Traditional forms of dance that have their roots in the upa-rūpakas are today called śāstrīya-nṛtya. There are several regional forms of śāstrīya-nṛtya (classical dance) such as Sadir, Tāphā, Keḻikè, Oḍissi, Mohiniyāṭṭam, Kūcipūḍi, Kathak, Maṇipuri, Gauḍīyā and Sattrīya. In fact, several of these dance forms are by-products of the original theatrical traditions. Kūcipūḍi, Mohiniyāṭṭam, Sattrīya and other forms stand as examples for these. These took their birth respectively from Kūcipūḍi Yakṣagāna Bhāgavatamela, Kathakalī (Kṛṣṇanāṭṭam and Kūḍiyāṭṭam too had their influence) and Sattrīya-raṅga-bhūmi. These have no longer remained the bahuhārya-nāṭyas that they originally were and have metamorphosed into ekāhārya-nṛtya. Sthāyi-dārḍhya (bolstering the sthāyi) requires the artiste to enact a single character throughout the program or at least dedicate one full piece for a particular character. All the four modes of abhinaya will need to work together to enrich the sthāyi. Nṛtya is dynamic, in the sense that there is constant switching of characters as per the needs of the episode. Nāṭya-dharmī dominates such presentations and Sāttvikābhinaya which is rooted in loka-dharmī naturally has lesser scope. Anukaraṇa (imitation) dominates such nṛtya and there is little scope for anukīrtana (exalted imitation). It becomes more important to depict the character than to enliven it. The audience for dance must have some knowledge of nṛtya-samaya, i.e., conventions of dance. However, neither the ones initiated into such learning nor the uninitiated ones seem to derive much pleasure out of such dance presentations. To compensate for this, nṛtta (pure dance) that involves non-representational and non-narrative movements, is introduced in classical dance presentations. Further, sancāris and the play of svara and laya bring variety to dance. As artistes have realised that it would be difficult to portray too many characters with the same intensity at all times, they tend to focus on one and peripherally touch the other characters as the context demands. Therefore, it is difficult to depict a long story with multiple episodes through ekāhārya-nṛtya. Even the episodes chosen here are popular ones and have only a few characters (and fewer major ones). They mostly contain based on abhinaya of choreographies based on nāyaka or nāyikā.

The Ekavyakti-Yakṣagāna we have devised is different from the various kinds of deśī-nṛtya and like mentioned before, is different from presentations attempted under the same name. We have retained the system of nāṭya of Yakṣagāna and more than making it congenital with any form of nṛtya. I should, however, hasten to add that it is not very easy for the Ekavyakti presentations to retain all the elements of its parent theatre.

As per my conception, the artiste remains as one character throughout the performance. In some longer presentations such as Śrī-kṛṣṇārpaṇa and Yakṣa-kadamba, the artiste performs the role of one character only in every segment. His costume suggests the character role he is playing. As he cannot switch roles, the storyline chosen for depiction should be tailored to keep the particular character in focus. Therefore, the episodes in the story will need to be thought out well and, in most cases, will need to be limited. Moreover, as we have limited ourselves to one character only, other characters need to be established through the lyrics of the song (padya, gīta) or prose conversations (gadya) with the support of the bhāgavatas. Even when speech of this kind is introduced, the artiste does not switch to another character or perform abhinaya to the particular song; he instead reacts to what he hears to establish the presence of another character. To give an example, in the production Śrī-kṛṣṇārpaṇa, the artiste portrays the role of Yaśodhā. All the mischief of Baby Kṛṣṇa is depicted only by the reactions of the mother. Similar is the episode where Draupadī is portrayed. Kṛṣṇa comes to her rescue when she is abused by Duśśāsana. Here too, the artiste remains as Draupadī and through her reactions establishes the entry of Kṛṣṇa. In the production Jānakī-jīvana, the artiste plays the role of Sītā, and all other characters such as Rāma, Lakṣmaṇa, Rāvaṇa, and Vālmīki are established by the reactions of Sītā.

