Luminous Personality

I have seen DVG from close quarters for about twenty-five years. In all these years, I have never once seen his intellectual enthusiasm or his method of intellectual inquiry come to a halt. His personality was truly luminous. It felt as if the more I observed, the greater was its expansiveness and depth. As the years rolled by, DVG’s old friends—friends for decades—began to pass away one after the other. This would cause him distress from time to time. In one such mood, DVG wrote a letter to V.C. sometime in mid-1970: “A Jnani has been described as an ekākī nispṛhaḥ śāṃtaḥ -- alone, detached and tranquil. My friends kicked the bucket one after the other. Now I have attained aloneness. However, I haven’t achieved detachment. Perhaps it might come in future.”

In his series of memoirs, DVG has recollected the people who bore a great influence and impact on shaping his mind since childhood: K. Ramachandra Rao, K.A. Krishnaswamy Iyer, M.G. Varadacharya, D. Venkataramayya and others. All of them are truly extraordinary people viewed from any perspective. However, the fact that DVG actively sought their company indicates the magnanimity and spiritual yearning that was innate in his nature.

The chief reason for DVG’s deep respect for the High Court (it was known as the Chief Court back then) Judge H.V. Nanjundayya was the largeness of his heart. Even with regard to convicted criminals, Sri Nanjundayya showed magnanimity and would reduce the severity of punishment as far as possible. This was his argument: “He may have committed a mistake. However, the fruit of the punishment that we award him will be suffered by his wife and children. Poor things, what mistake have they committed?”

When DVG was involved in the renovation of his house, he had the opportunity of getting acquainted with an old man.

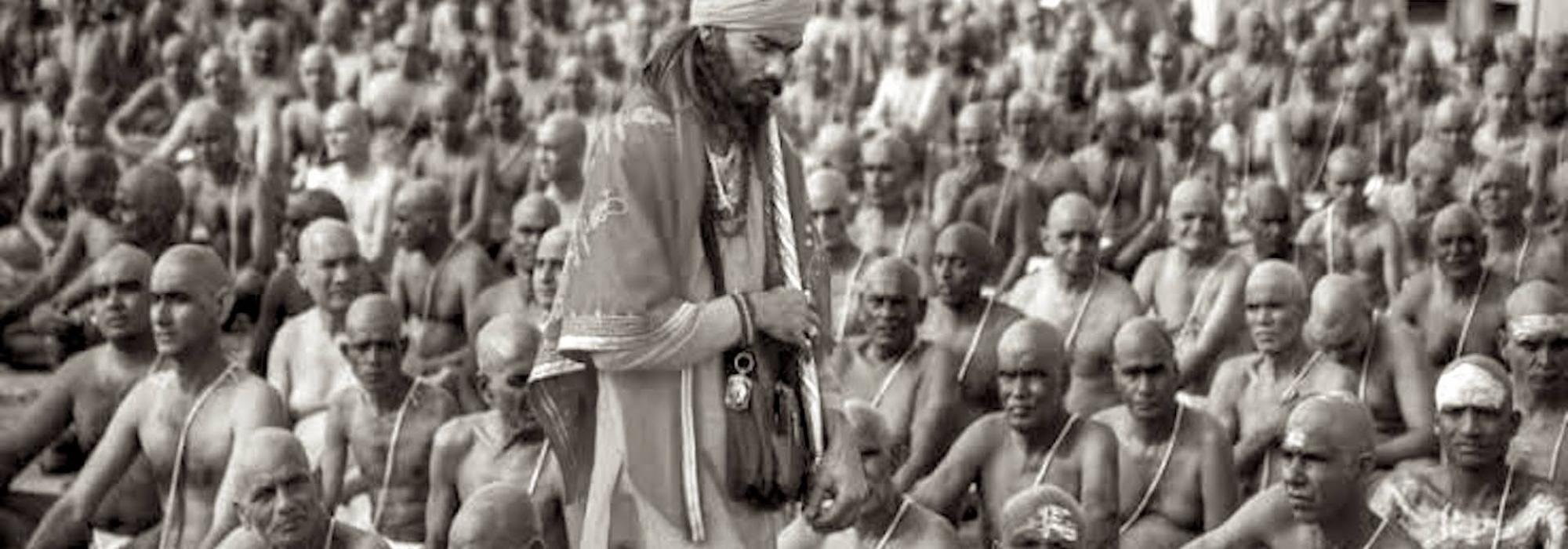

His name was Shivapicchai Mudaliar. His profession was that of a mason but his inner calling was that of a wandering mendicant. A pair of clothes that covered his body, ten or fifteen rupees for the bus or train fare, a trowel, a weighing stone, a peg and other implements—he would be armed with just this and board either a train or bus. He would get down at its last destination. If he found some construction work there, he would remain until he finished it. If there were some temples in that place, he would have a Darshan. After this, he would depart for some other town. He had no fixed rule of going to a predetermined place. He would take up work only when his pockets were empty. Once he had earned enough money for train fare, he would set out for a Tirtha-Yatra. In this manner, he visited all sacred places of pilgrimage throughout Bharatavarsha.

Shivapicchai Mudaliar received his spiritual initiation at the hands of Vakulabharana Paradeshi, a Sadhu hailing from the Andhra region who stayed in Halasuru [Ulsoor].

When DVG asked, “Sri Mudaliar, when do I see you next?”, he said, “When the Swami arranges it.” DVG: “Which is the next place in your Yatra?” He said: “In whatever direction God points me to.”

DVG would recall this and say, “This particular experience is far greater than all the experiences I acquired through books. It is unforgettable.”

DVG’s close friend, Gorur Ramaswamy Iyengar, in his famous work, the essay collection titled Garudagambada Dasayya, has vividly described the different kinds of Dasayyas. DVG had asked Sri Gorur to introduce him to a few of them. DVG would repeatedly praise the absolute inner security and freedom of Dasayyas, Jogis, Bairagis and Fakirs.

We are wanderers, leave us free from the

Troubles of the town, friends |

We come from afar, stay in a Chattra in your town

And move forward today, friends ||

DVG had penned this Wanderers’ Song [Daarigara HaaDu] as early as 1922-23 itself. From one perspective, this song can be regarded as an exposition of his nature. The root of his independence of thought, undeformed mental composure, intrinsic quality of holism, and other lofty traits can be traced to his immersion in spirituality. The socio-political environment or the fear of his opponents did not bother or deter him. His vision akin to the Wanderers encompassed the horizon. The strength of his character emanated from this all-encompassing vision; from that strength emanated his fearlessness and sturdiness of inquiry and examination. To the Wanderers:

There is no obstinacy to accomplish something,

No fear that the path is so tough |

Within the Inner Life we lean upon the Word of the Guru

And take delight in their sayings, friends ||

It is therefore unsurprising that the life of any person within whom this standard of self-confidence, straightforward and transparent conduct resides, will be magnanimous, pleasant and sweet.

It was the aforementioned verse that was greatly dear to V.C. He would constantly recall it; he had translated it to English as well.

***