We used the traditional accompaniments of Yakṣagāna, namely caṇḍè and maddalè. To enhance the melody, however, we included flute and violin as accompaniments. From the early days, I felt the need to include a svara-vādya to add to the melody of the Yakṣagāna himmeḻa. I have even spoken about this on various platforms. Shivaram Karanth, Padmacharan, Mahabala Hegade, and others were of the same opinion. Shivaram Karanth has used violin and saxophone for accompaniments. It is worth mentioning here that when I shared my thoughts with Prof. M Rajagopalacharya, he had expressed his agreement with my idea. Vidvān H S Venugopal usually provided flute accompaniment for our presentations and his presence added tremendous value for every performance. The Kanchana Sisters (Smt. Sriranjani and Smt. Shruti Ranjani) provided violin accompaniment for a few of our concerts. Their mellifluous ālāpanas added richness to bhāgavatikè.

I will need to tell something exclusively about the percussion instruments used as a part of the himmeḻa. The maddalè artiste, A P Pathak does not play the instrument looking at Mantap’s feet, but plays it by looking at the emotions on his face. Therefore, his accompaniment caters to Rasa rather than limiting itself to tāla. The muktāyas (concluding rhythmic phrases) he plays are also aesthetically appealing and add to the beauty of the song rendered by the bhāgavata. There is no competition between the artistes here. Instead, they all work together and complement each other to bring out the best effect overall.

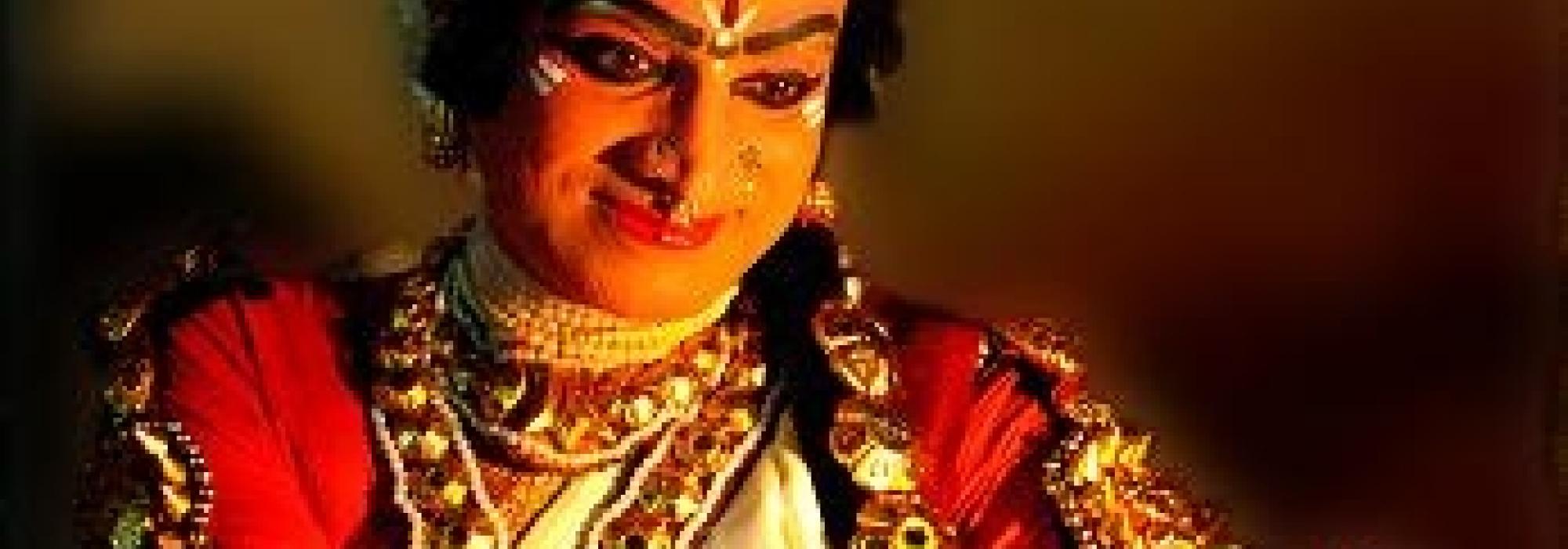

Caṇḍè is known as a masculine instrument. Idagunji Krishna Yaji plays it with such adeptness that it aptly suits the strī-veṣa. He makes his caṇḍè speak in the tone of the kaiśikī-vṛtti. He makes the caṇḍè provide its gentle rhythms throughout the performance, without disrupting the aesthetics. The soft and aesthetic usage of caṇḍè and maddalè in tune rāga and bhāva in our presentations has won the hearts of the connoisseurs.

