Note: This is the full text of the author’s address delivered on the occasion the launch of the Mysore Hiriyanna Library, a set of reprints of M. Hiriyanna’s books and essays, published by Prekshaa Pratishthana.

At the outset, I take great pleasure in extending a very warm welcome to all of you.

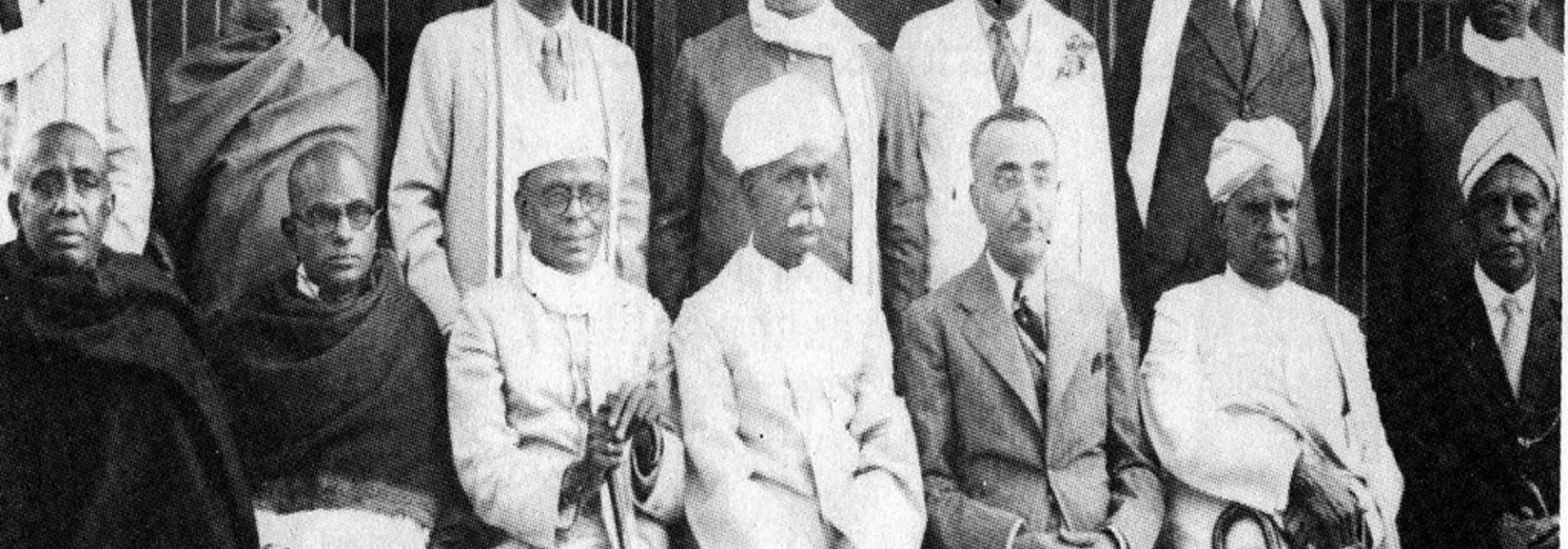

I really don’t know how to begin. The three people here: Hari, Arjun and Shashi have stolen all my lines. But let’s just say that I’ve mixed feelings about this. On the one hand, it is quite an adventure on my part to even attempt to be talking about Acharya Mysore Hiriyanna when I recall the kind of luminaries who have known him, interacted with him, learned from him, and written about him: stalwarts like DVG, Dr. V Raghavan, Prof K. Krishnamurthy, Shri A.R. Krishna Sastri, T.N. Sreekantaiah, and in our own time, Pujya Sri S.R. Ramaswamy and Shatavadhani Dr. Ganesh, among others. On the other hand, it is also my great fortune and honour to attempt a few words on this sage of Indian philosophy out of a feeling of devotion and reverence.

Any mention or discussion or writing about Acharya M Hiriyanna’s glorious legacy will be incomplete and unjust if it examines only some or a few facets. His contribution and legacy is akin to Sanatana Dharma: whole and all-encompassing. Acharya Hiriyanna was and remains one of those rare scholars whose life, work, scholarship and personality are akin to the glow reflected by a prism no matter from which perspective you look at it. This glow in a way, is also reflected by every student and contemporary of M. Hiriyanna, who reserved the same admiration and reverence for his personality as much as his learning and insights. Of all the tributes that he earned, I have selected just two.

The first is by a direct disciple of Acharya Hiriyanna, Sri P.T. Narasimhacharya, who provides a very reverential picture of his Guru:

Guru Hiriyanna was a Sthitaprajna in every sense of the term. He exhibited the quality of an Abhijatapurusha—one who gives his gifts in such a way that none except the donor knows it; in whom fortune does not breed arrogance; and who is intensely devoted to learning. To me, Guru Hiriyanna is an ideal Indian, rooted in his own culture; he did not allow western thought and culture to destroy his identity as an Indian.

This in a way is a good place to begin our discussion on the contemporary—rather I would say, the eternal relevance of Acharya M. Hiriyanna.

The second tribute is by the iconic DVG in his inimitable, intimate and insightful profile of M. Hiriyanna in his Jnapaka Chitrashale volumes. It is also my personal favourite, which brilliantly showcases the learning and personality of M. Hiriyanna. Especially the portion where DVG vividly brings to life the sort of preparation that Acharya M Hiriyanna undertook to explain the precise meaning and import of just word, nIlalOhita makes for a thrilling read.

