Chinmaya Vishwavidyapeeth and Chinmaya International Foundation have jointly organized a ten-day Summer School from 17 to 26 June, 2017 to realize the spirit of Indian culture through the creations of Vyāsa, Vālmīki, Kālidāsa (and Guṇāḍhya) at the Adi Sankara Nilayam, Veliyanad. The Summer School is support by Indian Council of Philosophical Research. Prekshaa is delighted to present a daily summary of the discussions over the course of the next ten days.

Day 1, Session 1: Inauguration

After a melodious invocation by Swapnil Chaphekar (Faculty, Chinmaya Nada Bindu Gurukula), N M Sundar (Trustee, Chinmaya International Foundation and Campus Director, Chinmaya Vishwavidyapeeth) welcomed all the participants—young and old—to the birthplace of Adi Shankara. The Chinmaya International Foundation was established as the research wing of the Chinmaya Mission. He mentioned that Summer School 2017 was a tribute to the masters of our ancient civilization.

After the lighting of the lamp by the dignitaries, Naresh Keerthi (Faculty, Chinmaya Eswar Gurukula) introduced Prof. B Mahadevan (Vice Chancellor, Chinmaya Vishwavidyapeeth). The vice chancellor praised the wonderful choice of title for the summer schools. “This is a wonderful combination of three great personalities. When we talk about a work, we basically talk about the personality of the creator of the work,” he said. While it is quite a task to cover such an expansive topic in a short period of ten days, he expressed immense confidence that Dr. Ganesh would not only introduce these great masters to the participants but also inspire them to go back and read these works deeper. Prof. Mahadevan said that culture is important for society, and more ancient the culture, the more valuable it is. Culture must be preserved at all costs because without culture, society will lose its identity. He concluded by saying that the situation is filled with hope, for it is no joke for close to sixty people to turn up for a ten-day-long workshop such as this one.

Prof. K T Madhavan (Chair of International Studies at Kerala Sanskrit Academy, Thrissur) gave the inaugural address. He began by invoking the famous verse of Vyāsa "श्लोकार्धेन प्रवक्ष्यामि यदुक्तं ग्रन्थ कोटिभिः / परोपकारः पुण्याय पापाय परपीडनम् " (I will tell you in half a verse what has been said in a million books: helping others is good, harming others is bad.) He mentioned that these great poets—Vyāsa, Vālmīki, Kālidāsa—are the representatives of the culture of Bharātavarṣa. He said, “While the three of them have several agreements in technique, plot development, character portrayal, description of nature, and their connection with culture, they have their own individuality and it would be unfair to compare the three.” When the culture is disturbed, the country is destroyed; it is the culture of Bhārata that connects people from different backgrounds in India, like the thread that holds together flowers of various colours in a garland. This is the reason why our enemies have always tried to attack our culture. Prof. Madhavan stressed on the point that the preservation of culture depends on our womenfolk and that they must be empowered.

Prof. Sreekala Nair (Dean, Faculty of Social Sciences, Head of the Department of Philosophy, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, and Member of Indian Council of Philosophical Research) began by saying that Vyāsa, Vālmīki, and Kālidāsa are luminaries in the galaxy of world literature, and not just of Sanskrit literature. Their works have been inspirations for generations, not just to writers and poets but to all artists. She mentioned that any country or society that wants to develop should nourish and promote its culture. Self identity is essential for a society; if we don’t know ‘who we are’ that is a sad day for any society. In India, philosophy and literature are interconnected. Sanskrit language is the foundation of our culture. It is inseparable from Indian culture and ethos. She concluded by recalling the words of Tagore, who said that the Indian intellect lives in a joint family and not a nuclear family, implying that the various disciplines in India have always been interconnected, not discrete.

