In the realm of Advaita Vedanta, the term Maya has a popular analogy with Mārīcikā.

mṛgatṛṣṇāmbhasi snātaḥ khapuṣpakṛtaśekharaḥ |

eṣa vaṃdhyāsuto yāti śaśaśṛṅgadhanurdharaḥ ||

This son of a barren woman had bath in the water of the illusion of the desert, decorated himself with the flowers of the sky and is coming towards us holding the bows and arrows of the horn of a rabbit.

In this depiction, all elements are imaginary; nothing is real. They are not realities but mere appearances. Likewise, the import here is that even the world is just a mere appearance or a tradition of illusion.

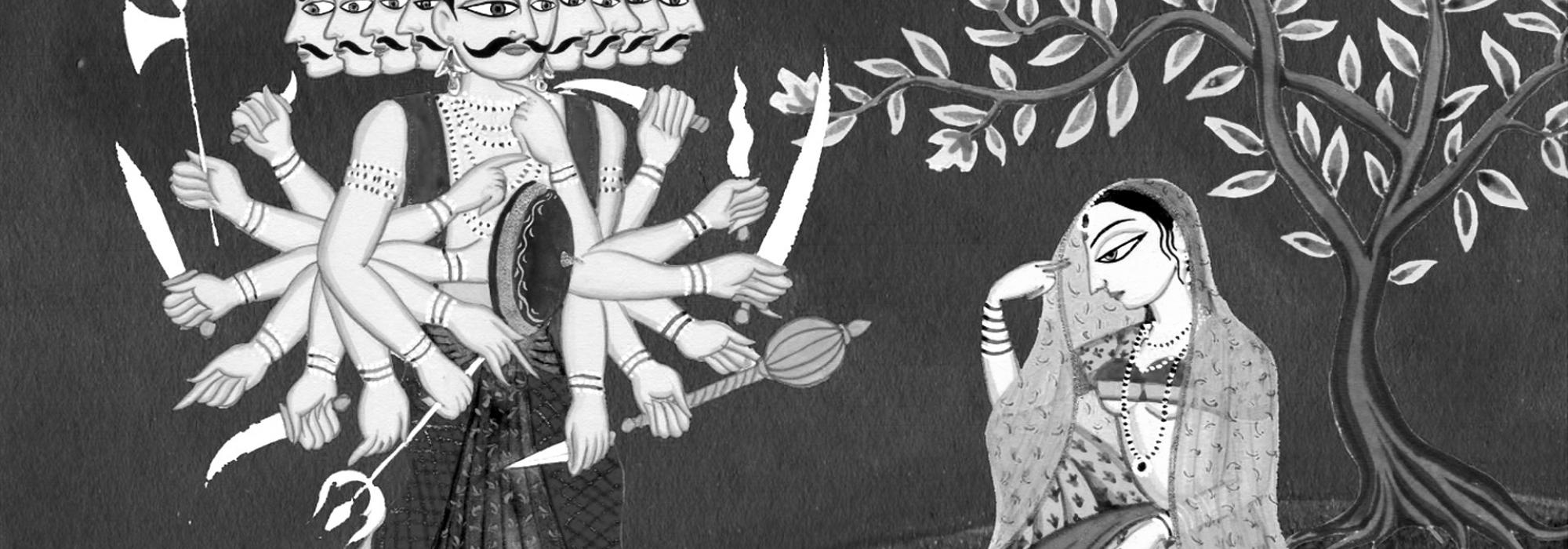

During the same time as the killing of Marīca, in another region, that is in the very ashram of Sri Rama, Sita was abducted by Ravana. In this instance, the reader must read the argument between Sita and Ravana (Sargas: 47, 48).

Upon returning to his ashram, when Sri Rama doesn’t find Sita Devi there, he becomes upset. Then, the manner in which he blames Lakshmana should always be borne in our mind. On that occasion, the kind of bind of Dharma that Lakshmana was caught in reminds people of similar dichotomies that occurred in their own lives. For Lakshmana, on one side, there was the anger of his sister-in-law and on the other, the fury of his brother. Whose words should he have obeyed? Both their arguments were justified from their own individual perspectives. However, in their anxiety, it occurred to neither of them that even Lakshmana might have had his own perspective. The servant of Dharma, in this manner, will on many occasions, be subjected to the red eye of both parties. The person who is endowed with an unswerving vision on Dharma alone will need to set aside the words of both parties and tread on the path that he feels is the righteous one. The noblest trait of Lakshmana was that he bowed down to both these worship-worthy souls and confronted them and conducted himself according to the voice of his conscience. His independence, and his conviction in Dharma must always be remembered by people who are rooted in Dharma.

