Telugu literature is known for its dexterous use of Sanskrit. While the language of the gods is a brilliant but hard diamond for many, it becomes supremely malleable for Telugu poets who weave their lyrical magic in it. This deft use of Sanskrit extends even to Telugu movie songs whose lyricists are not mere commercial song writers but poets in the truest sense of the word.

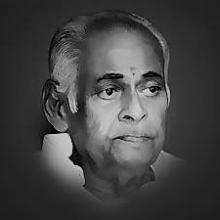

A prominent name here is that of the late Sri Veturi Sundararama Murthy who has exhibited his virtuosity in many a lyric. One particular song that came to mind this morning is the classic Omkāranādā.., the title song of K Visvanath’s trendsetting cinematic paean to classical music, Śaṅkarābharaṇam. In this brief piece, I just want to share the joy found in the Sanskrit-enriched lyrics of the title song. Though there are meanings found on the internet for this song, this is a personal journey through the delight of that song-river.The word Śaṅkarābharaṇam, literally meaning an ornament of Bhagavān Śaṅkara (Śiva) is also one of the most well-known rāgas in Karṇāṭaka music — the twenty-ninth melakarta. Several wonderful compositions abound in this rāga that is true to its name. The present song, too, is set in the same rāga by the maestro K V Mahadevan, whose musical magic can mask lyrical brilliance. And last but not the least, the melodious rendering of this song by the legendary playback singer S P Balasubrahmanyam just adds to the overall effect of the song. This note will deal only with the sāhitya, lyrics.

Oṅkāra-nādānu-sandhānamau gāname Śaṅkarābharaṇam — The song that is the contemplation of the oṅkāra is Śaṅkarābharaṇam — a literal adornment of Śaṅkara. The word Śaṅkara literally meanings “the one who brings or causes auspiciousness.” While Śiva also means auspiciousness, Śaṅkara also implies activity — kara — embedded in the word. This starting line refers equally well to both the rāga and an ornament of Mahādeva — both are the result of contemplation upon Oṃkāra — the primordial praṇava.

The song now features a bunch of viśeṣaṇas (adjectives) while the viśeṣya (noun) is Śaṅkarābharaṇam, the rāga or the ornament.

Śaṅkaragaḻa-nigaḻamu — literally the chain in Śaṅkara’s neck. Gala means neck, and nigala means chain. Gala-nigala not only adds a lilting alliteration, but also bring about some charming allusions. The first thing that comes to mind when we think of Śaṅkara’s neck is obviously Vāsuki, the king of snakes. Coiled snakes such as the one around Siva’s neck denote the divine risen energy of Kuṇḍalinī. Nigaḷa or nigaḍa (ḷa and ḍa are used interchangeably) means a fetter used to contain or control. With that meaning, it appears that the poet chooses to say that this rāga is a literally a fetter to contain Śaṅkara — listening to which even Paśupati follows meekly like a Paśu! In his attempt at rhyme, the poet has created a novel image.

Śrīhari-pada-kamalamu — Compared to the previous word, this is a little straightforward — “The lotus feet of Śrīhari — Bhagavān Viṣṇu.”

The antyaprāsa (concluding rhyme) in — gala-nigalamu and pada-kamalamu is wonderful to listen to. Also, this shows that the rāga, though an ornament of Śaṅkara, is pleasing to both Śaṅkara and Śrīhari!

Rāgaratna-mālikā-taraḻamu — The first three words in this samāsa (compound) are straightforward — rāgaratna-mālikā — the garland of rāga-jewels. However, the word tarala shows the poet’s felicity with Sanskrit. While it means fickle and shining, it also refers to the central gem in a necklace. Putting this together, this compound means that Śaṅkarābharaṇam is the pendant jewel in the rāga-necklace. Many connoisseurs of music will agree with the poet. It is one of the rāgas that can be sung extensively, and its notes form the most commonly used C-Major scale of Western music.

Again, the antya-prāsa in nigalamu-kamalamu-taralamu is sonorous!

The next stanza is another treasure-trove of poetic expression. Note that the viśeṣaṇas for Śaṅkarābharaṇam are still continuing.

Śārada-vīṇā-rāga-candrikā-pulakita-śārada-rātramū — These are the kinds of phrases that Raja Bhoja would gladly give akṣara-lakṣas for! Śārada-vīṇā-rāga-candrikā refers to the moonlight that is the rāga issuing from Śārada’s i.e., Sarasvatī’s vīṇā. The next half of the compound is pulakita-śārada-rātramu — a delighted śārada-rātramu. Here śārada refers to the śarat-kāla which is known for its moonlit cloudless skies. The entire phrase now means that (Śaṅkarābharaṇam) is like the night of the season of śarat that is delighted by the moonlight of Goddess Sarasvatī’s vīṇā playing!

Note that the season of śarat is also the season of Navarātra when Goddess Sarasvatī is also worshipped as an aspect of Śakti!

