Read the first part of this series

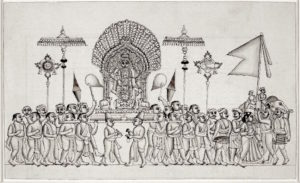

The scope, scale and expanse of enjoyment of both worldly life and that of the realm of emotions can be seen in the fabled descriptions, for example, by foreign travelers to Vijayanagara. Apart from the familiar descriptions of the bazaars of Hampi which sold precious stones and metals by the heap, we can turn to some enriching details about how they constructed their houses to begin with.

Epicurean Homes

Even if we ignore the gem-studded walls and diamond-encrusted pillars of the houses of the period, we still have an impressive picture of constructions built to suit all seasons. A perron each at the entrance of the house; carvings on pillars; paintings on walls; storeys at great height and openings therein to enjoy the cool moonlight[i] ; shrines, and multi-hued flags atop the house; a large flower garden with a pond full of red lotuses; those who could afford it also had an artificial hillock built next to it complete with small caverns bored into it and steps built to reach its summit; fountains. Given how severe summers were in Vijayanagara, there were separate air-conditioned rooms cooled by water continually splashing on the outer walls. Parrots, swans, peacocks, pigeons, deer, all formed part of the family. As a pastime, womenfolk of the house taught parrots how to speak, and coached peacocks in playing sports.

But of the most astonishing of all was the construction of the “Anger Chamber.” Any family member who was angry—specifically, if the woman of the house was angry with her man, she’d lock herself up in that room till her anger subsided. There’s no historical record to trace the name of the genius in whom originated this brainwave. But this is a truly great custom: thanks to this, the rest of the family could carry on their regular work unimpeded by such temper tantrums. Those who wished to calm down the angry person would anyway do visit the room and do the needful. Perhaps this was originally Dasharatha’s brainwave to mollify a periodically-upset Kaikeyi. Krishnadevaraya and Peddanna had no need for it but Timmanna was forced to build it for the sake of Satyabhama[ii].

The Bathing Ritual

Taking a bath formed a key pre-dressing element of the people of Krishnadevaraya’s period. When we examine some details of the method and procedure of bathing, it’ll be clear why it was regarded so highly.

Very simply, bathing meant “Abhyanga” or inunction[iii]. It appears that inunction was part of their everyday bathing ritual. Indeed, daily oil massage is consonant with the prescriptions of Ayurveda. A devout Vaishnava named Vishnu Chitta had organized in his house Abhyanga for Vaishnava devotees visiting from different lands. These devotees would be given the Abhyanga oil served in a bowl made from the shell of banana flowers. The actual bath was had in the river. But Vishnu Chitta was a poor man and thus could afford only this luxury.

But the standard of the Abhyanga of the wealthy was truly a class apart. First, fragrant oils like that derived from the Champaka (or Champa) flower would be massaged on the head. Then someone would gently part the strands of the hair with their fingernails to ease away any tangles. This process also included patting the head by sprinkling rosewater and then applying a paste made of sandalwood and gooseberry. And further, “even as the flood of the rosewater mixed with the scent of the Javvaji from the Goa country spread their surfeit of fragrance,” hot water would be poured on the head in a never ending stream. After the closure of this process, someone would wipe the water off the body with a fine, soft cloth meant for the purpose.

Ayurveda falls short of words to extol the benefits of Abhyanga. But it’s clear that these enormous benefits form one of the reasons our elders prescribed Abhyanga as an essential part of all auspicious occasions like festivals, weddings, and so on.

And so, the connoisseurs of Krishnadevaraya’s period who also appreciated the lasting value of good health, heightened their epicurean experience by adding fragrant oils to their Abhyanga routine. Besides, both women and men sported long, thick tresses, a physical attribute highly prized as an ornamental value. We haven’t still[iv] completely forgotten the fact that a woman endowed with long and luxuriant hair is a thing of beauty and a joy forever. But the perception that long hair on men is not decorative but rather looks perverse has gained strong currency of late. And, the Crop—that singular labarum of cultural slavery to Western colonialism, has implanted itself upon the heads of our men everywhere, thus bolstering this perception. And not only just our men. Our women too, have fallen prey to this curiosity and have succumbed to chopping off their hair.

