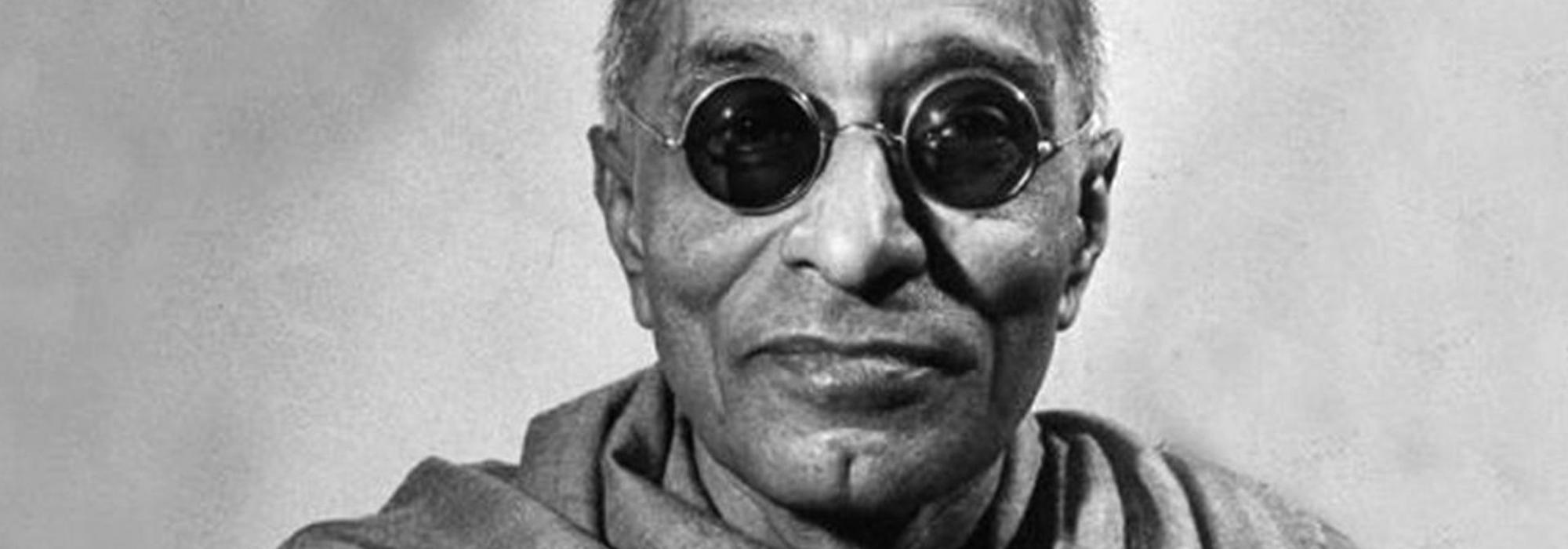

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari always wore smoked glasses (i.e. dark glasses). This gave way to ridicule. It’s true that his eyesight was weak, just like several others. But why the black-coloured glasses? So that others do not realize how his eye-balls are turning; the movement of the eyes indicates the intent of the mind. When the mind is under the grip of anger and distress, or is thinking of something insincere, it shows in the eyes; the wise may understand that; to avoid that, dark glasses to hide one’s real intent – such was the rumour. I can’t say whether this originated from friends or foes. But that erroneous notion had spread among the public. I can confidently say this was a misconception.

I’ve known Rajagopalachari for nearly fifty years. He was Navaratna Rama Rao[1]’s classmate and close friend. One could write a poem about that friendship! Let me illustrate.

Friendly Nature

The news of Navaratna Rama Rao’s demise [in 1960] reached Rajagopalachari by telegram. He was touring the Kerala region at that time. Soon as he heard about his friend’s demise, he cut short his tour and travelled to Bangalore by car. It was evening by then and the cremation was already over. After enquiring at his residence, he said, “It’s dark now. Can I have someone accompany me to the crematorium tomorrow morning and show me the spot?” Accordingly, the next morning at five, he came to Rama Rao’s house and accompanied Krishnaswami (Rama Rao’s younger brother) to the crematorium; there he did a pradakṣiṇa[2] around the pyre, paid his respects, and returned. He bought new clothes for Rama Rao’s daughter, telling her to wear those clothes on the day of the śubha-svīkāra[3]. A few months later, he played a big part in arranging the girl’s marriage.