The contribution of Vidvān Yallapura Ganapati Bhat, who has been the bhāgavata for all our presentations, is extremely important. He has two unique strengths which other bhāgavatas lack. He has mastery over Carnatic music, is intimately familiar with Hindustani music and knows the strengths and weaknesses of both the systems. This has helped him handle śruti, laya, and mūrchanā (scale of a rāga) extremely well. Sri Ganapati Bhatt learnt classical music from Matapadi Rajagopalacharya and bhāgavatikè from Neelaavara Ramakrishnayya. As he knows both the forms well, he can bring aspects of Carnatic music in an aesthetic manner in bhāgavatikè. He never dilutes the bhāgavatikè with gimmicks and ensures that his singing is full of life. He constantly contemplates upon the various possibilities of every rāga. Therefore, there is no dearth of variety in his singing. He can sing continuously for two hours, render thirty to forty rāgas with all their nuances, and closely follow Mantap’s spontaneous abhinaya. This is an unimaginable task and is of a unique nature, at least as far as Yakṣagāna is concerned.

Traditionally, the music that accompanies Yakṣagāna does not have svara-kalpana. Those with conservative minds even brush it aside calling it non-traditional. Their stance is not an objective one – they are motivated by personal biases. Moreover, much of their opposition is because of their inabilities and lack of wisdom. All tiṭṭus (genres, regional styles) of Yakṣagāna have the tradition of reciting biḍtigès and dastus (reciting purely rhythmic patterns at length); while doing so, in many cases, the bhāgavata and the maddalè artiste engage in a competition of savāl-javāb. The Nāṭyaśāstra has provided us with a bounty of śuṣkākṣaras (purely rhythmic syllables) that can be used for rhythmic patterns. On similar lines, why would we be deviating from tradition if we were to use svaras, which are softer and more melodious than the jatis (dastus)? Music that employs soft notes will admirably suit strī-veṣa. In our performances, we bring in both jatis (dastus) and svaras. Many have displayed displeasure about our attempts at introducing these changes –it is often because of their blind adherence to what they believe is tradition and sometimes it is because they cannot bring such beauty in their art.

Many oppose bringing in rāgālāpana in Yakṣagāna presentations – this is because of their lack of awareness, shortcomings in talent and a conservative mind. It is only rāgālāpana that can work well with pure, unalloyed and impactful sāttvikābhinaya. In rāgālāpana, as rhythmic patterns and tāla cycles are absent, art transcends time. With time, space is also transcended, thereby leading us to get a glimpse of the Eternal Reality, the Parabrahma. We are lead on this path through the medium of Rasa, that is beyond the spatio-temporal framework. Art that does not reach this dimension cannot qualify as true art. Therefore, it hardly makes sense to waste our energy over tāla which is rather prosaic. In our productions, therefore, we have stressed on rāgālāpana. It is such ālāpana that helps establish the sthāyi-bhāva of different characters and also aids the artiste to step into the shoes of various characters. Sri Ganapati Bhat’s strengths have worked towards enriching bhāgavatikè in this dimension as well.

Ganapati Bhat possesses very good knowledge of literature – and that is one of his strengths. He has undergone training in alaṅkāra-śāstra in the Saṃskṛta-pāṭhaśālā in Udupi and obtained a vidvat. He can recite poems set to different vṛttas and kanda-padyas effortlessly, without yati-bhaṅga (violation of cesura). His recitation is pleasing to the ear; he is accurate in splitting words. His pronunciation of the alpaprāṇas and mahāprāṇas (soft and hard syllables) is devoid of all ambiguity. He is sure of the manner in which different syllables need to be accurately pronounced. He is also adept at in rendering songs set to different tālas and makes sure that the splitting of words is grammatically correct. Because of these merits, his bhāgavatikè is the very life of Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna.

