There are many works in Sanskrit claiming Kālidāsa to be their author. However, after critical analysis, scholars are unanimous in crediting seven works to Kālidāsa. We can take a brief look at each one of them.

1. Ṛtusaṃhāram

This is a small work describing the six seasons – grīṣma (summer), varṣā (monsoon), śarat (autumn), hemanta (pre-winter), śiśira (winter), and vasanta (spring). The features of each of the seasons are described in detail along with their impact on the dress and lifestyle of the people. It is believed to be the earliest among all of his works.

2. Meghasandeśam (or Meghadūtam)

This is rightly considered to be a literary masterpiece. The subject of this work is a yakṣa, a superhuman, whose superhuman powers are snatched away by his master Kubera and is banished to earth for a year. The yakṣa will be spending that time in the mountains and hermitages of Rāmagiri pining for his beloved wife. There, on the first day of āṣāḍa, he sees a cloud looming. He imagines it to be a messenger that can deliver a message to his wife when it reaches Alakāpurī, the town of the yakṣas in the lap of the Himalayas. The message and the route to be taken to deliver that message is the subject of Meghadūtam. In this work of about 115 verses, Kālidāsa has created a world fit for the gods. He describes everything in the path of the cloud – rivers, trees, flowers, cities, temple-towns – and relates each one of them to the cloud in an intimate way. The rivers in the path of the cloud become the heroines waiting for their hero, the cloud. The mountains in the path become the friends inviting the cloud to take a day’s rest. The high-flying rājahaṃsas become the companions of the cloud. The lightening of the cloud becomes a source of light for ladies venturing out in the night to meet their lovers. The thunder becomes the ceremonial drum in the evening pūja of Lord Mahākāla at Ujjain. The cloud, upon entering the province of Kailāśa in the Himalayas, changes shape to serve as steps for the cosmic couple, Lord Śiva and Goddess Pārvatī. And finally, the cloud shall reach Alakāpurī and deliver the message to his sister-in-law. We are not told whether the cloud does indeed reach there or whether it delivers the message. Essentially, this work is symbolic of our desires taking wings and going on a dream journey. The great commentator, Mallinātha Sūri exclaimed that his life was spent in understanding and appreciating Meghadūtam.

3. Raghuvaṃśam

Indian literary tradition recognizes this as the greatest work of Kālidāsa. It is the largest of Kālidāsa’s works and has nineteen sargas (chapters, cantos). It deals with the kings of the solar race and the way they lived. Through the many kings of this race, Kālidāsa expounds his lofty yet beautiful ideas. The most famous king of this race was Lord Rāma. Hence, the Rāmāyaṇa becomes the centre of this epic poem. He acknowledges this with reverence in the early part of the work. Even in the later part of the work, he pays glowing tributes to sage Vālmīki for being ‘the poet.’ Kālidāsa is clever not to get into too much detail about the Rāmāyaṇa. Instead he employs his creativity in describing the forefathers and successors of Rāma. Since the foremost among Rāma’s forefathers was King Raghu, this illustrious race also came to be known as ‘raghuvaṃśam’ or ‘The Lineage of Raghu.’ The epic poem starts off with King Dilīpa, the father of Raghu. Then come Raghu, Aja, Daśaratha and Rāma himself. The epic poem then deals with Rāma’s son Kuśa and his son Atithi. A number of less important kings get a passing mention. The last great king described is Sudarśana. After him, the glory of the race is destroyed by Agnivarṇa, the irresponsible and immoral son of Sudarśana. Thus ends the great race that boasted of people like Raghu and Rāma. The message of the epic is subtle yet powerful – great institutions built over generations can be destroyed by one irresponsible individual with great powers. If great power is not alloyed with great responsibility, it is sure to cause disasters. This is the reason why Kālidāsa chose a lineage of kings to describe his lofty ideas. The society at large derives its morals and ways by the kind of rulers governing it. If the rulers of the land set high standards, the people will automatically follow them. Thus, this work is at once entertaining and educating. That is the reason it is the book of choice for beginners as well as scholars in Sanskrit.