Friendship Without Guile

Friendship without guile – such was Rajagopalachari’s friendship. This friendship started when Rama Rao and Rajaji were both students at Bangalore’s Central College. Both had a deep love for English literature. Both were devotees of Shakespeare. They were both competent in debates and arguments. Both were curious about matters pertaining to philosophy. More than anything else, they had mutual admiration. Can one fathom the cause of admiration? Apparently, after completing his education, Rama Rao too practiced law at Salem, as Rajaji’s colleague. The friendship that developed between them was a rare one. Rajaji himself alluded to this in one of his public speeches in Mysore. He said, “Times are becoming vicious now. Circumstances have changed. Everyone now looks out for himself and thinks one’s riches only as one’s own. These days, friendship is self-serving. There is no chance for friendship if there is no self-serving need. Friendship that looks not for reward is thus dejected. In my friendship with Rama Rao, neither he nor I had cause for selfish thoughts. It was friendship for friendship’s sake: genuine, mutual friendship and admiration.”

Strategic Intent[4]

I’m not saying, however, that Rajagopalachari lacked the intention to be strategic. There was no deception in him. There was strategy. Let me give you an example: A public meeting. The organisers ask for Rajaji’s suggestions beforehand. Rajaji names those who should speak that day. He plans the order in which those people should speak, who should speak after whom. Then he peers down through his glasses and identifies others who have come to the gathering. He would know who among them will be ready to speak. He calls such people to talk. These five or six people will also speak. After all of them finish, Rajaji gets up. He explains, in what he feels is an appropriate way, the points made by the speakers; not only nourishing the points, but also correcting their errors, and more importantly, if any of them had posed any questions, he would answer them all.

Thus, the last speech was Rajaji’s – where he corrected all the points. In this, there was no guile or insincerity. The idea was to ensure that the day’s proceedings went on smoothly, without any hiccups.

In the Mudrārākṣasa, a Sanskrit drama, there is a verse [about Cāṇakya] –

muhurlakṣyodbhedā muhuradhigamābhāvagahanā

muhuḥ sampūrṇāṅgī muhuratikṛśā kāryavaśataḥ।

muhurnaśyadbījā muhurapi bahuprāpitaphale-

tyaho citrākārā niyatiriva nītirnayavidaḥ॥

(Act 5, Verse 3)

Sometimes, it's clearly understood while at other times, it's too profound to grasp

At times, it's complete with all its parts while at other times, it's extremely subtle,

depending on the work to be accomplished

Now, the seed is destroyed and now, the fruits are aplenty

O how strange are the precepts and paths (of a statesman), just like Fate!

A minister, under some circumstances, has to roar like a lion; at other times, he has to sing like a lark; he has to gallop like a horse sometimes; slip away like a serpent at other times. In politics, there are several morals, methods, and paths. Those who object to Rajaji must bear this in mind. His is not just a scholarship of words. Achieving a higher goal is his aim. He plans his strategy to suit the time and circumstance. It’s difficult for a commoner to understand this. Apparently, there’s a saying in Arabic – “Only a king understands the intent of kings.”

Rajagopalachari was not only a goal-oriented thinker; he was also a strategist.

To be continued.

This is the first part of a three-part English translation of the fourth essay in D V Gundappa’s magnum-opus Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 6) – Halavaru Saarvajanikaru. Edited by Hari Ravikumar.

Footnotes

[1] 'Navaratna' Rama Rao (1877–1960) was an Indian writer based in Mysore. The title 'Navaratna,' which means 'nine gems,' was conferred by the pontiff of the Uttaradi Mutt for the scholarly services he rendered to the Madhva Society by the nine scholar-brothers in that family (in the 17th century).

[2] Technically called ‘circumambulation’ in English, it refers to a clockwise movement around something worthy of worship.

[3] A ceremony that is typically conducted twelve days after the death of a person; it signifies the end of the mourning period. In some communities, it is also a day of celebration for the family members of the deceased person, who has now been sent to the higher realms through prescribed rituals.

[4] The original has ‘upāya tatparate;’ ‘upāya’ has meanings like ‘means,’ ‘remedy,’ ‘plan,’ ‘stratagem,’ ‘effort,’ ‘exertion,’ etc. while ‘tatparate’ can mean ‘intent,’ ‘devotion to,’ ‘interest in,’ etc.