At the outset it might appear that there are some shortcomings in this manner of presenting episodes because the artiste is not allowed to switch from one character to another. In classical dance presentations, on the other hand, it might appear that a lot of variety can be brought at the levels of āṅgika and sāttvika as different characters are depicted. A closer examination will reveal that establishing every other character solely through the eyes of the character that the artiste is portraying has great advantage. Instead of making things literal, there is a certain amount of suggestion that is naturally introduced by the reactions of the character that the artiste is playing – i.e., vyaṅgya always gives rise to many layers of dhvani, which vācya cannot. It is strange that several artistes have not (yet) realised this advantage in the Ekavyakti form. This form of solo Yakṣagāna focuses on depth rather than width and establishes the sthāyi-bhāva of the particular character extremely well. The pre-requisite is that the performing artiste must be highly talented and capable of bringing great intensity in the depiction of the character. Unless he has the maturity and the potential, it is impossible to perform Ekavyakti-Yakṣagāna. Mantap Prabhakar Upadhya is inherently gifted and is a man possessing great talent. Although he found it difficult to adapt to the new form in the beginning, he realised later that this was the most natural and the best medium to bring out his complete potential. He became so immersed in this art form that he started feeling the presence of all other characters in a traditional Yakṣagāna presentation to be disturbing whenever he took part in such presentations.

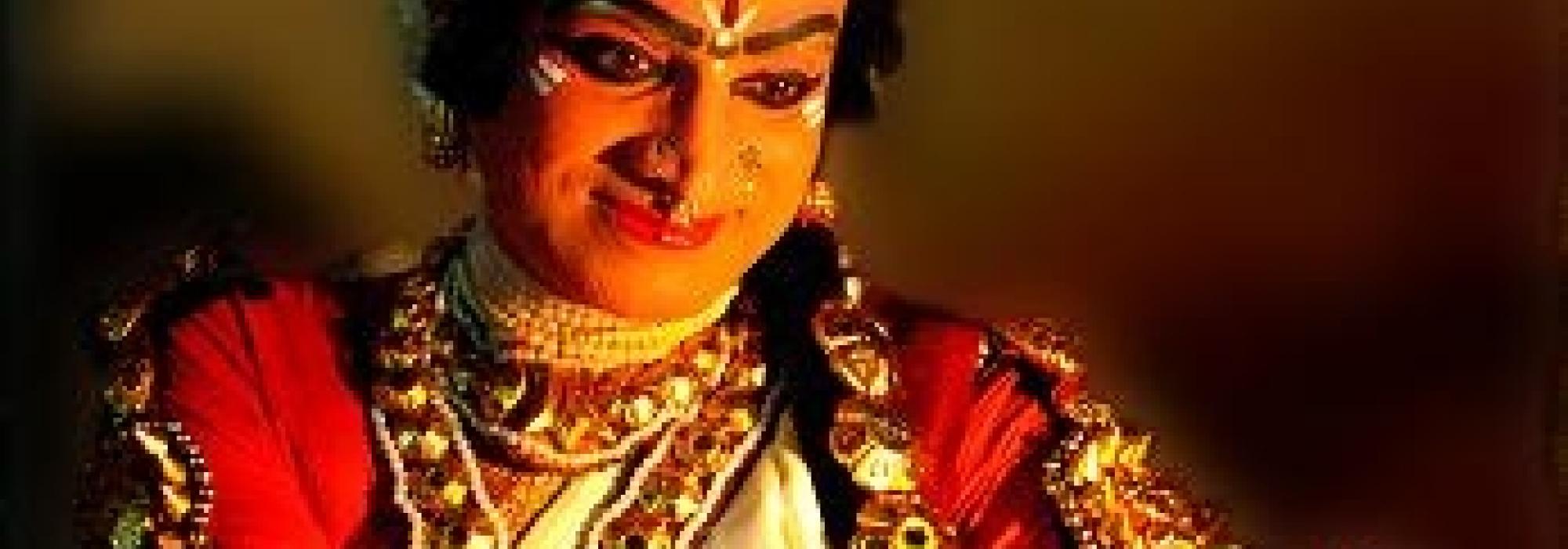

For our Ekavyakti presentation, it was necessary to take refuge in śṛṅgāra, which is hailed as the Rasa-rāja. It is only in śṛṅgāra that all other rasas find their fulfilment. To understand this, it would be a good idea to take a look at our Bhāminī and Vijaya-vilāsa presentations. This is evident even in the pieces Raṅganyātakè bārano and Viṣayè of the production titled Yakṣa-darpaṇa. It is possible to fill in a lot of details to themes that have śṛṅgāra as their fundamental Rasa. śṛṅgāra is the only Rasa that has this potential. Strī-veṣa lends itself beautifully to śṛṅgāra and no puruṣa-veṣa can compete with it. It would not be wrong to say that gadya is masculine and padya is feminine. Excessive embellishment is inappropriate for gadya – over ornamentation risks turning gadya into a parody. Also, gadya does not lend itself to be sung or enacted in slow speeds with great amount of detailing. However, padya can digest any amount of ornamentation. Further, in padya, there is much scope for intricate work both at the level of form and content. Given Mantap Prabhakar Upadhya’s preference for finesse and detailing within the framework of Yakṣagāna, it was a blessing in disguise for us that strī-veṣa suited Ekavyakti-Yakṣagāna perfectly.

