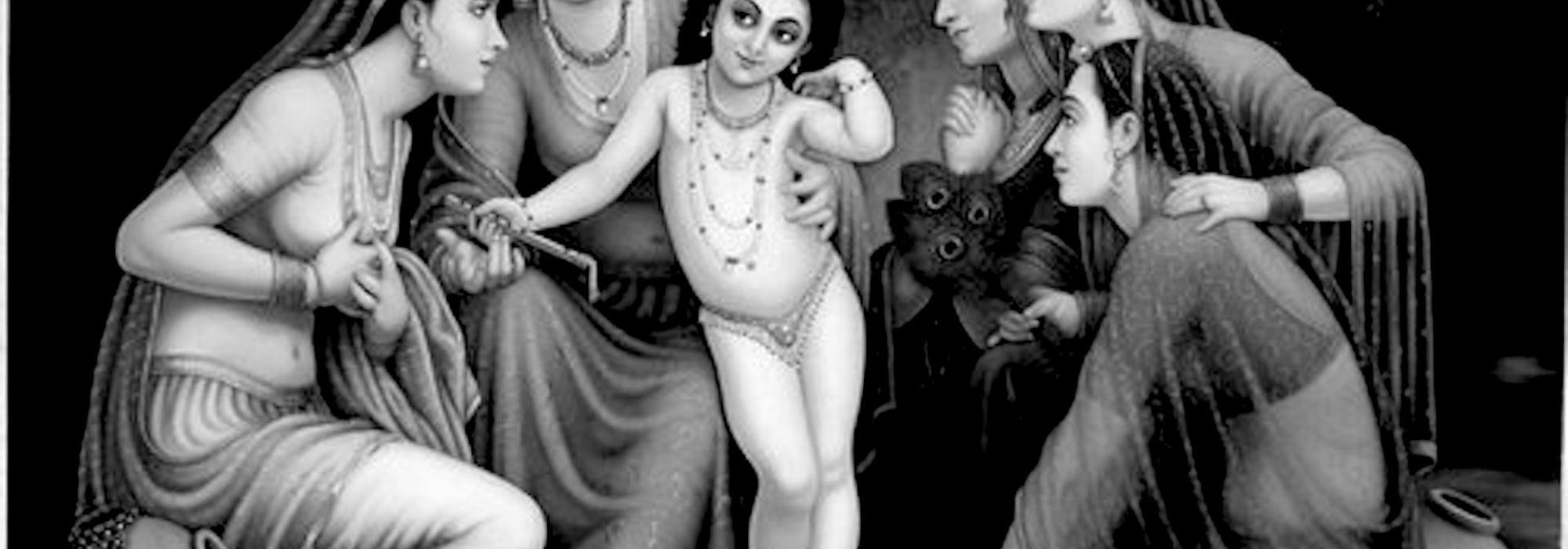

Since childhood, Krishna continued to reveal his divinity at every turn. Every danger that he encountered were splintered into pieces akin to thick clouds in the face of a typhoon. No matter the gravity of the threat, he never lapsed into worry even for a single moment. He regarded the world as a plaything and conducted himself accordingly. There is no rule that says that the conduct of divine beings must be acceptable to us although their teachings are enlightening. Sri Rama conducted himself entirely like a human being. He was consonant with the common rules of the world and Sastric dictums and lived his life accordingly. Never once did he cross the line of Dharma. However, Krishna was genuinely otherworldly. He became the cause for Sastras. The line of Dharma is applicable to people who are bound by Karma and not to Devatas. Who can draw the line of Dharma to a divinity that proclaims, “na māṃ karmāṇi badhnanti na me karmaphale spṛhā?”

A question must be posed to the modernists who object to Krishna’s conduct: “How did you learn of Srikrishna’s dalliances with the Gopis?” Their answer: “It is written in the Bhagavatam.” To which we ask: “The selfsame Bhagavatam also says that Srikrishna was the Paramatman incarnate and that he is not bound by any Karma.” To this response, their reply will be in violation of all rules of logical debate. They are incapable of responding honestly.

It is my conviction that the Gopika episode was inserted by the Bhagavatas in order to expound a certain nuance of Dharma. But for that, they would have omitted the Gopika episode entirely. Indeed, who really forced them to include it?

The Bhagavatam says that even the sworn enemies of Krishna such as Shishupala attained Moksha through the constant contemplation of Srikrishna. In which case, was it Dharma on the part of Prahlada who rebelled against his own father? Was it Dharma on the part of the hunter Kannappa who touched the Shivalinga and placed his feet on it? The truth is that in the Empire of Bhakti, there are no rules and restrictions. Bhakti by itself is the greatest Dharma which burns all rules and restrictions to ashes. In essence, the unflinching love of the Gopis is just another facet of the most exalted Bhakti towards Bhagavan.

