“आचिनोति च शास्त्रार्थानाचारे स्थापयत्यपि।

स्वयमाचरते यस्मादाचार्यस्तेन चोच्यते॥”

“An Acharya is one who consolidates the essentials of a knowledge system, establishes them in tradition, and himself observes them in practice”

Introduction

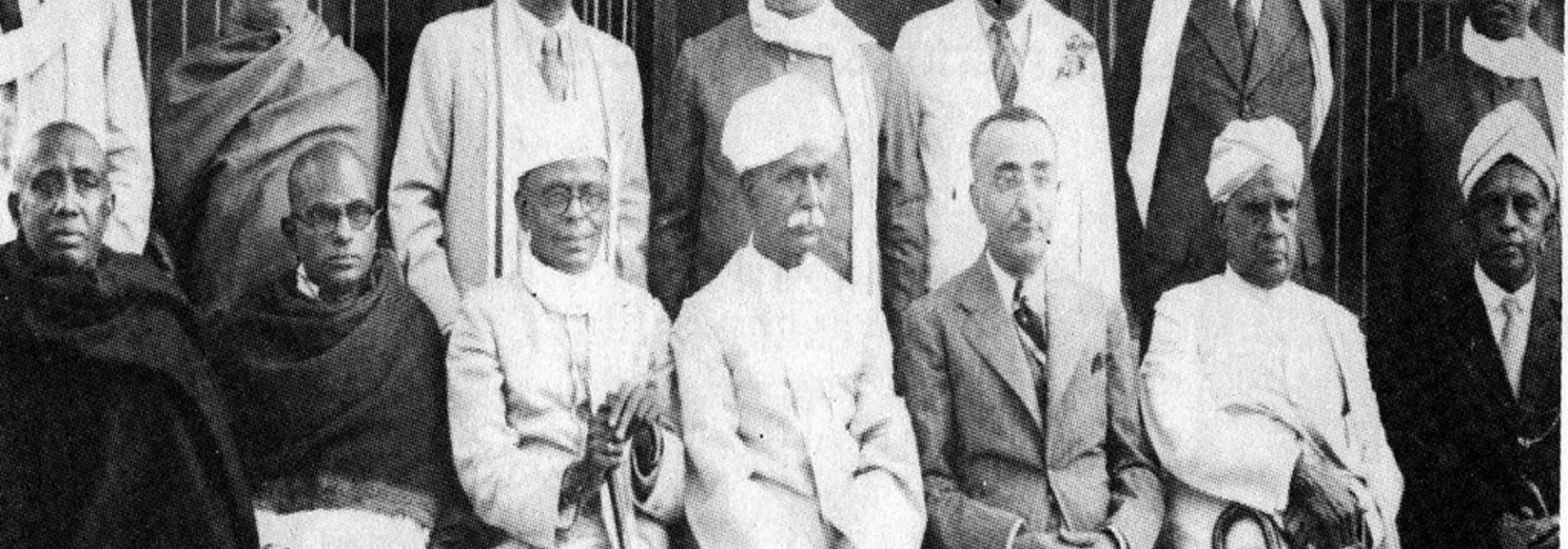

The term ‘Acharya’ is reserved for one who teaches not by mere lecturing, but through the force of his personal conduct. In the context of modern Indian renaissance, there is perhaps nobody who deserves this appellation more than Mysore Hiriyanna (1871–1950).

M. Hiriyanna was a professor of Sanskrit at Maharaja’s College, Mysore. He is considered an outstanding authority of Indian Philosophy and Aesthetics who pioneered the study of these subjects in the twentieth century. His scholarship was a fine blend of traditional Indian and modern western learning. Famously described as a scholar who never wrote a useless word, he preferred depth to width and synthesis to analysis. The purpose of education, he believed, “is not to inform the mind, but to form it.” It is the spirit of this thought that invariably animates all his writings.

At the outset it would be beneficial to briefly outline the nature of the time in which the professor wrote on Indian Aesthetics. It was a period when there was hardly any literature on the subject—not just in English, but all regional languages of India. If this was the case with secondary literature, primary Sanskrit texts themselves were hard to procure. Although Bharata’s Nāṭya-śāstra was first published in 1894, Abhinavagupta’s monumental commentary thereon, Abhinava-bhāratī, was published only in 1926. However, this was only the first volume. Starting then, it took three decades of scholarly effort to bring out the complete text of Abhinava-bhāratī. This, too, is unfortunately not free of errors. The case with Ānandavardhana’s Dhvanyāloka, another seminal treatise of Poetics, is no different. It is in fact worse, for its critical text was made available nearly a century after its discovery (1877)[1]. Many other important texts were still in manuscript form, waiting to be widely circulated and discussed.

If this was the scenario concerning the data available, the academic ambiance, too, was not at all conducive for a scholar to take to the study of Alaṅkāra-śāstra. On the contrary, it was singularly discouraging, because in June 1890, Max Muller—who was considered an authority on all subjects related to India—had proclaimed, “… the idea of the Beautiful in Nature did not exist in the Hindu mind.”[2]

Seen in this background, we understand that Prof. Hiriyanna had to painstakingly go through primary sources, subject the material to a careful process of sifting, and build a solid case for Indian Aesthetics. This he did remarkably well, because starting from 1919, the year in which he wrote his first essay on the subject—which was incidentally published in the proceedings of the first all-India oriental conference—till he passed away in 1950, he wrote a series of articles that threw a flood of light on the Indian conception of beauty.

