Yakṣa-navodaya is an attempt at aesthetically stitching together the compositions of a few Navodaya poets of Kannada. The compositions chosen are ene śuka-bhāṣiṇi of D V Gundappa, nānu baḍavi āta baḍava of Bendre, bṛṃdāvanakè hālanu māralu of Kuvempu, nīḍu pātheyavanu of Ti. Nam. Sri, ahalyè of Pu. Ti. Na, nīvallave of K S Narasimhaswamy. The production is merely an attempt to indicate one such possibility. There is a lot of scope for imagination and for bringing out sāttvikābhinaya in the production.

~

Haṃsa-sandeśa is yet another prasaṅga created for Yugala-yakṣagāna. This starts with the episode where Nala goes for hunting and comes across a swan which acts as a messenger. The following episodes follow – Nala falls in love with Damayantī; Nala meets the devatas as he is on his way to svayaṃvara – they convince him to be their messenger; argument between Nala and Damayantī ensues in the antaḥ-pura; Damayantī makes up her mind to marry Nala; Damayantī solves the pañca-nalīya-samasyā (a challenge to identify the real Nala) and finally gets married to Nala.

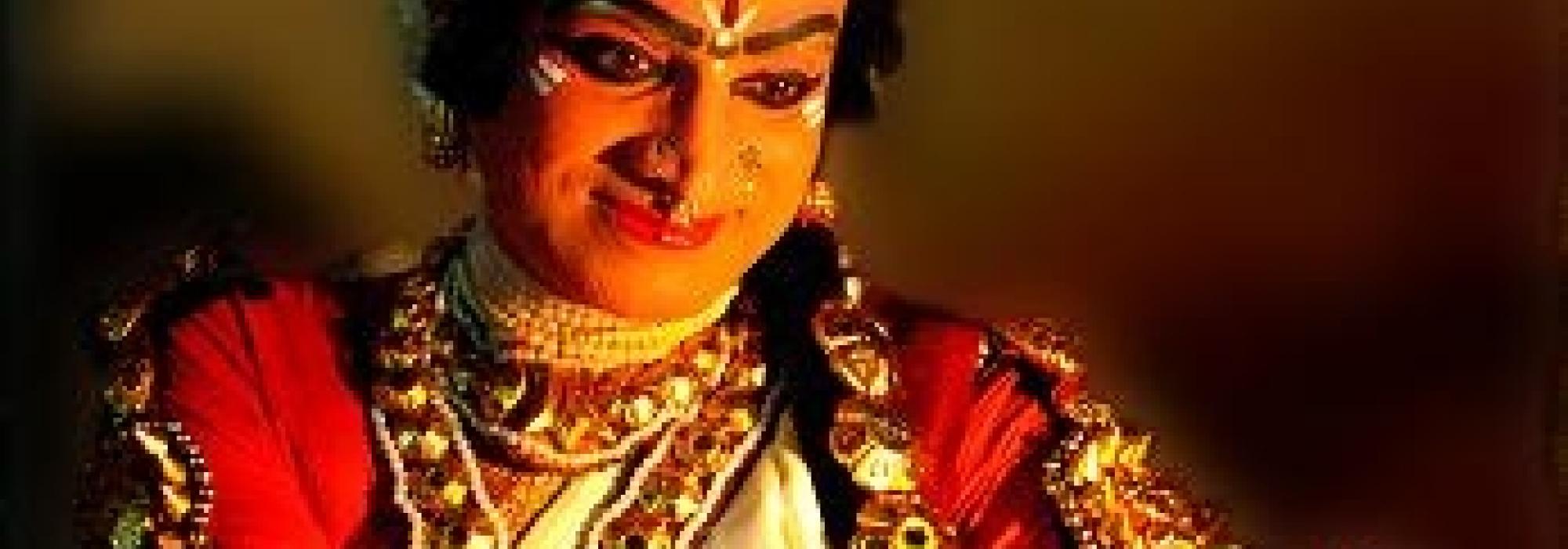

The senior Yakṣagāna Guru Kodadakuli Ramachandra Hegade played the role of Arjuna in Vijaya-vilāsa and did a great job in bringing out the nuances of his character. Bharatanṛtya Guru Sundari Santhanam played the role of Nala in Haṃsa-sandeśa and filled it with charm. She learnt Yakṣagāna with the sole purpose of performing in this prasaṅga, wore a kedagè mundalè and has even performed for tèrè-òḍḍolaga. It is interesting to note that a male artiste has performed a strī-veṣa and a female artiste has performed a puruṣa-veṣa in this production! Connoisseurs have greatly appreciated Sundari Santhanam’s attempt at playing a role in Yakṣagāna – they have hailed her nartana and abhinaya as a role model for all puruṣa-veṣas.

