A Summary of our Productions

The following is an overview of our productions.

Bhāminī was our first production and I conceived it based on the concept of the aṣṭa-nāyikās as present in the Nāṭyaśāstra. There is hardly any storyline in this production. The reason for not including much of a storyline is the following: if much energy and time gets consumed merely to narrate the story, there will hardly be any energy or time left to get into the details of the emotions of the character. The following view of Kuntaka has always been our guiding light:

Niranta-rarasodgāra-garbha-sandarbha-nirbharāḥ|

giraḥ kavīnāṃ jīvanti na kathāmātramāśritā|| Vakroktijīvita 4.13

Moreover, we wanted to breathe fresh air into Yakṣagāna. The best form of art unravels itself when the citta-vṛttis themselves become the itivṛttas. We also wanted to elevate śṛṅgāra from the physical plane to the emotional plane. Śuci (purity) and ujjvala (brilliance) are synonyms for śṛṅgāra and we wanted to bring them in our presentations. I have always wanted to compose poems that can bring out all the subtle beauties of śṛṅgāra. We did not want to limit the female characters that come as a part of bhāminī to any of the purāṇic or historical characters. We did not even claim to have taken the contemporary woman. The characters we chose were kācit, i.e., some woman. She can be any woman who has lived on earth at any place, at any time. By doing so, we achieved sādhāraṇīkaraṇa, i.e., universalization. Because of this, the same production was perceived by different connoisseurs according to their own tastes. For instance, sanyāsis found the presentation of Bhāminī to be leading to vairāgya, bhaktas found it to be filled with madhuropāsana, youngsters found their romantic lives embedded in the presentation, and businessmen found human nature reflected in the production. Though the concept of aṣṭa-nāyikās has been used in classical dance, all the dimensions of life, love, and companionship don’t seem to have been presented. The cycle of time, the ups and downs in life, varying intensities of love and the dharma of a married couple are amongst the aspects we addressed through the production. Because we had all these elements in our conception of Bhāminī, several dancers also found our presentations to be valuable. They watched, enjoyed, and had a lot to learn.

The setting of the story of Bhāminī is an Indian village and all events portrayed occur within the span of a day – twenty-four hours. It starts early one morning and ends the following morning. However, the storyline and emotions depicted transcend space and time. In fact, there is no distinction of gender as well. We chose the strī-veṣa simply because it has more possibilities for elaboration of śṛṅgāra, naturally goes well with āṅgika-lāsya and allows for the inclusion of many creative sancārīs. As compared to the puruṣa-veṣa, the strī-veṣa has much more possibility for ornamentation and embellishment. It is for this reason, Bhāminī was chosen to be a woman.

Bhāminī is the story of our own lives. Our desires, successes and failures, highs and lows of our moods are all captured here. All of us are bhāminīs in one sense or the other. (The word bhāminī refers to an irascible and impatient woman). We are all under the mercy of our desire-husbands, who at times cater to our emotions and at other times fail to do so. We fight with our desires – sometimes win and sometimes lose. There is scope for evoking all the nine rasas here. When our desires are fulfilled, it leads to śṛṅgāra, hāsya, or adbhuta. When they fail us, it leads us to karuṇa, vīra, raudra, bībhatsa, or bhayānaka. Śānta is inherent in all these emotions. This can easily be correlated with the Bhāminī production.

The heroine waits early in the morning for the return of her husband as a proṣitapatikā. She learns that he is on his way back and with much excitement, prepares herself to receive him starting from the forenoon and is now a vāsakasajjikā. By evening, she heads out all by herself to find her husband and is an abhisārikā. She comes to the saṅketa-sthala (the usual meeting spot), does not find him there, and is now a vipralabdhā– a disappointed woman. Evening slowly makes way to darkness. She is unable to make her mind to return home and waits at the saṅketa-sthala even in the dead of the night – a virahotkaṇṭhitā. Later she spots him heading back with another girl; she is angry and dejected. She rushes back home, abuses him and throws him out – she is now a khaṇḍitā. It is already post mid-night by now. Her frustration is now gone down and she feels that she did not even give him a chance to speak and explain – she feels that she mistook the other girl to be her beloved’s concubine and weeps over her behaviour; she is now a kalahāntaritā, just before dawn. Early next morning, she opens the main door of her house, finds her husband waiting there all night, shivering in the cold. He explains that the girl belonged to a respectable family of the village and that he didn’t have an affair with her. He had escorted her to safety as she was all alone and was under difficult circumstances. She takes an oath of sātivratya (loyalty to wife) from him. She has now won the love of her husband and is thrilled - a svādhīnapatikā. What is shown at the end is the manner in which there is victory in losing to your beloved. This is the dharma of companionship - dāmpatya-dharma. It is the essence of the dharma of the world. The last few words of the saptapadī-mantra – sakhā saptapadā bhava find their fulfilment here. A raw fruit ripens to be a tasty one and this is the kind of sublimation depicted in Bhāminī. The wife can even grow to be a mother of her husband. The goal of Bhāminī was to depict such subtle śṛṅgāra – one can even call it the śṛṅgāra-dharmopaniṣat.