Nārada-nīrada-mahatī-nināda-gamakita-śrāvaṇa-gītamū—another beauty! Nārada-nīrada-mahatī-nināda refers to the sound (nināda) of the mahatī (the vīṇā of the itinerant Nārada) emanating from the cloud (nīrada) that is Nārada. Making Nārada a cloud and his famed vīṇā mahatī the cloud’s nināda is a lovely, novel image. Here nināda not only refers to meghadhvani (the rumble of a cloud) but also vīṇādi-dhvani (the music from instruments such as the Vīṇā). The second half is gamakita-śrāvaṇa-gītamū. Gamaka refers to an ornamented note that is quite familiar to most listeners of classical music. An interesting allusion here is to the gamaka-richness of Śaṅkarābharaṇam. Śrāvaṇa here not only refers to the lunar month of but also to hearing (śravaṇa) as well. Both phrases coming together—Śaṅkarābharaṇam is a song of śrāvaṇa / hearing, whose notes are ornamented by the sounds of the cloud / vīṇā of the cloud that is Nārada!

The English translation conveys the total import poorly — how much have I pulled those poor words hither and thither! But put them back together and revel in the sweetness of meaning!

The next three can be taken together as a unit.

Rasikulak(u) anurāgamai — This rāga is not just musical melody but an anurāga for rasikas (connoisseurs)! ‘Anu’ is something that follows. Rāga refers to passion or desire. Anurāga then is something that follows initial desire i.e., love. This rāga is akin to love for connoisseurs!

Rasagaṅgalo tānamai.yī — Having immersed (tānamai — Telugu from Sanskrit snānamai) in the Gaṅgā of rasa / aesthetic essence. Musically, tāna can roughly be called a rhythmic improvisation of the rāga.

Pallaviñcu sāmaveda mantramu — The mantra of the Sāma-veda (the Veda that is the origin of Bhāratīya music) that blossoms.

The consolidated meaning of these three — “It (Śaṅkarābharaṇam) is the love of the connoisseurs, a mantra of the Sāma-veda that blossoms after immersing itself in the Gaṅgā of rasa.” Note that the poet has managed to bring in rāga, tāna and pallavi — the chief vehicle of improvisation in a concert — in this unit without bringing their primary meanings as in a dattapadī!

After a nice musical interlude, the poet introduces some of his interesting thoughts. For some song writers, later stanzas are a bit less attractive than the introductory ones. However, Sri Veturi continues to expand on what he thinks of music in general.

Advaita-siddhiki, amaratva-labdhiki, gāname sopānamū — The individual word meanings here are straightforward — but there is some svārasya in what is being said. The poet says that music is a ladder for obtaining oneness as well as gaining immortality. Note the choice of words in “advaita-siddhi” and “amaratva-labdhi” — while the former is a siddhi (referring to fulfilment / mokṣa — a higher goal), the latter is a labdhi — slightly lower than siddhi. Here “amaratva” can also refer to devatva. In essence, the poet seems to indicate devatva is lesser than attaining advaita or becoming non-dual with existence.

Sattva-sādhanaku, satya-śodhanaku, saṅgītame prāṇamū — Again easier words to understand but a great message is being given here. Sattva is the highest of the three guṇas to be attained while transcending the lower guṇas of rajas and tamas. Satya is the Truth. Sri Veturi indicates that whether it is for attaining (sādhana) the sattva-guṇa or for searching (śodhana) for satya (truth), music is prāṇa — the vital force that animates this search and attainment. In other words, the poet says that neither can sattva be attained nor truth be reached if there is no music to animate both!

Tyāgarāja-hṛdayamai — Being the heart of Tyāgarāja—who is one, if not the greatest—of Karṇāṭaka-vaggeyakāras. I am not sure if Sri Veturi knew this, but interestingly, Tyāgarāja-svāmī has composed most of his kṛtis — thirty — in this rāga! Which means that this rāga is quantitatively Tyāgarāja-hṛdaya as well!

If Tyāgarāja is here considered to refer to the king of renunciation, the Lord of Tiruvārūr, this rāga is aptly considered his heart!

Rāgarāja-nilayamai — Śaṅkarābharaṇa is the abode of the rāja (king) of rāga (passion) — Kāma / Manmatha! It is not for nothing that a musical melody is given the same name — rāga — as for passion or desire.

In the present and the previous stanzas, the poet presents a contradiction — virodhābhāsa! While Śaṅkarābharaṇa is the heart of Śiva — the king of renunciation, it is also the abode of his enemy — the king of passion!

Muktinosagu bhakti-yoga-mārgamu — Words that are easy to understand again. Śaṅkarābharaṇa is the path of bhakti-yoga that bestows mukti (liberation).

Mṛtiye leni sudhālāpa-svargamu — This is the (svarga) heaven of the sudhā-ālapa (nectarine musical enumeration of a rāga) that has no end.

This river of words is followed by an attractive but cinematic svara-prastāra. Overall, the effect of this song is one of lingering joy that has rightly given it a prominent place in the hall of fame of all-time classics.

I am just grateful to be able to enjoy the aesthetic sweetness that these stalwarts have filled in this nugget of rasa.

You can listen to the song again here.

|| iti śam ||