Summary

The Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna was conceived for a specific purpose and later grew to be a Yugala-yakṣagāna as well. Our vision was to extend the beauty of Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna to the entire Yakṣagāna theatre. However, due to several other commitments and also because of my own limitations, I have restricted myself to Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna. We would like to work on a complete Yakṣagāna production if interested artistes come forward and join hands with us. That way we can bring out an entire bahvāhārya production with rich caturvidhābhinaya. With this bigger intention of mine in mind, a few artistes came together to perform Līlātolana (the episode of Śrīkṛṣṇa-tulābhāra), a composition penned by me. Mantap Prabhakar Upadhya, Kodadakuli, Kolagi, Chapparamane, Halladi and Mururu Vishnu Bhat were among the prominent artistes who took part in the presentation. We staged it a couple of times. It however did not see the success that I had imagined and did not give me much satisfaction. There were several constraints that came in the way of success. We could not put into practice the vision of holistic aesthetics we had got. Moreover, we were unable to bring in all different kinds of characters, such as baṇṇda-veṣa, muṇḍāsu-veṣa and kirāta-veṣa that Yakṣagāna usually has.

I plan to take up a couple of more wholesome and profound productions in the future. We will need the assistance of interested artistes and organizers for this to take shape. However, given the number of resources needed for staging a full-fledged production, my ideas might not take shape at all. That is not something that bothers me too much, either. Artistes and connoisseurs who have witnessed our Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna productions and have understood and appreciated the concept may put efforts in applying the same set of aesthetics to a full-fledged Yakṣagāna production. Anyone who takes this up will need to keep Rasa as the ultimate goal. Rasa is copyright-free, after all!

Ekavyakti-tālamaddalè, Yakṣagāna with limited characters, presentations with hāsya-rasa, presentation of a select few sequences of Yakṣagāna and several other kinds of concerts that have been shaped since our presentation of Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna. Our presentations might have directly or indirectly inspired these newer ones. In case our presentations have motivated artistes to try out such novel ideas, it is certainly a good sign.

~

Dr. Padma Subrahmanyam once witnessed the Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna presentation of Mantap Prabhakar Upadhya. She greatly appreciated the show but expressed her view that the same kind of finesse and refinement needs to be brought into the mainstream Yakṣagāna too. She was happy to hear that I had a similar goal as well. We should never forget the value of the full-fledged Yakṣagāna-nāṭya even while trying out newer things. We will need to try to bring out more Rasa through Yakṣagāna. Some artistes have derived inspiration from our Ekavyakti productions and have implemented some of its elements in their performances. However, the elements they have taken in are largely limited to āhārya and other external aspects. Not much change seems to have taken place in sāttvika, āṅgika and himmeḻa. This does not brother us either. We will keep presenting our concept and ideas whenever we get a chance. Mā phaleṣu kadācana – ‘Do not worry about the fruits’ has been our working principle.

Comments and Criticism

Finally, let me provide an overview of the feedback and reviews our productions received. In the beginning, though people had a lot of curiosity about our attempts, there was quite an amount of opposition. Though there was quite a lot of appreciation, it largely came from objective and honest rasikas – they were the ones who could go beyond their personal preferences and make a balanced estimate of the pros and cons of these novel attempts. Those with a conservative mindset certainly did not give any positive feedback. At the end of our performances, we even handed out postcards with stamps stuck to them so that the audience could send us written feedback without spending their own money. There were people who hailed our presentations as ‘victorious’ and there were an equal number who wanted to bid a permanent farewell to our attempts. There was hardly any constructive feedback in the letters of appreciation we received. Similarly, there was no objectivity in the criticism that we received. People who hadn’t even watched our presentations wrote disparaging letters to newspapers. In the early days, I wrote rebuttals to all the accusations levelled against us. I ensured that my points were based on sound reasoning and also supported by śāstra and experience. There were several debates that took place face to face. Over time, however, we developed a dedicated audience with a matured heart for art appreciation. There were also organizers who had taste for good art. Though there were only a limited number of magazines and newspapers that reported our programs and published reviews, the number sufficed for our purposes. The encouragement and support provided by organizers and connoisseurs gave us a great deal of confidence and motivated us to improve our performances in all possible dimensions. We stopped all debates and arguments thereafter and focused all our time and energy on creative productions. This was a great learning for us – there is no point in responding to the accusations made by people driven by their own egos, ignorance and biases. We decided that only Time would answer them. An artiste need not respond to all the criticism about his art. We should confess that this was a much-needed change of attitude that we underwent.