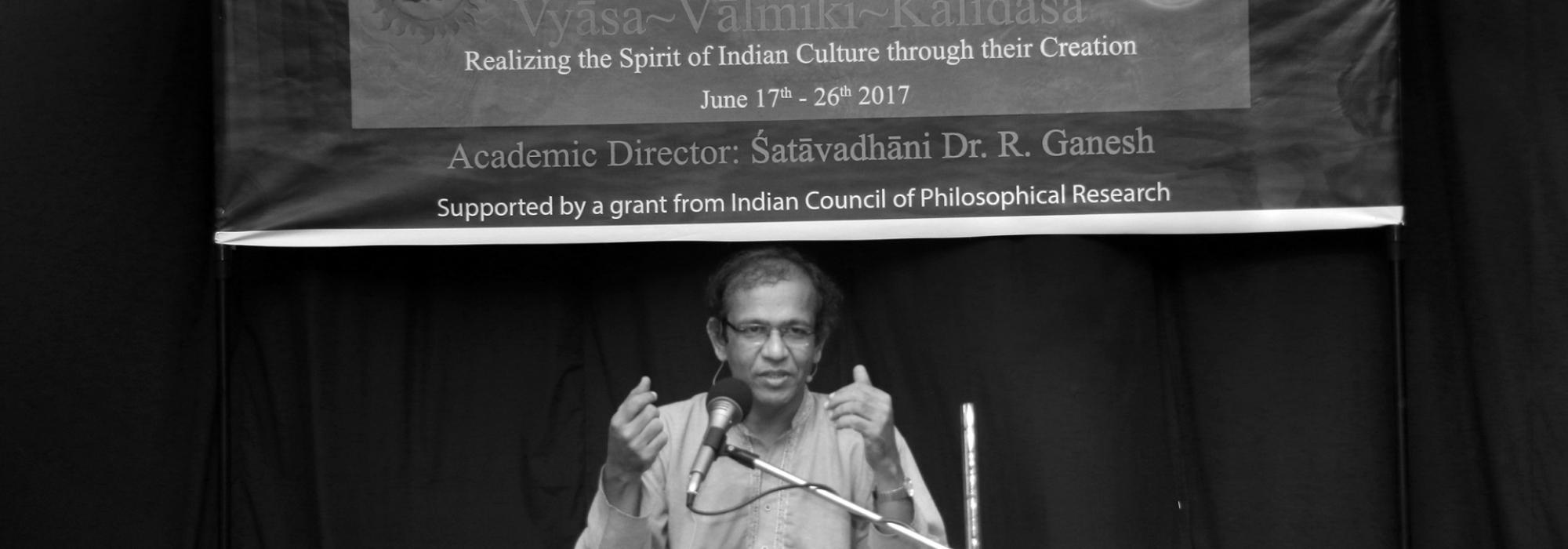

Naresh Keerthi then introduced Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh (Academic Director, Summer School 2017) in glowing words. In his short speech, Dr. Ganesh said, rather humorously, that poets were like master thieves – they steal from so many places, from so many sources, and are a veritable treasure house. They are perennial sources for joy. And a rasika who finds joy in poetry has pleasure without the pressure. He narrated the famous exchange between the seer Bhṛgu and his father Varuṇa from the Taittirīya Upaniṣad, emphasizing on how the quest for the son stopped once he attained ānanda.

The DVD set of Kalayoga (Summer School 2016) was released by Swami Sharadanandaji (Senior Acharya, Chinmaya International Foundation and Member of the Management Board, Chinmaya Vishwavidyapeeth).

Swami Sharadananda briefly spoke about the importance of dharma and how the puruṣārthas are present in the works of Vyāsa, Vālmīki, and Kālidāsa. He said that the Itihāsa and Purāṇas were able to capture the essence of the Vedas in simple language. He requested all the participants not only to enjoy and learn through the Summer School but to go forward and become representatives of dharma and our great culture.

Day 1, Session 2: Introduction to the Summer School

Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh

After all the participants introduced themselves, Dr. Ganesh gave a quick introduction to the Summer School. He said that it is always better to read Indian language translations of these Sanskrit classics rather than depend on English translations. There is a cultural context to several words of Sanskrit that are easily accessible in the regional languages of India but are impossible to capture in English. He gave the example of the word agni, which in English is just fire, but has a deep cultural connection in India. It is fire alright but much more than fire. He emphatically said, “English has not become the cultural lingua franca of India and it will never be able to. Sanskrit was the cultural lingua franca and continues to be so, through the various regional languages.” He went on to explain the uniqueness of the Indian tradition. Some civilizations and cultures in the past had the epic tradition, like the Greeks and Romans. Some of these ancient epics include Beowulf, Iliad, Odyssey, Aeneid, and Gilgamesh. These did not, however, have a Holy Scripture or gospel. Some cultures had holy texts, like Judaism, Christianity, and Islam but didn’t have epics. Some like the Chinese, Japanese, Inca, and Maya civilizations had neither epics nor gospels. It is only in India where we have sacred works like the Vedas and the epics like Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata. The greatest beauty, however, is that we have the tradition of adhering to a text and then transcending it. While adhering to a work is a necessity, transcending it is essential. While the Vedic literature was deva-kendrita (centered around deities), the epics are jīva-kendrita (centered around humans), and the works of Kālidāsa are bhāva-kendrita (centered around emotions). In the Vedas, the deities help humans as they are; in the epics, deities incarnate as humans; and in later poetry, the focus is on human emotions. Dr. Ganesh mentioned how this theme is beautifully brought out in D V Gundappa’s Antaḥpuragītā. And when we explore jīva and bhāva, even the devas will be there to worship it.

Day 1, Session 3: Life Principles from the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa

Prof. B Mahadevan

Prof. Mahadevan started his talk by giving three reasons for reading the Itihāsa and Purāṇa literature. First, they help clarify the ideas of the Vedas in simple language. Second, the epics give us two separate approaches – what is the ideal way and what happens in reality. If Rāmāyaṇa shows us the ideal path to living, Mahābhārata gives a view of what happens when people try to follow that path and fail or succeed. Third, in the original works, Vyāsa and Vālmīki never lose an opportunity to share a fundamental principle of living. Prof. Mahadevan went on to analyze the character of Rāvaṇa using what he called a universal framework of destruction in six stages:

Stage 1. The character develops enormous strength. However, striving for greatness and achieving it naturally leads to ego. Although Rāvaṇa measured in greatness with Rāma, he did not measure in goodness.

