Dakshinamurti Shastri hailed from Kollegal. He was a vaidika[1] from birth; a person who was absorbed in the study of the Vedas. He was also one who deeply engaged in the study of Sanskrit poetry. Therefore when he uttered a Sanskrit word (or phrase), the pronunciation of the letters and the division of the words would manifest itself clearly.

He was a short man with a nice ivory skin colour. He was also well-versed in Tamil and Telugu.

It appears that musical knowledge ran in his family. I’ve heard his elder brother’s son Arunachala Shastri’s singing. It was the sort of music that adhered closely to tradition.

Dakshinamurti Shastri earned his livelihood by taking music lessons in a dozen houses of gṛhastas[2]. One of his disciples, M Venkappaiah was a relative of mine.

Shastri was particularly fond of singing difficult kīrtanas[3]. He would typically select the compositions of Muthuswami Dikshitar[4]. One of his favourites was the kṛti in Ānandabhairavī rāga – ‘Tyāgarājayogavaibhavam—samāśrayāmi.’

Tyāgarājayogavaibhavam।

Agarājayogavaibhavam।

Rājayogavaibhavam।

Yogavaibhavam।

Vaibhavam।

Bhavam।

Vam॥

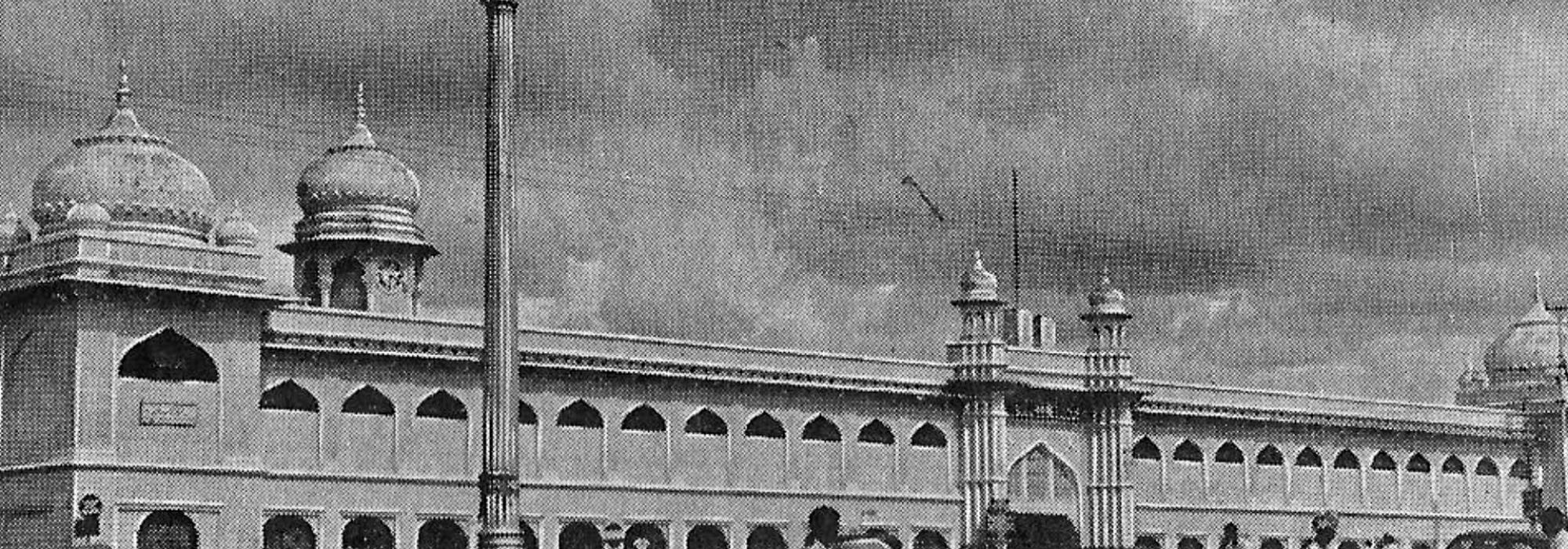

In the erstwhile Cāmarājendra Saṃskṛta Pāṭhaśālā, every year on Vināyaka Caturthī, it was customary to have Dakshinamurti Shastri’s concert in the evening. He would present a vocal music concert in one year and in the next, he would have a harikathā[5] exposition – if he felt happy, he would sing the then famous Kāmbhoji rāga varṇam of Vīṇā Kuppayyar:

Koniyāḍeda nāpai…

He would always sing this. In recent years I have not heard any musician of mettle sing this varṇam. Once I asked Shastri, “Why do you take up these difficult kṛtis—and that too, on the day of the Ganesha festival? The stomach will be full of kaḍubus, breathing is slow and heavy. Exposition in akāra[6] will be tiresome, isn’t it?” He laughed and said, “Are you suggesting that I sing ladies songs?”[7] His nature was somewhat strongly masculine – in the sense, it was that obstinate insistence to take up something complicated and manage it successfully.

