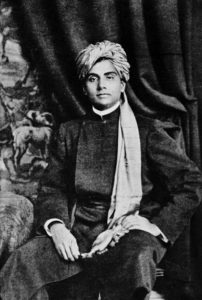

In 1906 or 1907 Swami Abhedananda honored Bangalore by his visit. He was one of the direct disciples of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. During his visit to the Unites States, Swami Vivekananda lit the lamp of Hinduism’s glory. He brought immense respect to our country in all corners of the Western world. Then he returned to India. It was Swami Abhedananda who continued Vivekananda’s work in the US and by his persistence succeeded in taking the mission forward. Was it surprising that people regarded the visit of such a great personality as a huge blessing? Special arrangements were being made to welcome Abhedananda to the city. Many people worked with great enthusiasm at the welcome event including luminaries of the city like M A Naranayyangar, who was the teacher to the crown prince of Mysore and who subsequently took the name Srinivasananda after renouncing family life, Dr. Venkatarangam of Halasuru, and the then Sanitary Commissioner Dr. Palpu.

I too was blown away by those winds of enthusiasm. But I lacked the wealth needed to give shape to my enthusiasm. I was a boy, and more than that, poor. In spite of – or perhaps because of – that, my thoughts went in a strange direction. In those days, the learned people were fascinated by English. The emotions that arose in their hearts were a result of contact with the English language. ‘As nicely as English agrees with those emotions, Kannada cannot suit them’ – such was the common opinion. Quite a few were affected by the craze of composing poetry in English. By some means, I was also affected by that madness. Of the few poems I had read in English, I was greatly impressed by the American poet Longfellow’s poem praising the altruism of the nurse Florence Nightingale. I have completely forgotten the poem now. But at that young age, I had a great weakness for composing poetry in the same poetic meter, the same simple and elegant style as Longfellow. The visit of Abhedananda provided some fodder for that weakness. I wrote a short poem in English in the form of a welcome ode, on the triple theme of greatness of Vedanta, ideals of Vivekananda, and the dedication of Abhedananda. I then had the idea of getting it published. I showed that childish creation to a few friends and well-wishers. They told me that Bangalore had only three people who could critically review English poetry and certify it to be competent –

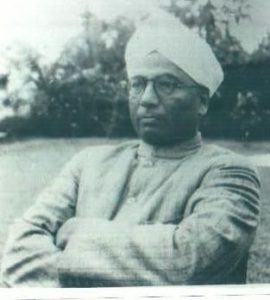

- Headmaster of the London Mission High School, K. Ramachandra Rao, B.A.,

- English Lecturer at Central College, K. A. Krishnaswami Iyer, B.A., and

- A law student, M. G. Varadacharya, B.A.

My friends suggested that I should get my poem whetted by at least one of these three and then I could get it published. They assured me that all three were good human beings and would be kind enough to review my work.

As per their suggestion, I first visited K. Ramachandra Rao. In those days, he lived in a house that was in the middle of the Eastern row of houses in Appajappa Agrahara in Charamajpet. It was about 3 in the afternoon when I went there. The moment he saw my face, he must have thought I was a student. He called me inside with respect. I went inside to find a room that had two filled bookshelves, a table, two chairs, and a plank of wood serving as a cot. He courteously pointed to a chair and said, “Please sit down.”

I sat down on the cot and explained the reason for my visit in great detail. Ramachandra Rao asked me about the extent of my formal education and that of my knowledge of poetry. Then he asked me to show him my poem. I was rather embarrassed as I handed him the piece of paper. He could have been disgusted by my handwriting itself. If someone said that my writing was akin to a hen’s leg scratching the mud, it wouldn’t have been incorrect. As for Ramachandra Rao, he read the poem from beginning to end with a smile on his face. Then he picked up a pencil and read it again. At places, he stopped to make pencil marks on the paper. As he made the corrections, he mentioned that those were places where the constructs were fragile and needed repair. He read it all over again a third time. He made some more pencil marks as he read it.

