In the activities related to the protection of his people, a king must only take help from people who are courageous, devoted, loyal, respected, hailing from a good family, those with health and strong bodies, good students, those who keep company of noble persons, those with self-respect, those who don’t look upon others with disdain, well-educated, experienced in worldly affairs, those with an eye on their legacy and the hereafter, those who always adhere to dharma, saintly people, and those who are resilient and stable; only such people should be appointed by the king.

To undertake a certain task, two or three people should not be appointed (i.e. only one person should be given charge of a certain activity). That will then give rise to quarrels and jealousies. Only those people are worthy of becoming an amātya (minister, councillor) who are always having an eye on ensuring that they have a good name, have self-restraint and moderation, don’t harbour any hatred against those who are competent, don’t venture into mischief or prohibited actions, never forsake dharma owing to lust or fear or greed or anger, are competent, speak little, hail from a good family and have good character, are endowed with forgiveness, and are not given to boasting.

Only those people have to be appointed as purohitas who protect the good, forsake the wicked, and help in accomplishing one’s goals. The yoga-kṣema (yoga is acquiring something or obtaining new things, while kṣema is preservation of what has been obtained) of a kingdom is in the hands of the king, while the yoga-kṣema of the king is in the hands of the purohita. If he works in alignment with the king, the people will live peacefully.

The king shouldn’t believe anyone completely; that said, if he is always suspicious, that is worse than death. Therefore a king should—as far as possible—himself keep a close eye on all political matters. He must give protection to the kośādhyakṣa (chief treasurer) of the kingdom. The ministers who desire to embezzle funds or loot the treasury will constantly trouble him. If anyone says that the treasury is getting depleted, the king must secretly consult him and get all the details. The king must clearly decide: who are the people truly devoted to me, who are the people respectful to me simply out of fear, and who are the neutral parties.

In this connection, I shall narrate an old story. Listen:

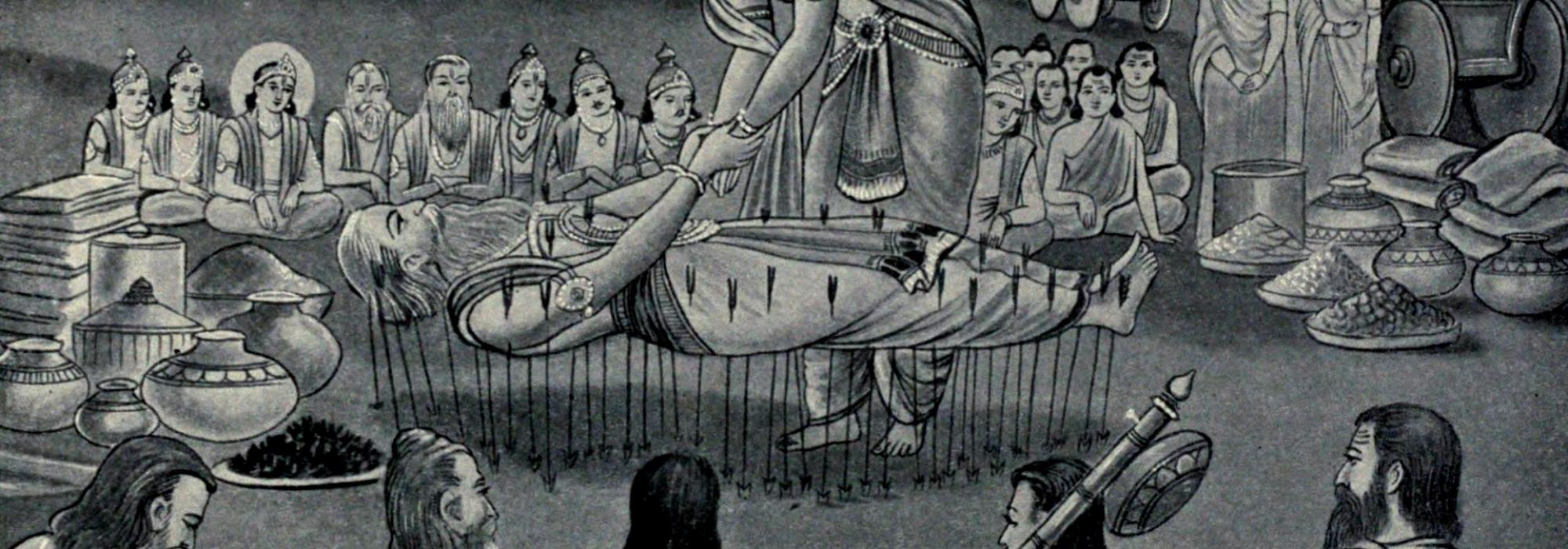

There was a ṛṣi in a forest. Owing to his gentleness in conduct, even the predatory animals in the forest like the lions and the tigers would come to him with the feeling that they are his students; they would visit him now and then to enquire after his yoga-kṣema. But a saintly dog—rather emaciated—subsisting on some fruits, roots, and tubers, would always lie at his feet, forever devoted to him. One day, a hungry leopard came there and wanted to eat the dog. The dog told the ṛṣi, “Lord, please protect me from this leopard!” At that point, the ṛṣi made the dog into a leopard. When the attacking leopard saw a creature identical to itself standing ahead, it remained silent. After a while, a hungry tiger came chasing it. Then the ṛṣi made the leopard (i.e. the dog) into a huge tiger. At that point, he lost the fear of the tiger alright but he also lost the taste for roots and tubers. He began killing and eating deer, after which he would lie down outside the door of the ṛṣi’s hut. Once when an elephant in rut attacked the tiger (i.e. the dog), he was afraid and rushed to the ṛṣi for help. The ṛṣi made him into a huge tusker. Now he drove away the elephant in rut; he began roaming about in lotus ponds and gambolling in the forests. When a lion chased it, the ṛṣi made him also into a fierce lion. After some time a śarabha came to eat the lion, upon which the ṛṣi made it into a śarabha. Looking at this, the other śarabha ran away. Overcome by mortal fear, not a single animal would go near the śarabha. Although extremely powerful in strength but weak and petty in mind, the thankless sharabha desired to eat the ṛṣi. He learnt about it through his power of tapas and cursed the śarabha saying, “You were a dog and out of compassion, I made you a leopard. Then I made you a tiger, an elephant, a lion, and a śarabha; but you sinner, you desire to eat me, who is free from sin; become a dog once again!” And thus the śarabha became a dog once again and it came to the ṛṣi seeking pity. But the ṛṣi drove him away from the hermitage.

Therefore a king has to examine the character, cleanliness, learning, circle of friends, family background, strength, and many other parameters before appointing them in powerful positions. There is no joy or comfort in getting close to someone who doesn’t hail from a good family. If the king increases the political power and clout of someone not from a noble family, such a person himself will become an enemy. Even if the king were to scold a scion of a noble family, such a person will not commit a sin. The king has to obtain victory only through the means of dharma. He has to fill his treasury. War is not wrong. Just as it is important to protect the good people and those who adhere to dharma, it is equally important to punish the wicked ones who violate dharma. Taking off the husk is only beneficial to the grain, not harmful to it. It is adharma for a kṣatriya to die when he is lying comfortably on a bed. The world is protected by a brave hero; just as a father holds the child securely on his shoulders, the brave man bears the burden of the world. However, when victory is uncertain, one shouldn’t start a war mindlessly. If it is possible, one should defeat the enemy using sāma (reconciliation, peace talks), dāna (offering incentives, bribes), and bheda (creating divisions in the enemy ranks, sowing seeds of suspicion). If it becomes necessary, just like a reed in a flood, one must bend and bow; that is also niti. Whatever be the case, one needs intellect. Manu says, “Intellect is the fundamental requirement for victory.” The work of the intellect is supreme; the work of the arms is middling; the work of the legs and the shoulders is the lowest.

To be continued…

This is an English translation of Prof. A R Krishna Shastri’s Kannada classic Vacanabhārata by Arjun Bharadwaj and Hari Ravikumar published in a serialized form.

The original Kannada version of Vacanabhārata is available for free online reading here. To read other works of Prof. Krishna Shastri, click here.