Stage 2. The character indulges in adharmic acts. The heightened ego removes fear of dharma and he loses control of his senses. He doesn’t allow for dissent of any kind.

Stage 3. The character invites the wrath of people and is cursed. The wicked person digs his own grave. It is the beginning of his end.

Stage 4. The destruction begins. The character doesn’t listen to wise counsel from any source.

Stage 5. The destruction is imminent as the character is blinded from reality. Upon realizing the situation, the character becomes desperate and resorts to foul play.

Stage 6. Aftermath is colossal. When a leader commits a mistake, there is destruction not just of the self but also of family. It is too late even to repent.

Day 1, Session 4: The Philosophy of the Epic Tradition

Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh

Dr. Ganesh gave an overview of the workshop by laying out the philosophy of the epic tradition. He mentioned that the great poets of the past had a fantastic communication skill. As long as human nature remains, these poets will have relevance. As long as humans are emotional beings, these epics will be read. There is something in them for everyone.

Dr. Ganesh emphasized that the purpose of art is ānanda (enjoyment) and attempting to extract a social message from a work of art is to destroy it. The epics help us sublimate our existence. It is when we transcend the threshold of ignorance that we have awareness. Our epics naturally help us to know ourselves.

He explained the difference between kāvya and śāstra using an example from dance. In the classical dance tradition of India, we have mudras and hastas. Mudras are used to insulate oneself from the world while hastas are used to communicate something to the world. Śāstra is focussed and instructional while kāvya is communicative and entertaining. If kāvya can be likened to a fresh fruit, śāstra is like a capsule with the vitamin present in the fruit.

We all accept our existence without any questions; it is self-evident. So also, our emotions are self evident. We don’t need anyone else to tell us whether we are happy or sad. Existence (sat), awareness (cit), and bliss (ānanda) are self-evident. No external proof is needed. Bliss is therefore our natural state. Any deviation from bliss is unnatural.

All of us have desires (kāma) and find the means (artha) to fulfil them. The desires and the means to their fulfilment must be managed by the sustainability principle (dharma). Dharma is both an enforcement and a realization; the former is implemented by the law while the latter is evolved through culture. This culture teaches us to look at everyone as extensions of ourselves. When this culture becomes a part of our nature, then dharma graduates to mokṣa, the state of lasting bliss. The path tread by the sādhaka of Vedānta with mindfulness becomes the way of living of the siddha, who is perfected in Vedānta.

An observant person realizes the greater cosmic order in the universe, what our ancient seers called ṛta. Having realized this order and the interconnectedness of everything, he naturally develops a gratitude for his existence and what he is receiving from the universe. This feeling of ṛṇa, cosmic indebtedness, inspires one to tread the way of dharma, which helps sustain the grand order behind the universe. How to follow the path of dharma? This is given in the beautiful pedagogy of yajña (sharing and offering), dāna (philanthropy, giving) and tapas (effort, penance). This results in Goodness in thought, Truth in speech, and Beauty in action.

Both Vyāsa and Vālmīki are great poets but when we compare them, we find that the Mahābhārata is more profound when compared to the Rāmāyaṇa both in form and content. While the strength of Vyāsa is divergence, Vālmīki’s strength is convergence. While Mahābhārata’s storyline is long and winding, Rāmāyaṇa’s storyline is a short, straight line. While Vyāsa and Vālmīki have different approaches, their purposes are the same.

Dr. Ganesh concluded with a poignant observation about Vyāsa, who was such an open-minded and unbiased writer. Typically, when we want to abuse another—in any language—we point fingers at the other’s birth; in other words, we abuse his mother. When this is the case, Vyāsa openly shares the secret of his birth, which one could easily look down upon in contempt. Dr. Ganesh concluded by quoting a beautiful verse from the समयोचित-पद्य-मालिका –

कानीनस्य मुनेः स्वबान्धववधूवैधव्यविध्वंसिनो

नप्तारः किल गोलकस्य तनयाः कुण्डाः स्वयं पाण्डवाः |

तेऽमी पञ्च समानयोनिरतयस्तेषां गुणोत्कीर्तना-

दक्षय्यं सुकृतं भवेदविकलं धर्मस्य सूक्ष्मा गतिः ||

Vyāsa, the saint, was a kānīna (born to his mother while she was still unmarried). He fathered the children of his brothers’ widows and thus those children (Pāṇḍu and Dhṛtarāṣṭra) became golakas (born to widows through niyoga). The Pāṇḍavas, grandchildren of Vyāsa, were kuṇḍakas (born through other men while the father was still alive). They were married to a single woman, Draupadi, and thus had indulged in polyandry. Celebrating their lives would yield infinite virtue forever. The way of dharma is intriguing yet so sublime!

Comments