The story following this is the search for Sita. In this episode, the natural beauty that Rama and Lakshmana savoured during their journey is described by Maharshi Valmiki in truly enchanting verses. The Aranyakanda closes with Rama and Lakshmana reaching the Pampa Lake in the Karnataka country.

****

Overall, Karuna (compassion) is the dominant Rasa of the Aranyakanda. It doesn’t mean other Rasas don’t exist; they do. There is a smattering of Vira (heroic), Adbhuta (wonder) and Shrungara (love).

Equally, it doesn’t mean that there is no Karuna Rasa in other Kandas. In both the Ayodhya and Uttarakandas, Karuna Rasa flows like successive rivulets. However, in the rivulet of Aranyakanda, Karuna has become a flood.

What does compassion mean? It is the quality that makes us say, “Oh no! Poor thing!” when we witness the difficulty of another person. It is also known as sympathy.

Two inner impulses operate jointly in providing impetus to compassion. These are the true impulses innate within every human being. One is self-experience; the second relates to justice.

If in some situation we experience either joy or sorrow, we automatically regard another, similar situation as causing either joy or sorrow. This conduct emanating from self-experience is the foundation for all human bonds. That which hurts our body also hurts others’ body as well. That which is sweet to our tongue is similarly sweet to that of others. We caress our own back and then rub the back of others. We pinch ourselves first and then go pinch others. This behaviour drawn from self-experience is the first part of acquiring worldly knowledge. Its shadow known as our voluntary acceptance of the self-experience of others is the second part. When others are undergoing suffering, we join in their suffering. We make the sorrows of other people our own. We become participants in the joy and sorrow of others. This is sympathy. It is compassion, pity, and mercy, the realization of the experience of others through self-experience.

After realizing the feelings of others, we become partners in their experience. This is the root of the behaviour that exhibits soul-similitude. And soul-similitude is the inner secret of working for the world’s welfare.

Ātmaupamyena sarvatra samam pasyati yo'rjuna |

sukham va yadi va duhkham sa yogī paramo mataḥ| | (Bhagavad Gita: 6:32)

Compassion and sympathy are the works of the heart. What should be joined to them is the work of the intellect that distinguishes between the right and the wrong, the relevant and the irrelevant. Under what circumstance is compassion applicable, and to what extent? This is a matter of fairness. Compassion should be just. Justice derives from the distinction between the deserving and the undeserving. Hunger is difficult to bear for all of us. However, between the hunger of a three year-old child and a strong youth of thirty, whose difficulty is greater? The greater compassion flows to the person whose capacity to endure difficulty is lesser. A journey in the jungle is certainly strenuous for all of us. However, the strain is more pronounced for a person who is used to the luxury of the palace. In this manner, we distribute compassion according to the strengths and weaknesses, and needs of the person in question.

In the case of Sita Devi, there are numerous reasons that evoke our compassion. A woman and helplessness – these are universal reasons for said compassion. Let’s set them aside and look at other reasons. (1) She is the daughter of a Maharaja and the daughter-in-law of a Maharaja. She’s unaccustomed to difficulties. Can such a fate befall her? (2) She is a Tapasvini. She is steadfast in the vows of Truth, self-restraint and non-violence. Such trouble for such a person? (3) That too, at the hands of a totally evil man? (4) And what is the nature of her hardship? A mortal threat to her lifelong vow of purity of the senses? When we consider these aspects, our mind naturally melts and we join in Sri Ramachandra’s piteous cries.

There is a tiny seed that anticipates justice in all episodes that evoke our compassion. Sri Rama was endowed with such an expectation of justice. By nature, he was a jovial person. His mental outlook was one which was immersed in the gentle beauty present in nature. Maharshi Valmiki has used charming colours to paint a picture of the mind of such a person.

krameṇa gatvā pravilokayan vanam

dadarśa paṃpām śubha darśa kānanām ।

aneka nānāvidhapakṣijālakām ||

It is already said that in compassion, there is an innate feeling of oneness in the hardships of others and in giving justice to the aggrieved person. It is for this reason that compassion transforms to sorrow. “Oh no! What a fate Sita Mata has to undergo! What a great travesty! How cruel!” – we bewail on these lines. There is an exalted feeling of humanity in this sorrow. That is why it becomes endearing to us and becomes Rasa. We repeatedly turn to such episodes out of curiosity. In this manner, the tragedy Rasa of poetry becomes a distillation of our own lives. Recognising this, the philosopher Aristotle has said that tragedy is catharsis. The more we sympathise with Sita by constantly invoking her name, the greater is the refinement of our heart.

Concluded