Based on the discussions so far, it is rather natural for the following questions to arise. Is it possible for a solo puruṣa-veṣa to perform Ekavyakti-Yakṣagāna? Will it be appealing? While it is not impossible, this amount of detailing is certainly difficult to bring out. Too much of filigree work will look out of place in puruṣa-veṣa. Nevertheless, it is quite possible to impress the audience with a puruṣa-veṣa presentation that lasts for about an hour or at the most an hour and a half. Talented artistes can certainly try it out.

The Birth and Background of our Ekavyakti-Yakṣagāna Presentations

I had great interest in nṛtya, nāṭya, nāṭaka, and cinema from my early days. I always contemplated upon the purpose and importance of loka-dharmī and nāṭya-dharmī and their relation with svabhāvokti and vakrokti respectively. This led me to understand the correlation between mārga and deśī as well as the principles that are common to both. As I learned more and more about Nāṭyaśāstra, I realised the inherent essence and concordance of India’s regional theatrical forms. Kathak, Kūcipūḍi, Mohiniyāṭṭam <>, and Sattrīya developed as independent solo dance forms, breaking off from their parent theatrical forms. On similar lines, if we could create a solo Yakṣagāna form, it would become a first-of-its-kind solo dance form of Karnataka. However, if we were to develop this as a dance form, the strengths inherently present in Yakṣagāna will not be showcased. Impromptu abhinaya, spontaneous delivery of dialogues, and being true to the character portrayed – all this would be lost, should we employ the genre of nṛtya. This led me to decide that it was important to retain the element of nāṭya while creating a new solo form. Without capable artistes who could be part of himmeḻa and mummeḻa, this would merely be a dream! I sought the help of some classical dancers but they lacked the kind of exposure to Yakṣagāna needed for such presentations. Several dancers who practice regional classical dance forms lack a proper understanding of aesthetics, fail to look beyond tāla, and have not realised the interdependence of āṅgika and sāttvika. Besides, they have their own interests, commitments, and pursuits. In such a situation, it was Mantap Prabhakar Upadhya who stood by me.

I first met Mantap when he was a part of our Kāvya-citra-yakṣagāna program. He shared his long-cherished desire with me. “I would like to portray a strī- veṣa even when I am sixty years of age and capture the audience with the same intensity that I am doing now. The way things look today, there is no scope for artistes who don strī-veṣa to survive on the stage for too long. Much importance is given for appearance and movements, so aged artistes will not be able to pull off the character effectively. Further, strī-veṣa is a rarity in most Yakṣagāna presentations. Also, there is not much that a strī-veṣa can do on stage in the existing framework of Yakṣagāna – it is just one kind of character among several. Strī-veṣa is merely a glamour element that comes in between puruṣa-veṣas, as though to string them all together. Strī-veṣa comes on stage like a bolt of lightning and then vanishes in a second. These days, the presentation of strī-veṣa is also dictated by the whims and fancies of a few artistes. At times, feminism hijacks the presentation and although women are at the forefront, the classical nature of the feminine is lost. I wish to portray a graceful female character that is true to the nature of women. Often, if a strī-veṣa enters the stage, the spectators take a break from watching the show and head towards the tea stalls. Is there an aesthetic reply we can give to this?”

When he posed this question, I suggested that he could attempt Ekavyakti-Yakṣagāna, rich in sattva and conceived keeping only Rasa in mind. I explained the structure of the prasaṅga called Bhāminī and the manner in which it must be executed. I had composed the padyas for this prasaṅga years earlier. I was pleasantly surprised when Mantap agreed to this. He had made up his mind to try this presentation but he was not completely free of doubts. It is only when an artiste tries out something novel will his questions find answers by themselves or will get subdued in due course!

This series of articles are authored by Shatavadhani Dr. R Ganesh and have been rendered into English with additional material and footnotes by Arjun Bharadwaj. The article first appeared in the anthology Prekṣaṇīyaṃ, published by the Prekshaa Pratishtana in Feburary 2020.