~

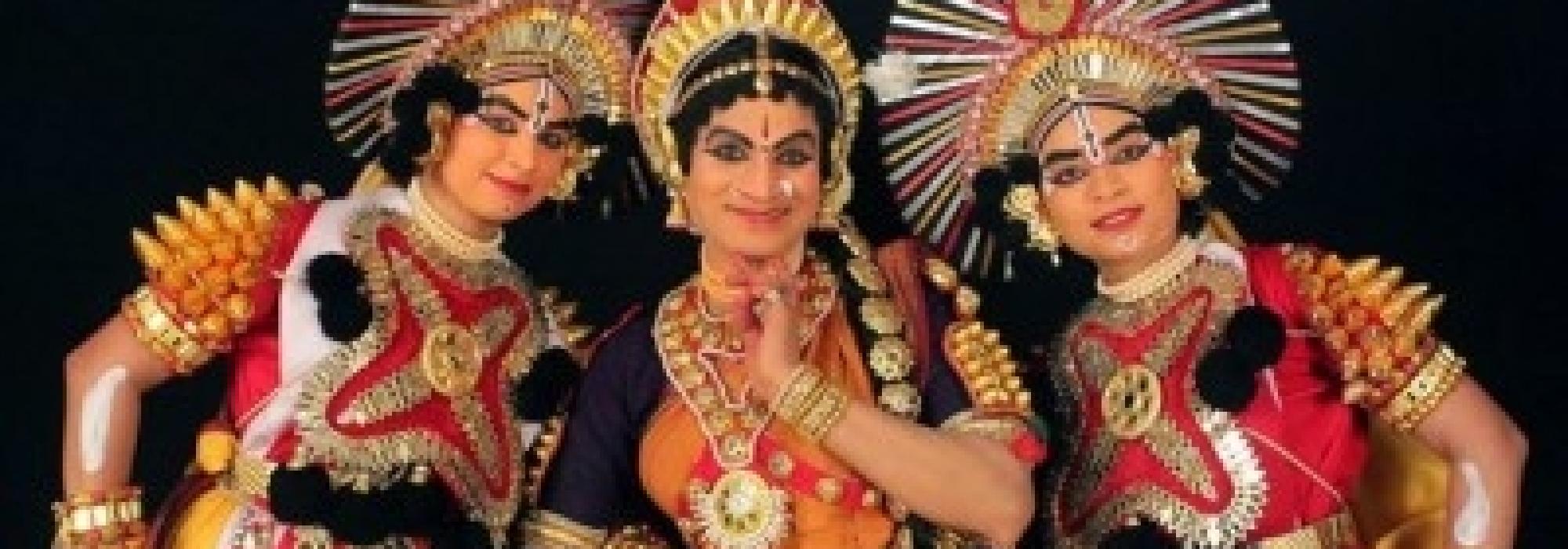

Our second production was Śrī-kṛṣṇārpaṇa. As the name suggests, it contains the stories of Kṛṣṇa taken from the purāṇas. The attempt was to establish the character of Kṛṣṇa through the eyes of three women who played major roles in his life – Yaśodhā, Kṛṣṇa’s mother, though not the biological one; Rukmiṇī, the girl Kṛṣṇa married without elders’ participation; and Draupadī, Kṛṣṇa’s sister – though not by blood but by emotion and divine providence. Through these women, we tried to depict the different aspects of Kṛṣṇa’s character – a mischievous and cute child, a sweet and understanding husband, and a protective elder brother. We attempted to suggest that sneha (friendship, affection) transcends all relationships. We also portrayed three major dimensions of bhakti – vātsalya, madhura, and sakhya. These are three paths that upāsakas (devotees) can choose from – the paths are subtly suggested in the presentation. We chose women characters who were of different age groups and societal backgrounds

~

Yakṣa-darpaṇa was conceived in an attempt to include brilliance in āṅgika and variety in nṛtta. We brought in the pūrvaraṅga tradition of the Yakṣagāna theatre and attempted to rejuvenate it to a large extent. We chose the text from the existing Yakṣagāna-prasaṅgas and showed how the same concepts can be presented in a more appealing manner. In addition, the pīṭhikā-strī-veṣa of the pūrvaraṅga was included and we added many more creative elements. We showed how the lāsya of the pīṭhikā-strī-veṣa can be made delightful and impactful. We included spoken word vācika in this presentation and so it also satisfied the audience of the traditional Yakṣagāna, who think that conversation is the defining feature of the art.

