Preface

Our present age can be accurately characterized as one of rapid technological change and an overwhelming—and almost indispensable— dependency on machines and massive information overload. This phenomenon is unprecedented in the annals of human history. But the more significant part is the fact that this phenomenon—which can be termed the Regime of Technology—has spared no nation and no corner of the earth including India.

In spite of this, the role, place and reverence for Go-Maata, the cow continue to endure as one of the central and sacred pillars of India’s ancient unbroken civilizational and cultural ethos. It is also the main reason for including the protection, nurturing and preservation of the cow—generally speaking, cattle—in the Constitution of India. This reverence for the cow in the Hindu ethos also comes in direct conflict with and has given rise to endless and fierce debates and battles over cow slaughter by those who regard it only as food.

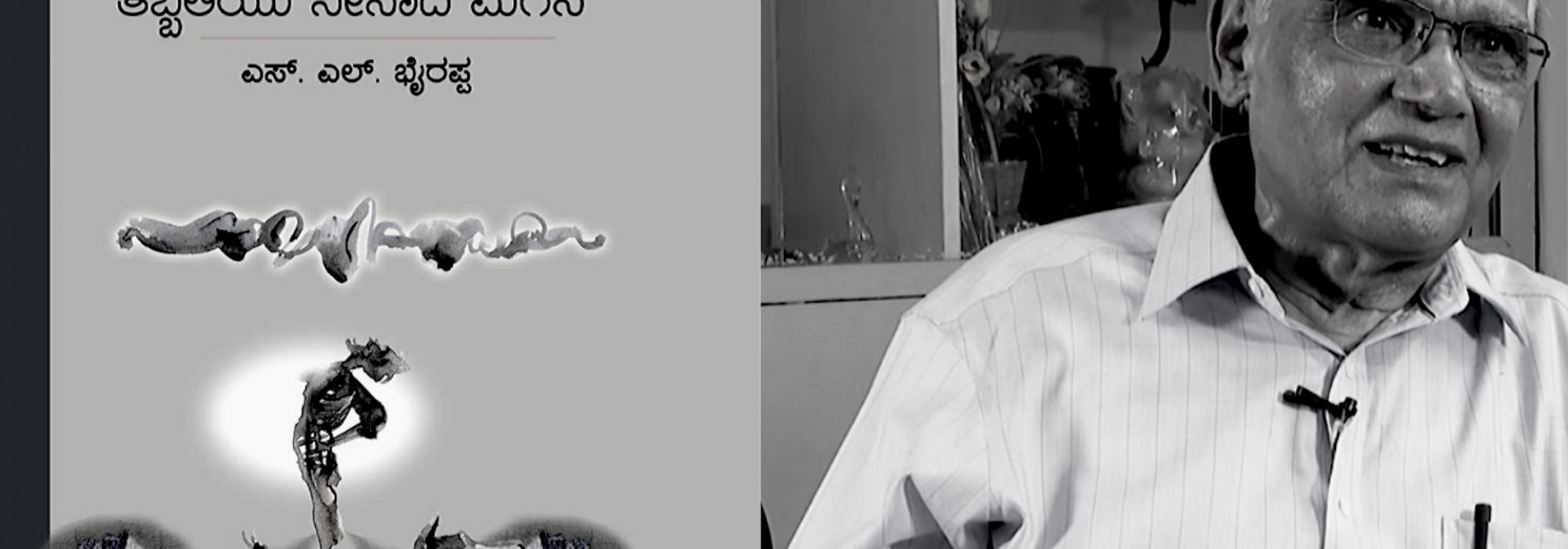

Dr S.L. Bhyrappa’s novel Tabbaliyu Neenaade Magane (literally, “My son, you’re orphaned) deals with these issues, among numerous other fundamental questions and problems. The context for the novel is set by the celebrated Kannada folk song titled Govina Haadu or ‘Song of the Cow’. Using this song as a backdrop and undercurrent of sorts, the novel obliquely explores the roots and innumerable facets of India’s culture. The song itself belongs to unknown antiquity and became popular sometime around the fifteenth century in the NaDugannada, or Middle Kannada, period of its history. It is composed in an easy, versified form employing simple language, and continues to remain an immortal cultural and literary heritage of the Kannada language. Until a few decades ago, it was compulsory for primary and middle school children in Karnataka to memorize this song. It has also found its way into films, and is the subject of numerous learned treatises and commentaries.

The gist of the Song of the Cow is rather straightforward. A cow named Punyakoti is part of a large herd of cattle owned by a cowherd called Kalinga Gowda or Kalinga Golla (cowherd). Punyakoti abides by the lasting values of truth, non-violence, compassion and dharma. One day as she goes grazing on Arunadri Hill, she’s accosted by a hungry tiger who wants to eat her. She pleads with him saying her infant is hungry and that she will feed him one last time and return. After much persuasion, the tiger is convinced by her fidelity to truth and lets her go. After she returns to the cowshed and feeds her infant calf, she informs him that she has to go back to the tiger. When the infant tries to dissuade her, she tells him it’s wrong to break the word that one has given and tells him the value of pursuing truth for its own sake. When she’s bidding him her final goodbye, the memorable line, “Tabbaliyu neenaade magane” occurs in the song. This line is the title of Dr S.L. Bhyrappa’s novel.