It is my firm conviction that the bhāgavatikè must first undergo a change if we wish to bring a transformation in Yakṣagāna. The entire theatrical presentation depends on bhāgavatikè. This is true of all performing arts, particularly the nṛtya and nāṭya traditions. I, therefore, discussed in length about the bhāgavatikè used as a part of our presentations. There are many more dimensions that must be discussed. Based on the details I have presented, capable scholars and artistes can extrapolate further.

~

We now come to the last component of the vācikābhinaya – impromptu speech. This refers to the lines spoken by the artiste playing the role of a specific character. In our early presentations of Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna we did not include spoken words. The first few presentations of Bhāminī, Śrī-kṛṣṇārpaṇa, and Yakṣa-darpaṇa were without dialogues. Our Yugala-yakṣagāna Haṃsa-sandeśa was without any speech and so was the Yakṣa-navodaya of the Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna genre. Yakṣa-kadamba, Jānakī-jīvana, and later versions of Yakṣa-darpaṇa included quite an amount of speech. Although short in its length, Veṇu-visarjana is not devoid of speech. Vijaya-vilāsa too has speech in some segments. Many believed that we were sambhāṣaṇa-vairis, i.e., opposers of spoken word in Yakṣagāna! In fact, this was one of the parameters used by people to declare that our presentations could not be classified as Yakṣagāna at all. Our intention was simply the following: at instances where the bhāgavatikè can work well and communicate all that is necessary, the need for spoken word does not arise. Moreover, this being Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna, there are no other characters on stage and there’s no need to introduce conversations. It would suffice if a sentence or two is uttered in between padyas as reactions, to suggest the presence of other characters. Often even that much of speech was unnecessary. What’s more, artistes performing traditional Yakṣagāna today employ so much of speech that it feels like verbal diarrhea leading to the constipation of dance. This can even lead to unaesthetic consequences. In fact, when an artiste engages in excessive conversation, he tends to compromise upon the stylized nāṭya-dharmī and tends towards the realistic loka-dharmī. Loka-dharmī in itself is not harmful, but if the artiste is not careful, his speech may even become adharmī, i.e., unaesthetic and unethical. Artistes end up speaking out of turn and transgress the limits of aucitya of the character. They end up portraying the character in a manner that violates Rasa. One of my intentions was not to allow such defects to creep into our presentations. We used āśu-sambhāṣaṇa (extempore, impromptu speech) at several places as required by the concept and within the bounds of auctiya. Learned connoisseurs will be able to understand and appreciate the kind of speech that we introduced as a part of productions such as Veṇu-visarjana, Jānakī-jīvana, and Yakṣa-kadamba (Māyā-śūrpaṇakhā, Pūtanā and Viṣayè). The speech rendered is emotionally rich and poetic in nature. The short conversations that take place between the artiste and the bhāgavata is also worth noting. Gentle hāsya, heart-touching karuṇa, vibrant vīra, and graceful śṛṅgāra are predominant in our presentations.

~

The nirdeśaka (director) of the production speaking before and after the show can also help in Rasa-niṣpatti – evoking Rasa. Though his speech is not directly a part of the presentation, it streamlines the connoisseurs’ attention to the aspects that are important and unique. The nirdeśaka sets the context of the episode being portrayed and narrates the story in brief. The words of the nirdeśaka also work as arthopakṣepas between different important segments of the presentation. In other words, his words connect different segments and bring out certain details which cannot be aesthetically presented on the stage. Rasikas who have attended our concerts have given us positive feedback on the value added by the words of the nirdeśaka. The details provided by him in the presentation of Bhāminī are multifold. He not only talks about the progressive change of the emotion from śṛṅgāra to śānta but also about the correlation between the mental states of the nāyikā to management theories and mechanical engineering. He also relates the mental states of the heroine to everyday situations of common men. In Śrī-kṛṣṇārpaṇa, the nirdeśaka tells the audience the manner in which a cowherd boy rose to be a socio-political visionary and in Jānakī-jīvana, he describes the skill with which Vālmīki writes his epic poem and the manner in which Śrīrāma’s character plays on the life-canvas of Sītā.

To be continued...

This series of articles are authored by Shatavadhani Dr. R Ganesh and have been rendered into English with additional material and footnotes by Arjun Bharadwaj. The article first appeared in the anthology Prekṣaṇīyaṃ, published by the Prekshaa Pratishtana in Feburary 2020.