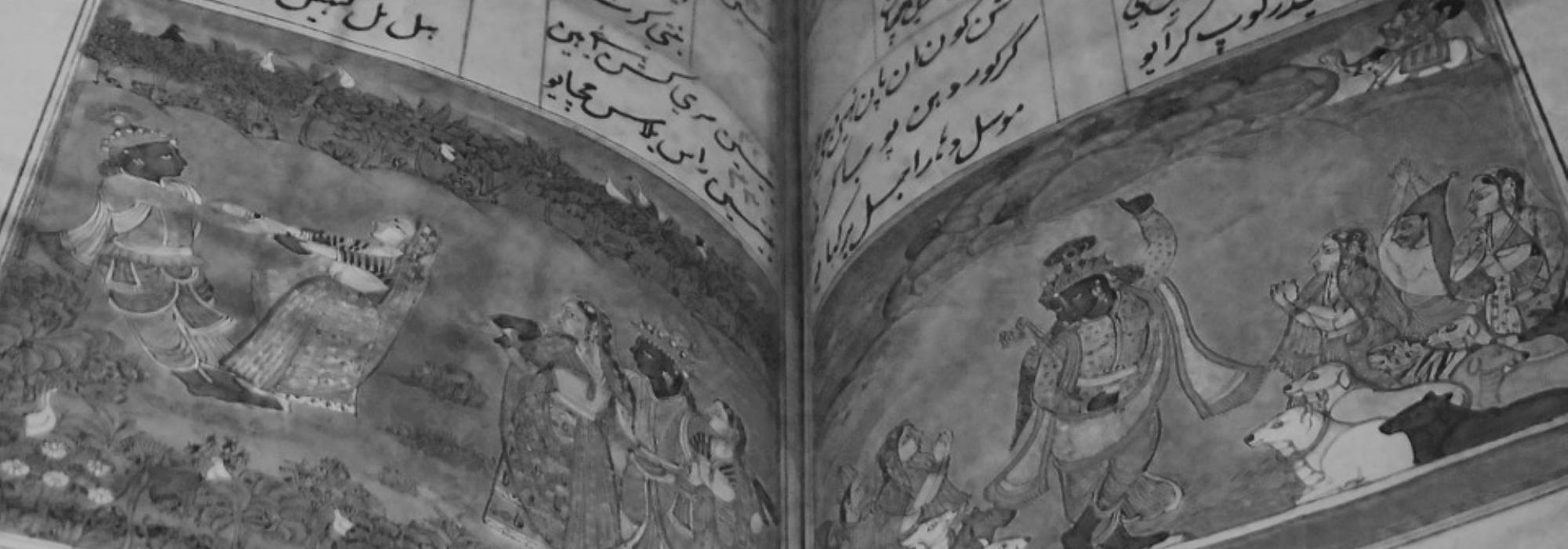

Accordingly, DVG assigns the proper place to the notion of freedom, which he says, is of recent origin. In the era[4] of kingdoms, “the notion of ‘ruler’ was greater than that of the ‘citizen.’” Just as wild animals were domesticated over centuries, just as conveniences like railways, bicycle, motor vehicles, and technology evolved over centuries, so did political systems evolve by trial and error and experimentation. Therefore, the political systems that were once largely the preserve of the warrior class evolved into a system of kings, ministers, councils and judges. In other words,[5] over time, “these systems became citizen-oriented. The notion of individual freedom therefore belongs to a political system that is citizen-oriented.”

Viewed from this historical perspective, the question that logically arises is this: individual freedom to do what? The idea of individual freedom that first arose in the West, after passing through various trajectories, can be summed up as follows:

- Freedom to dress, eat, drink, think, write, and speak even what is considered unpopular and sacrilegious because the moment freedom is subject to any restriction, it stops being freedom. This is also known as free speech absolutism.

- Non-censorship of any form: on books, public speeches, art, music, cinema, etc.

- Primacy of the rule of law. That is, all freedoms are guaranteed as long as they don’t violate the freedom of another individual or don’t militate against the law of the land.

All of these ideas have been implemented and are operating in varying degrees in the USA and most countries of Western Europe. However, whether the actual outcome and consequence of this has been positive and desirable is still a matter of debate. More than twenty years ago, modern Singapore’s founding father and its longest-serving Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew made[6] the following observation:

Good governance…requires…upholding fundamental truths: that there is right and wrong, good and evil…The ideas of individual supremacy and the right of free expression, when carried to excess, have not worked. They have made it difficult to keep America society cohesive. Asia can see it is not working.. In America itself, there is widespread crime and violence, old people feel forgotten, families are falling apart. And the media attacks the integrity and character of your leaders with impunity, drags down all those in authority and blames everyone but itself.

