The paintings on epic and purāṇic themes by Sri Chandranath Acharya, an artiste par excellence, represent an optimal blend of the classical Indian flavour with the techniques of the West. He has not only mastered the traditional Indian techniques but also brings in perfect anatomy and three-dimensional charm, typical to the Greco-roman tradition and the Italian Renaissance. He has taken forward the tradition of master artistes such as Raja Ravi Varma, M V Durandhar, M T V Acharya, Vaddadi Papaiah, and S M Pandit. Through his immense creative potential, he has added fragrance to classical themes and by his mastery of form, he has expanded the possibilities of the challenging medium of water colours. The manner in which he brings in nuanced details rich with emotional content bears testimony to his peerless skill.

It is needless to say that the content of his Mahābhārata paintings is genuinely Indian with its roots in the original Sanskrit epic and Kannada retellings of the same. Most of them were painted to illustrate the episodes of Prof. A R Krishnasastri’s Vacana Bhārata (1950), which later appeared as a series in the Kannada weekly Sudhā. Prof. A R Krishnasastri was a doyen of Kannada and Sanskrit literature and his Vacana Bhārata has been widely held as a classic for being an honest and highly appealing retelling of the Mahābhārata in Kannada prose. Chandranath Acharya ably illustrated segments from the work, which ran into more than seventy episodes. Some other illustrations appeared as a part of the book Kumāravyāsa-bhārata-kathā-mitra (2010) authored by Prof. A R Mitra. The skill of the artiste’s brush elevates each illustration into an independent work of art. The artiste created each of these works of art in a short span of about three to six hours.

The remarkable feature of Chandranath Acharya’s Mahābhārata paintings is the realistic depiction of narrative episodes using rich colours, without compromising on sublimity. The artiste never fails in his proportions – be it vegetation, animals, or humans. Lines blend into colours and when they stand apart, they do so to create a specific effect on the viewer. Just as silence, when creatively used between svaras adds charm to music, the artiste uses white spaces of the paper meaningfully between the colours. Thus, colours contextualise and sanctify the whiteness of the paper. His representation of characters is true to the epic poet’s vision and agrees with the common Indian psyche. A unique feature of his paintings is the different ‘camera angles’, i.e., perspectives that he brings to well-known episodes. The paintings also depict a moment of an episode filled with action, thereby making the characters and the surroundings dynamic. Additional colours in the background add intensity to the governing emotion, i.e., the sthāyi-bhāva of the main characters. In many episodes, his characters are seen in their casual and informal postures as required by the context. A signature feature of Acharya’s paintings is the wild foliage in different colours. He employs them creatively to suit the context, character, and emotion. He brings in the poise and grace as required by the character, giving each a distinct and unique personality.

[The following link contains images of all the works of art discussed below - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bW4yjnW6ZNs ]

The painting that depicts Yayāti rescuing Devayānī shows us the characters from the eyes of a viewer who stands on the shore of the lake at a higher elevation. Devayānī’s hair is wet as she has taken a dip in the lake and she holds on to a creeper (of hope) as she ‘looks up’ to Yayāti. Another painting depicts Śakuntalā who is lost in deep love in the company of Duṣyanta. She has her eyes closed, enjoying her beloved’s touch. Their love is also suggested by a peacock couple in the background.