One major reason why Acharya M Hiriyanna continues to remain relevant relates to how he was the ideal teacher or Acharya—in the truest sense of the word—till the very end of his life. He was the scholar’s scholar and the preceptor’s preceptor, producing at least two generations of scholars and teachers such as T.N. Sreekantaiah, Yamunacharya (who was also the teacher of Dr. S L Bhyrappa), N. Shivarama Sastri, A.R. Krishna Sastri, P.T. Narasimhacharya, and G. Hanumantha Rao among others. He also guided a brilliant scholar and an expert on Indian Aesthetics, Dr. V Raghavan. These scholars were the real-life examples of Acharya M Hiriyanna’s immortal line that the “true aim of Indian education is not to inform the mind but to form it.”

Acharya M Hiriyanna’s teaching knew no retirement age. At a deeper level, M. Hiriyanna as a preceptor and Acharya reveals to us living today a glaring virtue; glaring because it is a largely absent—the virtue of Vyaktiprabhava or the sheer force of personal conduct of a teacher. N. Shivarama Sastri observes in his tribute to his Guru how M Hiriyanna’s students knew more about him than his own relatives. It is for this reason also that he was widely revered as the Sage of the Maharaja College, Mysore. No student or seeker of knowledge who came to him returned with an empty stomach.

To earn this kind of eminence is no small feat when we consider the fact that M Hiriyanna lived in the prime of the era of what Shatavadhani Dr. Ganesh calls the Modern Indian Renaissance (roughly the century between the mid 19th – mid 20th century), which was populated by such colossuses as P.V Kane, Balagangadhara Tilak, R.G. Bhandarkar, Ganganath Jha, V.S. Sukhthankar, S. Kuppuswami Sastri, and traditional Pandits like Kunigal Ramasastri, Hanagal Virupaksha Sastri, Bellamkonda Ramaraya Kavi, etc.

At the present time, Acharya M Hiriyanna is perhaps one of the best models and guides available to us to study and learn about the erudition, art, and craft of how we can reinvigorate and preserve the continuity between the best ideals and traditions of Sanatana Bharata and respond to ideas informed by the onslaught of Western ideas and fashions. Indeed, few scholars and thinkers of his era had the ability and equipment to make Sanatana wisdom and philosophy ever-relevant, in a timeless sense, to any age with such economy of words, lucidity of thought and such grace in expression.

Thus, for example, when he writes that “Vedanta is the art of right living more than a system of philosophy,” we are left speechless at the simple, truthful profundity of this statement. We also intuitively grasp the truth that it takes a lifetime of dedicated penance to arrive at such simple profundity. In fact, an honest study of Acharya M Hiriyanna’s body of work is a great education in itself as to how to think and write clearly, patiently.

Then, there is another sphere in which Acharya M Hiriyanna not only becomes relevant, he urgently becomes inevitable—today more than ever before. This is in the domain known as Indology, Indic Studies and such other abhorrent terminology applied to a truly noble discipline, which should be called by its proper name: Bharatiya Vidya. Today, this field resembles a political and ideological battlefield and not an academic discipline by any definition of the term. Over the last seven decades or so, it has largely been hijacked by Western political, imperialistic and bigoted ideologues and their Indian foot soldiers. Barring a handful, there is a near-vacuum of authentic and penetrating scholarship that can counter these ideologues and offer an authoritative and genuine “native” alternative rooted in truth.

When we contrast this sad scenario with the calm, confident, and systematic manner in which Acharya M Hiriyanna debunked a long queue of Western indologists beginning with Max Mueller, we can only remain wistful. Indeed, Hiriyanna’s stoic but stinging rebuttal of Max Mueller’s arrogant claim that the “Hindu mind had no conception of beauty in nature” is a pioneering critique and a classic in its own right. To set the record straight, it should be said that what Max Mueller exhibited was not scholarship but imperial arrogance rooted in racism. Indeed, the glaring trait and lacuna of Western Indologists right from Max Mueller up to Diana Eck and Sheldon Pollock is this: a clinical coldness; it is an emotional opacity that admits no light because their approach to studying Indian traditions, culture, and philosophy is that of a zoologist who is trained in and skilled at cutting up and dissecting a living frog. Or it is the approach of a Museum curator or an archeologist who digs up dead things.

In fact, Acharya M Hiriyanna had himself warned of this in his own lifetime in his characteristic style more than eighty years ago:

Owing to the impact of hostile forces and the growing secularization of life, there is a great risk of the true Indian ideal being obscured and even lost.

Which is why he called for a “class of patriots” who would honestly, patiently, study and “interpret the past so as to throw light on the right manner in which Bharata’s reconstruction should proceed.”

At this distance in time, we can confidently say that Acharya Hiriyanna’s body of work and legacy are themselves fine models of how this reconstruction should proceed. Hiriyanna’s work is mandatory reading especially for (well-meaning, no doubt) people who seek to understand Indian philosophy through miracles, mysticism, and meaningless quest for dates and phenomena rather than a quest for perfection that Acharya M Hiriyanna has poignantly expounded upon. The model and the precept set by this Acharya, the training that he espouses is compulsory in the contemporary period if we wish to develop cultural self-confidence.

Sadly, this approach was largely ignored due to various reasons, and in the last thirty years or so, we continue to churn out all kinds of theories and indulge in pointless intellectual acrobatics. Further details on this are unnecessary.

Finally, there’s an even profounder and fundamental reason why Acharya M Hiriyanna is relevant not just in the contemporary period but in a timeless sense as I mentioned earlier: for the sheer optimism he inspires. We can quote his own words:

The procession that went forth in the age of the Mahabharata and later passed out of sight is now returning.

This level of optimism infuses great strength, inspiration, and motivation, and I’ll take the liberty of saying that the reprint of these volumes of Acharya M Hiriyanna (the Mysore Hiriyanna Library) on this occasion is because of this selfsame inspiration.

Acharya Mysore Hiriyanna produced his body of unparalleled and pioneering work in an India colonized by the British. I shall leave the rest unsaid.

Thank you very much.