“Your ideas are interesting but your grip over the language is loose in places. If the sentence construct can be made simpler, it will be more beautiful. Show this to Krishnaswami Iyer. He will correct it. If he is impressed, all the learned folk will accept your poem. He is a good person. You can go to him without any reservations.” Thus he encouraged me. Subsequently, I visited Krishnaswami Iyer. Whatever Ramachandra Rao had said about Krishnaswami Iyer was absolutely true – this I realized. However, that episode will find its way in another story.

This is how I first came to know Ramachandra Rao. Soon our acquaintance matured. Ramachandra Rao often wrote poems in English. Every time he composed a poem, he would call for me, read out his composition to me, and explain it. Of all his writings, what I found to be most valuable was his piece titled “The Hindu Widow.” It describes in a heart-wrenching manner the inner turmoil and the external hardships of Hindu widows. That piece had been published many years before I met him. While publishing it, he had used his family surname – R S Bhuvanakar.

Ramachandra Rao was the headmaster of the London Mission High School. Today, the same building is used by the government-run Central High School. The district office lies to the north of the building and to the west we find the Mysore Bank and the Hanuman temple. London Mission High School was a famous institution of those days. It was one of the public centers of the city. In the premises of the school, perhaps every week, excellent public lectures would be organized. It also served as the workspace for the student’s group known as Mitra Mandali (‘Friends’ Group’). Then the London Mission School joined with the Wesleyan School and was re-christened United Mission School. The main subject that Ramachandra Rao taught was English literature.

In every public assembly and at every public ceremony, Ramachandra Rao would be seen in the first row. He was given that honour due to his simplicity, compassion, and mastery over speech. His style of oration in English was scholarly and entertaining because of his gentle words, saying neither more nor less than what was appropriate, a heart-touching simplicity, and dignity. All decent words; construction of sentences adhering to grammar; clarity in diction; a rich voice that was neither too loud nor too soft – these were the external qualities of his oration. And to speak of the intrinsic quality, it was the strength of his devotion to the subject. Ramachandra Rao had a deep interest in all issues related to the development of our society. Primarily education, literature, cleanliness in society, the attempt at economic prosperity – these four disciplines largely were of interest to the patriots of the yesteryears.

Among the colleagues of Ramachandra Rao in his public life, the names of a few important people are memorable – Retired Sub-judge Sulikunte Varadaraja Iyengar; his eldest son, Advocate S. Venkatachala Iyengar; Editor of ‘Mysore Standard’ and ‘Nadegannadi,’ M. Srinivasa Iyengar; Bellave Somanathaiah; the founder of the orphanage in Basavanagudi, C Venkatavarada Iyengar; and Advocate Saligrama Subba Rao. Ramachandra Rao and his friends established an organization called the Indian Progressive Union. He was one of the directors. On behalf of the organization, starting in 1905, he brought out a monthly magazine in Kannada called Hitavadi (‘Well-wisher’). Biographies of greats, well-meaning essays, extracts from treatises of various languages, historical episodes, positive news from current affairs, and several entertaining topics were published in that magazine. I began reading that magazine when I was student in Lower Secondary and I used to look forward to it with curiosity all through its publication life. I felt that the magazine’s language style was excellent. Those who wrote for the magazine explained their chosen topic with great simplicity, used few words to detail the subject matter without ambiguity, and inspired the readers to think about the topic further. The writers of Hitavadi played an important role in bringing to attention the failings and shortcomings seen in our social establishment. They brought a new perspective to old questions. By means of their debating skills, they would strike on the awareness of people and bring their attention to an injustice or an aberration that was lost in the veil of familiarity. The kind of social work – the awareness-building to cleanse society – done by Hitavadi has never been done by any other Kannada magazine; this I can declare without hesitation. Ramachandra Rao was one of the four or five people who supported this.