Only great musicians with years of practice could impress Dakshinamurti Shastri with their singing. If Shastri sat in the audience, ordinary musicians would be terrified.

Arcot Srinivasacharya held Dakshinamurti Shastri in great regard. Not only that, whenever Srinivasacharya stayed in Bangalore, for three to four months a year, he organized a concert of Dakshinamurti Shastri once a week in his house and derive great joy from it.

Shastri was indeed a man of firm convictions but he was soft-spoken, courteous, humble, and friendly. Once there was a concert of Vīṇā Sheshanna; close to the end of the concert, Sheshanna looked at the audience and said, “If any of you have any specific requests, I will play whatever I can.” One of the members of the audience, a youngster, said in a soft voice, “I request for Nāyakī.” Dakshinamurti Shastri said in a loud voice, “Who doesn’t want Sheshanna’s Nāyakī?”[8] Everyone was amused. Sheshanna gladly played the Nāyakī rāga.

In his conduct, Dakshinamurti Shastri was pure, orthodox; he was a strict ritualist. Every day he would do the rudrābhiṣeka[9]. Every Monday he would do ekādaśavāra rudrābhiṣeka.[10] In his practices and dealings, he was a traditionalist. Poverty didn’t make him weak or helpless.

One of the great pillars of support to Dakshinamurti Shastri was K T Appanna, the owner of the Modern Hindu Hotel. Both of them were from Kollegal. Although they belong to different brāhmaṇa sub-communities, they belonged to the same family. The help and assistance that Appanna gave Shastri was enormous. Appanna was an extremely generous man, full of devotion towards the Supreme. He would find out, of his own accord, all the needs of Shastri and would ensure that Shastri was inconvenienced in no manner whatsoever.

Shastri had a humorous vein. One day he went to a friend’s shop in Chickpet holding a bunch of betel leaves in his hand. That friend said, “What’s this, Shastri sir, of all things you’re carrying withered betel leaves!”

Shastri said, “Not all of them are aged leaves. Some are young leaves, those are for me. There are a few leaves that are a bit older, those will be chewed by my daughter. And the rest will be chewed by that old lady at home!”

The friend teased him saying, “Shall I tell this at your house?”

Shastri said, “By all means, what’s the big deal in that! A fitting reply will be given. At any rate, I’m a vaidika. It’s been long since ṛṣipañcami!”[11]

This is the twelfth essay in D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 2) – Kalopasakaru. Thanks to Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh for his review.

Footnotes

[1] Traditional scholar well-versed in the Vedas; typically someone who led a simple lifestyle focusing most of his time and energy towards ritualistic and spiritual pursuits.

[2] Householders; gṛhastāśrama is the second life-stage (of the four) that corresponds to family life.

[3] A kīrtana or kṛti is one of the musical forms of Carnatic music. It is a song that is typically divided into three sections.

[4] Muthuswami Dikshitar (1775–1835) was one of the great composers of Carnatic music; along with Tyagaraja and Shyama Shastri, he forms part of the musical trinity in South Indian classical music.

[5] Harikathā is a form of traditional storytelling where the artist expounds a spiritual theme from the Indian Epics or the Purāṇas or the life of a great sage; the artiste (i.e. the harikathā vidvān) uses both songs and speech (and sometimes dance) as part of his performance.

[6] Refers to singing the melody using just ‘aah’ – often used in the rāga ālāpana (free-style improvisation of the melodic idea).

[7] This should not be taken as a sexist statement; while there might be a subtle mocking tone, he is basically conforming to the norms of the era that he lived in.

[8] This is a pun on ‘nāyakī,’ which is the name of the rāga and also a word that means ‘heroine.’

[9] Worship of Śiva in the form of Rudra.

[10] The same ritual repeated eleven times.

[11] The ṛṣipañcami is a festival during which the sapta-ṛṣis (seven great seers) are remembered with gratitude; while it was initially meant for men from all backgrounds, it is mostly practised by women. Shastri was perhaps suggesting that it’s a long time since ṛṣipañcami and so he can hardly expect special treatment from his wife.