Punyakoti returns to the tiger’s cave and addresses him: ‘Here, take my muscles, flesh, and the warm blood of my heart. Consume them all and be happy and live well on this earth.’ The tiger, not only astonished at her steadfastness to truth but overcome with remorse, tells Punyakoti that he will incur a great sin if he eats someone as noble as her. He says in repentance that she is akin to his elder sister. He bids her a final goodbye and leaps to his death from the top of Arunadri Hill.

Although this backdrop is not mandatory to follow the novel, it, nevertheless, provides a cultural context to the heavily rustic, raw physical setting in which the plot unfolds as also the period in which it is set.

Inspiration and Origins

It is said a great work of literature emerges from great depth of feeling evoked typically by some external impetus. The world-renowned precedent of Maharshi Valmiki composing the immortal Ramayana as a result of witnessing the tragic murder of a Krauncha bird mating with its partner is quite popular.

A similar case can be made for the writing of Tabbali. Sometime during his years in Gujarat, Dr. S.L. Bhyrappa visited the sprawling Amul milk unit at Anand, celebrated as one of India’s great economic and social achievements. When he was shown the full process of how milk on such an industrial scale was produced, he was deeply shaken and moved. The cows had not only lost all sense of their own natural selves but were permanently alienated from it and had become akin to machines that breathe and behave like cows. Artificial insemination, the total absence of any scope for enjoying the warmth, intimacy, and deep bond of a mother with her infant, and the scientific process of milking cows using machines left Dr. Bhyrappa aghast and saddened. This is the origin of Tabbaliyu Neenade Magane, a fact that he records in his autobiography, Bhitti and vows that he would never again buy packed milk from the dairy.

That said, Tabbali is not merely a fictional, verbatim outpouring of the author’s anguished experience at Anand. Instead, like all his acclaimed novels, this too, is a work of art and properly belongs to the category of his major works such as Vamsha Vruksha, Parva, Daatu, Saakshi, Tantu and Mandra.

The fate of the cow in post-independence India—not just in Anand—but across the country is ensconced in the lineage of Punyakoti and forms a sprawling canvas on which Dr. Bhyrappa paints a vivid and detailed portrait of an impossibly complex array of subjects including but not limited to the cultural, social, economic and moral decline of Hinduism, the inner workings of the psyche of a mentally colonized people, the impact of westernization on Indians, the state of agriculture and what is known as animal husbandry (a dehumanizing term), family and community relationships, the subterranean bond between humans and animals, love and intellect, cultural clashes…Tabbali is a classic by any yardstick.

Ideological Interpretations of Literature

In the present time, it is doubtful whether the Govina Haadu poem is even prescribed in the Kannada language paper at the primary school level in Karnataka itself. A reasonable explanation for this can be the fact of the extreme politicization and ideological tinting of almost all aspects of our public and private lives. While one cannot draw a direct correlation, there is definitely a logical case to be made for a certain tinge of interpreting the Govina Haadu, the Song of the Cow. A good representative of this interpretation is by the Kannada academic, Mogalli Ganesh who argues that the entire song itself stands for what is pejoratively known as Brahminical supremacy with the cow as one of its key symbols. Accordingly, the tiger showing remorse and committing suicide is interpreted as the Brahmins depriving the food of the oppressed classes. To put it mildly, this sort of interpretation eminently qualifies for ideological politicking in literature and bolstering the same caste-based narrative that this ideology claims is its aim to destroy. And when this ideology acquires actual political power, it naturally erases poems like Govina Haadu from school books, a phenomenon we’re widely familiar with.

On the brighter side, such interpretations also offer a great contrast by themselves as to how ideologies constrict and stunt a human’s potential for true growth. Growth in the real sense—at least at the intellectual level, growth can be defined as constantly dilating one’s mental horizon and the willing suspension of one’s ego so that it allows itself to be challenged with new and unfamiliar ideas, to soak and absorb and expand.

To a fine artist like Dr. S. L. Bhyrappa, Govina Haadu reveals itself as both a motif and an inspiration for a profound literary and philosophical exploration. The contrast is rather straightforward: while Dr. Bhyrappa attunes himself to the spirit, ideologues detect nonexistent politics in a children’s song.

From a tangential perspective, Tabbali is also a literary classic because it dispassionately examines the so-called cow problem without injuring either the Sanatana spirit or the western worldview. A difficult feat to attain because the author doesn’t take anybody’s side in the work but presents all sides of all arguments for those who regard the cow as sacred and for those who regard it merely as food. Culture versus slaughter. But these threads in Tabbali, powerful, thrilling and moving as they are, occur largely at intellectual level or on the polemical plane if one wants to reduce it just to that.

To be continued