Apart from the monthly magazine, the Indian Progressive Union also published small books. The aim of these small books was to spread awareness among common people about topics of social reform like fighting child marriage, encouraging widow re-marriage, etc. At frequent intervals, the Union would organize friendly gatherings. In memory of great social reformers like ‘Raja’ Rammohan Roy, Ishwarachandra ‘Vidyasagar,’ and Ranade as well as to commemorate the anniversaries of laws such as the abolition of sati, abolition of child marriage, and encouragement of widow remarriage, the Union would arrange public lectures; it also arranged friendly discussions and debates on these topics. Ramachandra Rao had a vital role to play in the organization of all this.

The Indian Progressive Union was an organization that primarily focused on education, culture, and cleansing society; it did not enter much into politics. Thus it obtained some support from the education department – this is what I have heard. But the ones who encouraged this organization far more were luminaries like Diwan V. P. Madhava Rao and Councillor K. P. Puttanna Chetty. Both of them greatly respected Ramachandra Rao. In fact, I was introduced to both of them, thanks to Rao. I had written a biography of Diwan Rangacharlu sometime around 1910. Rao was greatly pleased and proud of my work. He praised me at whim. One such occasion that is so fresh in my memory – as if it happened a moment ago – was the morning when he excitedly dragged me to Puttanna Chetty’s house and with great pride sang my praises. That one episode highlights his magnanimity and his complete lack of jealousy.

Ramachandra Rao was a person whose learning was amalgamated with worldly life. Among his many interests, music was one. Those days in Bangalore, there was a music organization called Ganavinoda Sabha (‘Joy of music assembly’). Ramachandra Rao was one of its founders. He was deeply interested in music.

In English literature he had a nuanced interest. He was the one who first showed me the way to read Shakespeare’s plays and the beauty of Milton’s poems. I clearly remember him encouraging me to read two of Shelly’s poetical works – Cenci and Epipsychidion. He had a wonderful collection of books. From his library, I borrowed and read ‘Up From Slavery’ by the African-American writer Booker T. Washington, the novel ‘British Barbarians’ by Grant Allen, and many other books. Speaking from experience, I can say that he had a high degree of literary perception.

In those days, there were several factions in politics. However, Ramachandra Rao was equally respected by all political factions. The way he was dear to Diwan V P Madhava Rao, the same way he was dear to Sir P N Krishnamurti (Diwan Purnaiah). Thus it was the glory of his learning and his simplicity that gained him respect irrespective of the political faction.

Ramachandra Rao was the first friend of poor students. Like Venkatakrishnaiah of Mysore, K Ramachandra Rao of Bangalore was dear to all students. There was no limit to his help to poor students – paying their fees, buying books and clothes for them, feeding them, and recommending them for freeships and scholarships. He would not only write letters of recommendations but would himself visit houses of friends and well-wishers to put in a word. He arranged for private tuition and timely meals for several students. I was one of them.

London Mission School, which had designated him as their headmaster, showed genuine respect and gratitude towards him. His students often praise his method of teaching. He was not one to enter the classroom without fully preparing for the lesson. And as for matters of time or discipline, he was not to violate the rules. It seems that he would discipline the unruly boys solely by his warmth and kind words.

Right Honourable V S Srinivasa Shastri was a childhood friend of Ramachandra Rao. They studied together in Kumbakonam. When Shastri would visit Bangalore, he would never return without having met his childhood friend. They would be satisfied only if they spoke for a few hours.

Although Ramachandra Rao was loved by everyone and was highly influential, he never did anything that was self-serving. Leading a life of middle-class poverty, he spent his days thus till the end. But if someone sets out to write the history of Bangalore’s public life in a unique way, Ramachandra Rao’s name will be written in shining letters. How was public life seventy or eighty years ago – there is no way for me to know. But forty-five to fifty years ago, we had public life; it was pure, dignified, rewarding; even then, we had people who concerned themselves with people’s welfare; the result of their toil of old has laid the foundation for today’s public life – Ramachandra Rao’s pure and auspicious life bears testimony to this fact.

This is the first chapter from D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 1) – ಸಾಹಿತಿ ಸಜ್ಜನ ಸಾರ್ವಜನಿಕರು. DVG wrote this series in the early 1950s.