We can count Peddanna as the foremost among those who genuinely appreciated the beauty and a sense of striking personality that men endowed with bounteous tresses possess. He ignores the fact that Bhagiratha—grandson of Emperor Sagara—who undertook harsh penance[v] for a thousand years had become completely frail but laments the fact that his “long and brimming hair” had become horribly matted.

And Abhyanga was the main aid to the growth of long and thick hair. Which is why it was highly prized among the people of Krishnadevaraya’s days.

Dress, Jewelry, and Personal Adornment

We can turn to their dressing now. Typically, people of that era wore colourful clothes. Although men wore all-white on rare occasions, women found no use for that colour. Indeed, when Satyabhama sulked, she did it by wearing all-white! At all other times, she wore, with great pride, clothes coloured with a reddish or saffron tint. She was especially fond of clothes that were adorned by a gold border.

Yet others wore clothes made of “three colours.” These clothes were apparently made of material that was as delicate as the scales of a snake, and which would “fly away when blown by the force of the wind emitted by one’s mouth.” Indeed, there was great demand for such gossamer clothing, which is why it was possible to manufacture such subtle yarns.

Today’s Khadi-wearing warriors think that thicker the Khadi they wear stronger is their display of patriotism and closer they inch towards swarajya or freedom. This is why despite constant and prolonged effort, it is still difficult to find fine and delicate Khadi clothes. But we digress.

In the matter of jewelry, it appears that there was little or no difference in what men and women wore. Although there might’ve been differences in type, shape, form, and application, both men and women were equal in their desire for wearing jewelry.

Our Shastras prescribe the wearing of jewelry to women. But Krishnadevaraya’s state policy prescribed that even men be decked in jewelry from head to toe! Necklaces, shoulder-braces, finger-rings, jewel-bedecked belts, bangles on wrists and ankles…these were worn both by women and men in his time. The differences seem to be in the crown or jeweled headgear worn by men, and noserings worn by women respectively. Thus, it appears that a husband and wife, united in equal desire for jewelry, results in peace in a marriage. Either both could afford and wore jewelry, or they had no jewelry at all. This additionally eliminated the tension resulting from a feeling that the husband would work hard to earn all these riches while the wife simply spent it away on her adornments.

But when we think about it deeply, it’s strange why men’s interest in wearing jewelry and decking up has dwindled. We can’t claim that this ornamental interest has been completely destroyed in the present time but it’s true that the condition is really pitiable among today’s men. The interest among the men in Krishnadevaraya’s era for wearing jewel-studded crowns, necklaces and so on has vanished and has given way to buttons, watch-chains, and finger rings: in rare cases. The spread of this interest also appears to be tinged with fear and cringing. The essence of this new phenomenon is clear: we no longer have the courage to wear ornaments bequeathed to us by our own culture and tradition, to savour them for our own joy but have become mentally and culturally enslaved such that we wear alien trinkets to appease foreigners.

And what applies to ornaments applies to dress. We cower to dress up in an exquisite Salem dhoti—spun with a fine yarn, delicate like a flower—but show no shame in showing up wearing a Surge Suit. We are ashamed to drape ourselves in an elegant Kacche[vi] and dag around confidently in public. But we strut around proudly like walking sticks in suit, uncomfortable and afraid of spoiling the crease.

Our ancients were free men and women; they were true connoisseurs. They fearlessly displayed their love for jewelry by wearing it unabashedly; they decked up for their own joy. Not for them today’s sorry task of putting on a sheepish grin to appease others.

To be continued

Notes

[i]Technically known as a Chandrashaale

[ii] An allusion to an episode in Timmanna’s poem “Paarijataapaharanamu” where he recounts the quarrel between Sri Krishna and his wife, Satyabhama.

[iii] Known as “Abhyanga” or oil massage.

[iv] This essay was written more than sixty years ago.

[v] The fabled tale of Bhagiratha, an ancestor of Rama, undertook a 1000-year long penance to bring down river Ganga from the heavens so that her waters could expiate the sins of his deceased ancestors.

[vi] A dhoti wrapped around the legs in a fashion that forms a neat partition between the legs, almost like a trouser.