When we started our series of performances titled Manèyaṅgaladalli Yakṣa-nāṭya, there were people who said that it was a sign of failure (suggesting that we were going door to door searching for audience). Such people even said that this was a conspiracy we had laid out. Yet, it has always been my view that sanātana-samskṛti must be preserved at the grassroots. Every nook and corner of the land needs to be penetrated for creating awareness about our rich art and culture. Thus, we found it important to make village dwellers understand and appreciate our Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna. Only this could strengthen the roots of our culture. We paid no heed to those who criticised our attempts. Our door-to-door performances had so much of impact that, what was merely an art, transformed into an ārādhana; in other words, it turned into a cākṣuṣa-yāga (a visual yāga). Many of our hosts even felt that they were performing a divine deed by organizing our performances and were elevated by the sublime experience they got in return.

By its very nature Ekavyakti-yakṣagāna is not meant for large audiences and big concert halls. A few learned and informal connoisseurs who can understand the nuances of the art will suffice. In addition, the audience should be seated close to the artiste such that they can notice all the intricacies of abhinaya and the artiste will also get motivated by the feedback that he constantly receives from the audience. We preferred to have chamber concerts. As artistes and audiences were both convinced about the philosophy of our presentations, they had no difficulty in organizing or enjoying them. We also understood by our experience that only a limited people would enjoy our art and it would also be impactful only on such people. While it is true that quantity and numbers matter to some extent for the promotion of an art, we realised the ephemeral nature of such parameters. Moreover, in our door-to-door concerts, our hosts also understood the lives of artistes, the manner in which they work in groups, the joys and difficulties of organizing a concert, and the relationship between the art and its artiste. They also realised the kind of personal and impersonal relationship that can exist between an artiste and a connoisseur. I have found these to be extremely important for our art. My anxiety of losing our traditional arts in the storm of globalization was also gone.

Our presentations initially did not have spoken word. All aspects of āṅgika, vācika, and āhārya were different and highly refined. In addition, there was only one veṣa throughout the performance. Because of these factors, many declared that ours was not a Yakṣagāna presentation at all. There were many who said that our presentations were obscene. Of course, there were a few who supported the idea that ours was indeed within the Yakṣagāna genre. They argued that just as Tāla-maddalè, which has nothing but vācika, is considered a form of Yakṣagāna, our concerts could be considered Yakṣagāna as well. There were a few immature people who couldn’t comprehend the difference between śṛṅgāra-rasa and rati-bhāva and decried our presentations as erotic shows. They were given suitable replies too by other matured connoisseurs. There are many who lost themselves to the sāttvikābhinaya and did not feel the need for the presence of any other character at all. Some others said that the ‘high’ Sanskrit culture has hijacked the ‘folk’ culture of Yakṣagāna. It is almost impossible for people with such biases to realise Ānanda, that is eternally fresh, original and beyond all highs and lows. Some people cared little for any kind of debate or conversation and preferred to take Ānanda as the best outcome of our presentations.

To conclude, I can confidently say that we have aesthetic reasons supported by śāstra, objective reasoning, and our experience to justify the manner in which we shaped our presentations. More than that, the very art exists, which can enrich open-minded connoisseurs with Rasānanda. Therefore, we have nothing to worry about. We are only grateful to all that we have received.

prekṣaṇīyakadānaṃ tu sarvadāneṣu śasyate - Nāṭyaśāstra 36.28

An audio-visual offering is the best form of dāna!

Concluded

This series of articles are authored by Shatavadhani Dr. R Ganesh and have been rendered into English with additional material and footnotes by Arjun Bharadwaj. The article first appeared in the anthology Prekṣaṇīyaṃ, published by the Prekshaa Pratishtana in Feburary 2020.