Arguably, this state of affairs is the direct consequence of not fully thinking about the goal sought to be achieved after individual freedom has been fully realized. Besides, the Western conception of individual freedom primarily arose as a reaction to centuries’ long oppression of the majority of their population by the Church apparatus and a political system controlled by a complex and interconnected web of a nexus between the Church, the State and robber barons.

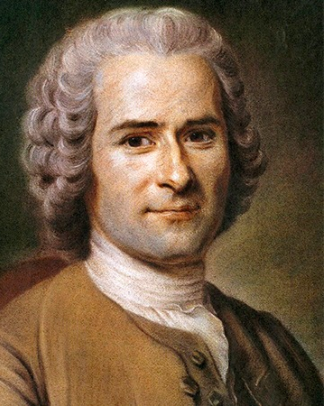

In this backdrop, DVG accurately analyzes the origins of individual freedom by providing a pithy critique[7] of Jean Jacques Rousseau.

The teacher of today’s world is Rousseau, the political philosopher who sowed the seeds of the French Revolution. He preached that freedom is the birthright of every person. Both Government and law are artificial constructs. A person must safeguard his natural rights within their confines…Although the underlying principles of his teaching aren’t erroneous by themselves, he placed a greater emphasis on rights. In their fight for rights, people paid less attention to duties. It is this neglect of duty that is the root cause for the worldwide turmoil today.

To provide yet another illustration of DVG’s foresight and prescience of fundamental analyses, one can cite the example of the thinker and author Paul Johnson writing[8] about Rousseau more than fifty years later. Unlike DVG’s restrained but firm language, Johnson is brutal, merciless, and accurate.

[Rousseau] moved the political process to the very center of human existence by making the legislator, who is also a pedagogue, into the new Messiah, capable of solving all human problems by creating New Men. ‘Everything,’ he wrote, ‘is at root dependent on politics.’ Virtue is the product of good government. ‘Vices belong less to man, than to man badly governed.’…Politics will do all. Rousseau thus prepared the blueprint for the principal delusions and follies of the twentieth century.

In spite of his constant emphasis on idealism, DVG was neither blind to harsh realities nor was he unsparing in his criticism of one-sided hortatory. At every step, he stressed on the “duty of pre-examination” before embarking[9] on “adopting the child of feelings” emanating from the West. Thus, as early as in 1952, DVG cautioned that the feelings of equality, liberty and fraternity that had already become widespread in India weren’t working properly in the geography of their origin. This critique will be taken up for a more detailed examination later in this volume. He diagnosed[10] that the

…chief defect in these conceptions is that they cut off the human touch from human interactions. The relationship between humans, instead of becoming one between hearts, is becoming a lifeless, mechanical task. No matter what prosperity accrues to the physical body by these new notions, they are proving proportionately detrimental to the richness of the soul.

The goal and objective of freedom according to DVG is the flowering and fulfilment of the soul at the individual level, and the sustenance and defense of Dharma at the level of the society and the state. No matter how noble the intent, the state must not place hurdles in the flowering of the citizen’s spirituality. This mutually-dependent and indivisible relationship is a serious responsibility as also a joy arising from purifying one’s Atma Shakti or inner strength.

At the individual level, the pursuit of freedom must follow this dictum of the Bhagavad Gita[11]:

uddharedAtmanAtmAnam ||

Let a person raise himself by his own efforts.

DVG’s exposition is also a reflection of the Bhagavad Gita’s emphasis on the supremacy of Svadharma (one’s own duty) and the true freedom[12] ensuing from the cultivation of one’s “Inner Government over that of the Outer Government.” Stronger the Inner Government, lesser one’s need for external regulation.

To be continued

Footnotes

[1] D V Gundappa: Rajyashastra, Rajyanga—DVG Kruti Shreni: Volume 5 (Govt of Karnataka, 2013) Pg 165. The full quote is as follows:

“Unless there is beauty and dynamism in administration, all legislative books are mere paper-flowers.”

[2] Nani A Palkhivala: We the People. The full quote: “the feeling of obedience to the unenforceable is the very opposite of the attitude that whatever is technically possible is allowed.”

[3] D V Gundappa: Rajyashastra, Rajyanga—DVG Kruti Shreni: Volume 5 (Govt of Karnataka, 2013) Pg 129. Emphasis added.

[4] Ibid 130

[5] Ibid 131

[6] Lee Kuan Yew: Interview with New Perspectives Quarterly, 1995

[7] D V Gundappa: Rajyashastra, Rajyanga—DVG Kruti Shreni: Volume 5 (Govt of Karnataka, 2013) Pg 111.

[8] Paul Johnson: Intellectuals, Harper Collins, 1998. Pg 26. Emphasis added.

[9] Ibid, Pg 110

[10] D V Gundappa: Rajyashastra, Rajyanga—DVG Kruti Shreni: Volume 5 (Govt of Karnataka, 2013) Pg 110.

[11] Bhagavad Gita: Chapter VI: VI

[12] Ibid, Pg 145