~

Yakṣa-kadamba was an amalgamation of selected sequences from the famous prasaṅgas of Yakṣagāna blended with newer compositions written for this purpose. The stories connected with Viṣayè, Dākṣāyiṇī, and Śūrpaṇakhā were picked from already existing prasaṅgas. I composed smaller scenes connected with the following characters – Rādhā (Veṇu-visarjana), Kuntī (Putra-parityāga), Pūtanā (Pūtanā-mokṣa), Ulūpī (Nāga-nandinī), Citrāṅgadā (Manipurada Māninī), Mohinī (Bhasma-mohinī), Ambā (Praṇaya-vañcita). Although these characters are popular in the traditional Yakṣagāna repertoire, they were recomposed to suit our purpose. In all these cases, we included prose conversations too, as much as the context and aesthetics would permit.

~

Jānaki-jīvana is a challenging production that portrays a single character throughout. The production has less scope for dance. The rasa taken for elaboration is not śṛṅgāra which has the potential for elaboration and interpretation; it is neither vīra nor raudra, which can lend themselves for a lot of energy and vigour. It is not even hāsya which can tickle the audience through mischief and jokes. The primary rasa of the production is karuṇa. It has been successful in capturing the audience for over two hours and has made them shed tears.

~

An artiste who has enacted in the productions Bhāminī, Kṛṣṇārpaṇa, Yakṣa-darpaṇa, Yakṣa-kadamba, and Jānakī-jīvana can successfully portray any other character. He can perform the role of any strī-veṣa very well. I would like to humbly submit this as one of the outcomes of our productions

Vijaya-vilāsa, the first of our Yugala-yakṣagāna productions is set in the backdrop of Arjuna’s tīrtha-yātrā. It depicts the characters of Ulūpī, Citrāṅgadā and Subhadrā whom he married during his travels. The production is a metaphor for the human’s travel in the material world. The manner in which the jīvātmā goes from tamas to rajas and then graduates to sattva are suggested through the three heroines in the production. Arjuna does not keep up his word and gets into trouble. This is similar to the manner in which the jīvātmā gets stuck, nay, trapped in the world. This trap is due to adhyāsa. The jīvātmā can overcome this entanglement only by attaining citta-śuddhi through loka-saṅgraha and realising the nature of eternal Joy; being inactive and inert does not help him transcend the world. This is the concept of the tīrtha-yātrā. Description of six seasons which suggests the passing of time and accounts of hunting, war, travel and water sports which suggest space are incorporated in the production. These themes are natural to Yakṣagāna and a variety of movements were incorporated to depict them. In other words, these help in establish the spatio-temporal features of the world. One can witness all the aspects of caturvidhābhinaya that is possible to be brought out in Yakṣagāna through two artistes only.

At the beginning of the production, Arjuna protects the cows of a brāhmaṇa – as he rushes forth enthused to fight a war, we have included yuddhada kuṇita. Following this, he takes leave of his elders and sets out on a tīrtha-yātrā – this is depicted using prayāṇada kuṇita. Tèrè-òḍḍolaga (tèrè-marèya kuṇita – dancing behind a screen) is performed for Ulūpī’s entry. Next comes the description of the śarad-ṛtu (autumn season) and involves lāsya. There is jala-krīḍā (playing with water) in the backdrop of Arjuna meeting Ulūpī – this is depicted by jala-krīḍèya kuṇita. Post the wedding ritual, a nāga-nartana is included, which adds beauty and entertainment. Arjuna then heads to Maṇipura and experiences hemanta (snowing season) and śiśira (winter season) – there is dance to establish these seasons as well. Citrāṅgadā is out hunting and her entry onto the stage is the beginning of a new scene in the production – she performs beṭèya-nṛtya on her entry. Citrāṅgadā is overcome with love for Arjuna, performs the manmatha-lāsya and marries him. Here, vasanta (spring season) is depicted and the couple dance together as though in a friendly competition. Arjuna bids farewell to her and heads towards Dvārakā in grīṣma (summer) – there is a dance that subtly suggests the coming of summer. This is followed by the varṣā (rainy season) and that marks the dancing entry of Subhadrā – her dance is akin to prāveśika-dhruva. Rāgas that can depict the season and the associated emotions are used appropriately.[1]

Arjuna is in the disguise of a sanyāsi and there is a satirical dance performed by him. Subhadrā is innocent and trusts him out of her naivety. There is an interest and surprising switch of costumes where Arjuna-sanyāsi changes over into Vīra-vijaya – the brave conqueror who valorously succeeds. This is an entertaining and a fresh attempt in the domain of Yakṣagāna. It can be thought of as dimension added to our Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna and a step further.

This series of articles are authored by Shatavadhani Dr. R Ganesh and have been rendered into English with additional material and footnotes by Arjun Bharadwaj. The article first appeared in the anthology Prekṣaṇīyaṃ, published by the Prekshaa Pratishtana in Feburary 2020.

[1] The rāgas Valaci and Mārubihāg are employed for the description of śaradṛtu, Māyāmāḻavagoḻa for hemanta, Śaṅkarābharaṇa and Mukhāri for śiśira, Vasanta, Basant-bahār and Mohana for vasanta, Bhūpālī and Kīravāṇi for grīṣma, Megha and Bṛndāvanī for varṣā.