4. Kumārasambhavam

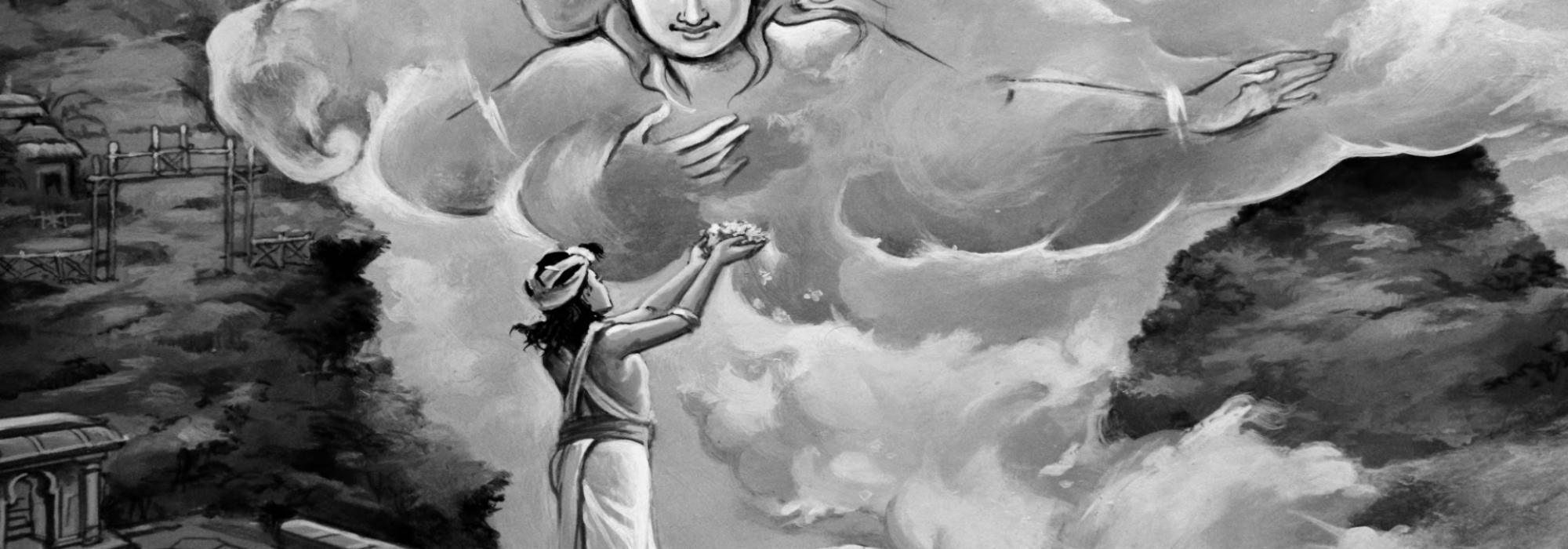

This is probably the most unique mahākāvya in Sanskrit literature. It has the style of a narrative poem but the pace of a movie. And yet, every scene is exact and intricate, as though it is a master painting. It is an exquisite painting as well as an intense movie all at once. This is probably the ideal that every literary work should aspire to reach. Mere mortals like us can only speculate at the great skill that made this possible. That such remarkable ability was employed to describe the marriage of Lord Śiva and Goddess Pārvatī is all the more elevating. This work is eight sargas (chapters) long. It starts with the description of the Himalayas and moves on to describe the birth of Pārvatī and her evolution into a beautiful young woman. She aspires to win over Lord Śiva by her beauty. Her father, the mountain-lord Himavan, also wants her daughter to marry the Lord. To this end, he appoints Pārvatī to assist Lord Śiva in his penance at his Himalayan abode. Pārvatī will be expecting Lord Śiva to get attracted to her. But mere physical beauty cannot win over the great Lord Śiva. At this time, the gods are oppressed by the demon Tārakāsura and according to Lord Brahmā, only the son of Lord Śiva shall be able to kill the demon. Lord Indra decides to attract Lord Śiva’s attention from penance to the beauty of Pārvatī. He employs the god of love, Kāma, to do this. Kāma, with his friend Vasanta, tries to induce love in Lord Śiva at an opportune moment. But Lord Śiva, despite getting distracted for a moment, regains his composure and burns Kāma to ashes. He leaves his Himalayan abode without giving any attention whatsoever to Pārvatī. Then Pārvatī decides to take the way of penance to win over Lord Śiva. The Lord, impressed by her penance, visits her āśrama in the guise of a young vaṭu or brahmacāri. He tests the love of Pārvatī in many ways. Just when Pārvatī is about to take leave of the vaṭu for his uncharitable remarks about Lord Śiva, he appears in his true form and presents himself at Pārvatī’s service. Later, the marriage of Lord Śiva with Pārvatī is formally handled on behalf of Lord Śiva by the saptaṛṣis along with Arundhati. The marriage of Lord Śiva and Goddess Pārvatī happens according to prescribed rituals with Lord Brahmā himself serving as the purohita (preceptor). The work ends with Pārvatī bearing a child in her womb. The message of the work is that true love transcends mere physical beauty. Instead, it is a happy situation where two individuals discover that they share the same lofty ideals. And hence, Lord Śiva, who does penance despite having everything, marries Pārvatī, who renounced everything she had, for the sake of penance. This was the work that probably elevated Lord Śiva to the same pedestal that Lord Rāma and Lord Kṛṣṇa were elevated to by the great sages Vālmīki and Vyāsa respectively.

To be continued.