In my opinion, the eleventh and twelfth Skandas of the Bhagavatam are the most important. The philosophical tenets spread over this Great Purana in other Skandas have been presented in these two Skandas in their best essence. Srikrishna has discoursed the essence of the Vedanta to Uddhava in these Skandas. These mark the closure of Srikrishna’s Avatara. At this stage, this is his final discourse delivered to his most favourite friend, disciple and devotee, Uddhava. The Bhagavan kept Uddhava merely as an excuse and gave his immortal message of divinity for the benefit of the world. It is also his great benediction. Additionally, this is the same message that the Rishis Shuka and sūta-purāṇika preached in consonance with the Bhagavan’s discourse.

Chapter 6: Sri Vishnupurana and Sri Bhagavatam

Among the ten renowned Avatars of Mahavishnu, the Vishnupurana narrates details about the five famous ones, namely, Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrsimha, Srirama and Srikrishna. Among these, the story of Srikrishna appears extensively. The episode where Nrsimha slays the demon Hiranyakashyipu occurs only incidentally. Although this episode indicates the glory of Bhakti, the story is not elaborated. However, in the Bhagavatam, all these episodes are narrated in a detailed fashion. It may be recalled that the Bhagavatam was composed to explicitly uphold the greatness of Bhakti. The hymns related to Vāsudeva and others in the Caturvyūha (literally, “four emanations” of Vishnu) occur in both puranas. The similarities between both these puranas are marked with respect to matters such as their premises and philosophical expositions. It is not incorrect to say that the Bhagavatam is the exalted detailing of the Vishnupurana.

The Greatness of the Bhagavatam

The Bhagavatam has occupied the topmost spot of honour among Puranas and remains popular. The Bhagavatam itself declares that it is the distilled essence of the entire Vedantic corpus. The Padmapurana says that the Bhagavatam is the fruit filled with the juice of Amruta which dropped from the Kalpataru of Vedanta. Indeed, the sheer number of commentaries on the Bhagavatam is itself proof of its eminence and popularity. As of now, thirty-five commentaries are available. Among these, Sridhara Swamin’s bhāvārthadīpikā, Veeraraghavacharya’s bhagavatacandracandrikā and Vijayadhvaja’s padaratnāvalī remain the most acclaimed commentaries, respectively belonging to the Advaita, Dvaita and Vishishtadvaita schools. And then, Vallabhacharya’s subodhini is another notable commentary belonging to the Shuddhadvaita school. In the thirteenth century CE, a famous Vidvan named Bopadeva earned extraordinary scholarship in the Bhagavatam and authored a commentary titled harilīlāmruta. Although it reads like a table of contents of the Bhagavatam, he has captured the essence of the philosophical hypothesis of the work. This work has a commentary by Madhusudana Saraswati.

The eminence of the Bhagavatam lies in its showing us the easiest path to realize the Paramatman. The Bhagavatam clearly demonstrates the fact that the path of Bhakti is the easiest as far as ordinary people are concerned. The Bhagavatam contains a section that says that Veda Vyasa was not satisfied even after composing the Mahabharata and that his heart found fulfilment after authoring the Bhagavatam. The section in the Padmapurana that extols the glory of the Bhagavatam avers thus: when Bhakti is not given enough prominence, both Jnana (Pure Knowledge/Realization) and Vairagya (Renunication) lost their strength and eventually decayed. They were revived after Bhakti regained its primacy only after listening to the Bhagavatam. The summary of this is as follows: Jnana and Vairagya, the vehicles for attaining Moksha will be spurred into action only through Bhakti. The story of Prahlada shows the innate necessity of Bhakti. The Bhagavan is pleased more quickly by Bhakti than through conduct, charity and penance: “priyatenanyayā bhaktyā hariranyadviḍambanam.”

Likewise, the Bhagavatam also teaches the Yoga of non-attachment in which the devotee must sincerely perform his Karma and offer the fruits thereof to the Bhagavan. Karma supplies the purity of consciousness required for attaining Jnana. However, the path of Karma must essentially be accompanied by Bhakti. If the efforts that a person invests towards attaining Jnana are not imbued with Bhakti, all such efforts will be fruitless and will bring sorrow. Bhakti is nine-fold: śravaṇa, kīrtana, smaraṇa, pādasevana, arcana, vandana, dāsya, sakhya, and ātmanivedana. Or listening intently (to Bhagavan’s name and glories), singing, contemplation, feet-worship, homage, salutation, servanthood, friendship and offering of the Self. Indeed, even Moksha is not as enjoyable as Bhakti. Indeed, a genuine Bhakta does not want Moksha and wishes to remain an eternal devotee. In this fashion, the Bhagavatam extolls the infinite joy of Bhakti.

ātmārāmāś ca munayo nirgranthā apyurukrame|

kurvantyahaitukīṁ bhaktimittham bhūtaguṇo hariḥ || (1.7.10)

To be continued