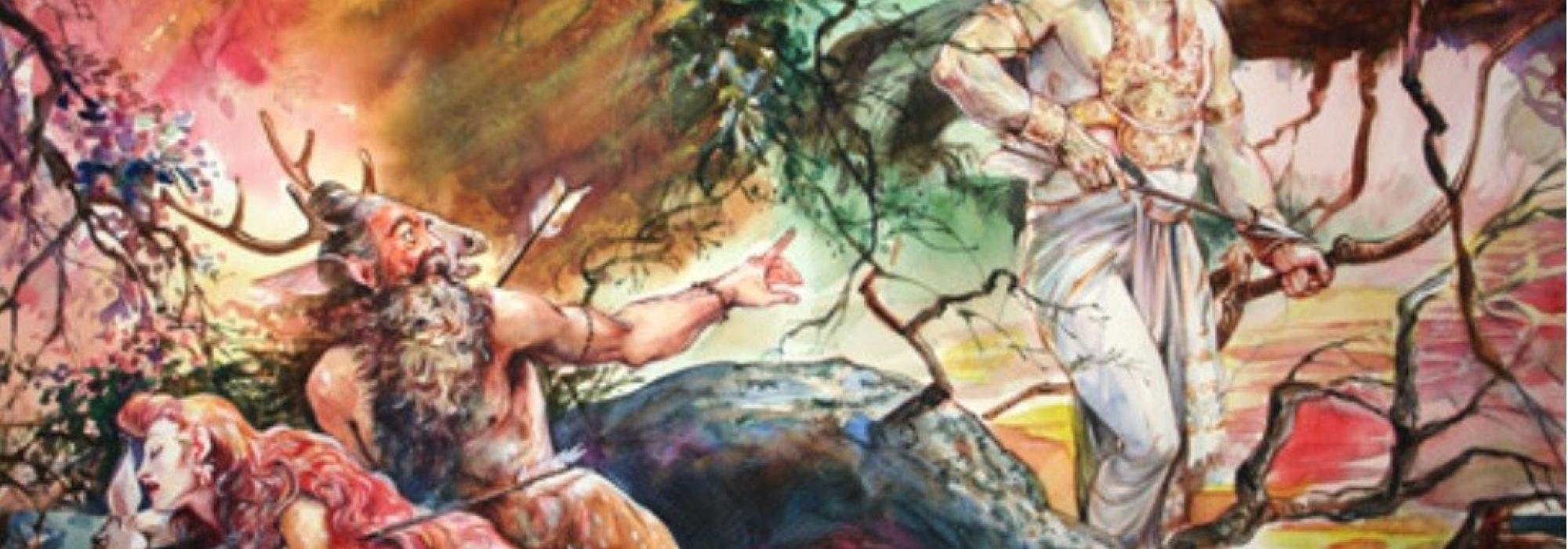

Pāṇḍu shooting arrows at the deer couple, who transform into humans is a masterpiece. The deer are subtly shown in their intimate position, while they slowly transform into humans. The artiste uses a common eye to suggest the eye of the deer and of the ṛṣi Kindama. His upper body is human which enables him to utter a curse. Pāṇḍu is perplexed and stands stupefied. (See the cover images). In another painting, Pāṇḍu, who is overcome by lust is seen hugging Mādrī who is decked in spring colours. Pāṇḍu's pale body and his eyes, which almost look lifeless, betray the impending calamity.

In yet another painting, Vasudeva is shown carrying a baby Kṛṣṇa sandwiched between a turbulent Yamunā and dark clouds which are pouring down. They are umbrellaed by the endless snake, Ananta. The radiance of the baby adds light to the picture and delight to Vasudeva’s face. In the painting where Droṇa confronts Drupada, the artiste creatively uses a pillar at the centre of the composition to show the demarcation between outside and inside the palace. The rākṣasa Hiḍimba is shown in his beastly form, with no clothing revealing the crudeness of his personality, while a masculine Bhīma with eyes red with anger subdues him. The fight between Arjuna and Indra in the episode of the khāṇḍava-dahana is depicted by the artiste as a clash of fire and water. The dynamism of the heroes, horses, and elephants are biologically accurate and create an immense impact on the viewer.

The Kauravas taunting the Pāṇḍavas is another painting with brilliant composition. The Pāṇḍavas and Draupadī have been thrown out of the palace, are devoid of ornaments and have been subject to living in the forest. The Kauravas laugh at their pain and mock them with different facial expressions and gestures. An enraged Bhīma lifts his mace, perhaps, pledging to pay back every insult. Arjuna appears to support Bhīma’s emotion, while Draupadī, with her hair untied, looks helpless. Yudhiṣṭhira is speechless and Vidura, who is on the side of the Pāṇḍavas, is a mute spectator of the injustice. The Kauravas stand at a higher pedestal inside the palace, while the Pāṇḍavas stand lower on the stairs, outside. In all the paintings where she appears, Draupadī is shown with attractive features and dark complexion, true to her name Kṛṣṇā.

Śrī-kṛṣṇa meeting the Pāṇḍavas to advise them about the rājasūya-yāga depicts each of the five brothers with different facial expressions. Yudhiṣṭhira, the king is decked well and so is Kṛṣṇa, a guest. The casual attire and informal postures of the other brothers betray the familiarity and intimacy they have with Kṛṣṇa. The body language of the characters in this particular painting like all other works of Chandranath Acharya show the particular anubhāva, the expression of emotion. Kṛṣṇa is shown speaking with his lips in motion and hands adding to the conversation. In yet another episode, the spinning of the sudarśana-cakra is suggested by colours going in circles around Śiśupāla’s head which is chopped off.

Duryodhana letting loose crocodile tears, filled with envy and anger comes about effectively in many paintings. The invisible yakṣa is brought to life through a foggy form surrounded by ethereal colours. A helpless and reluctant Sairandhrī stands at the doorway and Kīcaka with seductive looks waits on his bed. A wrathful Dhṛṣṭadyumna chopping off the head of a meditating Droṇa even as the life force goes away from the latter, depicted through a golden stream of light. The masculine gadhā-yuddha between Duryodhana and Bhīma evokes intense vīra and raudra rasas in the onlooker. A wounded Duryodhana is shown lying with his mace as his pillow, being attended by Kṛpa, Kṛtavarma, and Aśvatthāmā. A compassionate Sañjaya consoles the blind couple – Dhṛtarāṣṭra and Gāndhārī – even as he tells them about the death of their eldest son. Kṛṣṇa's passing away shows the hunter Jara aghast, while the divine face of the yogeśvara is undisturbed, peaceful and has a sublime charm.

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the Mahābhārata paintings of Chandranath Acharya have the potential to leave a lasting mark on the readers of the epic as the actual manner in which the incidents took place. Mere utterance of the names of devīs such as Sarasvatī and Lakṣmī brings to the minds of the Indians the images painted by Raja Ravi Varma. Just as his paintings have become synonymous with the names of the devīs, Acharya’s Mahābhārata paintings have the potential to become synonymous with the epic. It wouldn’t be a surprise if the later generations identify his Bhīma or Paraśurāma, Kṛṣṇa or Draupadī as the true representation of the personalities. Chandranath Acharya has given shape and colour to the verbal medium. He continues the artistic tradition of the greatest epic of the world in an impeccable manner. His paintings contain beauty which can make them immortal, just like the immortal epic.

[This article serves to introduce some of the paintings of Sri Chandranath Acharya that were on display in the Indian Institute of World Culture, Bangalore in June 2022. It is not meant as an exhaustive analysis of all his works. It serves to creatively appreciate some of the nuances in his works of art on the theme of Mahābhārata. More information including the biographical details about the artiste can be found here https://chandranathacharya.com/. The artiste holds the copyright for all images.

Thanks to Shatavadhani Dr. R Ganesh for his inputs in writing the article]