Usually, when the study of a subject is at an incipient stage, one does not expect to come across an essay or a book that succinctly summarizes all its quintessential tenets. Such an attempt is reserved for a later stage where all its data points are systematically arranged and discussed from various perspectives by multiple scholars. The study of Indian Aesthetics was in such a stage when Prof. Hiriyanna began writing on it. But he had the outstanding acumen to go the heart of the matter immediately. So his book Art Experience advanced the study of Alaṅkāra-śāstra by almost half a century. Needless to say, this is not a minor achievement. In her foreword to the edition of this book published by the IGNCA, Dr. Kapila Vatyayan wrote:

“Each essay illuminates a fact of Indian aesthetics or an aspect of poetics. They are like glowworms in a dark night, flashes of insight in an inimitable style of conciseness and pithy economy of words. There is no weight of heavy or cumbersome scholarship, footnoting or referencing. They thus stand a class apart from all those others whose work is characterized by erudition and information. For the reader, be he a Sanskritist or not, they make engaging reading and are full of contemporary relevance.”

Prof. Hiryanna’s Insights into Indian Aesthetics

The articles that contain the core of his thoughts on the subject are: four essays from the book Art Experience—Indian Aesthetics 1 & 2 and Art Experience 1 & 2; the first lecture on the topic ‘The Quest after Perfection’ wherein he discusses truth, goodness, and beauty; and the essay titled Beauty in Art in his magnum opus, Indian Conception of Values. In all these articles he primarily focuses on the fundamental tenets of Alaṅkāra-śāstra, drawing support from masters such as Bharata, Ānandavardhana, Abhinavagupta, Vyāsa, Vālmīki, Kālidāsa, and Bhavabhūti.

A usual charge leveled against Indian Aesthetics is that philosophers in India did not develop aesthetic theories, as was the trend in the West. Prof. Hiriyanna replied to this allegation by citing counterexamples from philosophical texts such as Sāṅkhya-kārikā and Vedānta-pañcadaśī. More importantly, he showed how Alaṅkāra-śāstra in India developed independent of philosophy—as an autonomous science—and thereby carved a special niche for itself. If philosophy were to be squared with aesthetics, there would be as many theories of art as there are theories of reality, leading to an endless spiral of confusion—thus proceeds his infallible argument.

By all this it should not be understood that Hiriyanna criticized westerners alone and accepted everything Indian as good. Nothing can be farther from truth, for he was very much aware of the lapses or shortcomings in our tradition. For instance, he openly criticized the undue popularity enjoyed by a mere primer of Poetics—Pratāparudrīya or Pratāparudra-yaśobhūṣaṇa—at the cost of Dhvanyāloka, which is sui generis in Indian Aesthetics.

It was Prof. M. Hiriyanna who for the first time provided a clear answer to question: why can’t the Vedas be considered as works of poetry? It is because, said the professor, the Vedas are primarily God-centric (deva-kendrita) whereas poetry proper is human-centric (jīva-kendrita). So the line that separates bhakti (devotion) and rakti (desire, affection, loveliness), so to speak, is the one that demarcates Veda and Kāvya[3].

Regarding the difference between beauty in nature and beauty in art, he decisively explained that while the former may arouse some practical interest in the beholder, the latter can never do so. In his own words, “A person admiring the scenic beauty of a mountain may conceivably be diverted from it at any moment by the thought of some purpose, say, of making the place fit for a health or holiday resort. It may thus become the focus of a different kind of interest; but no such diversion of interest is conceivable in the case of art, because its object is unreal.” (The Quest After Perfection, p. 70). He further remarked: “…Nature, even at its best, contains irrelevant features, if not also ugly and disagreeable ones. To paint a landscape is more than to photograph it. The painter does not reproduce it as it is, but as his imagination represents it to him. In other words, the artist never copies the given mechanically, but idealizes it; and in this idealization lies the secret of his art.” (Art Experience, p. 36) [4]

It was also Prof. Hiriyanna who for the first time provided a cogent argument for the consideration of beauty as a value. He did this in the light of Advaita Vedānta, which speaks of jīvanmukti—liberation from all ties, here and now. The terseness of Hiriyanna’s prose and the gravitas of the subject necessitate quoting his view on this in extenso:

“Beauty in Nature then, as we commonly understand, is anything that brings about a break in the routine life and serves as a point of departure towards the realisation of delight. This is the only condition which it should satisfy. But what is the significance of this break? Generally we lead a life of continuous tension, bent as we are upon securing aims more or less personal in character. In Śaṅkara’s words life is characterised by avidyā-kāma-karma, i.e., desire and strife, arising out of the ignorance of the ultimate truth. When we are not actively engaged we may feel this tension relaxed; but that feeling of relaxation is deceptive for even then self-interest persists as may be within the experience of us all. Delight means the transcending of even this inner strain. The absence of desire then is the determining condition of pleasure; and its presence, that of pain. The absence of desire may be due to any cause whatever—to a particular desire having been gratified or to there being, for the time, nothing to desire. The chief thing is that the selfish attitude of the mind—the ‘ego-centric predicament’—must be transcended at least temporarily, and a point of detachment has to be reached before we can enjoy happiness. Joy or bliss is the intrinsic nature of the self according to the Vedānta, that being the significance of describing the ultimate reality as ānanda. The break in the routine life restores this character to the self. If its intrinsic nature is not always manifest, it is because desire veils it. When this veil is stripped off, no matter how, the real nature of ātman asserts itself and we feel the happiness which is all our own. In the case of a jñānin the true source of this delight is known; but even when such enlightenment is lacking we may experience similar delight. We may enjoy while yet we do not know. To use Śaṅkara’s words again, the ever-recurring series of kāma and karman or interest and activity constitutes life. The elimination of kāma and karman while their cause avidyā continues in a latent form, marks the aesthetic attitude; the dismissal of avidyā even in this latent form marks the saintly attitude. Thus the artistic attitude is one of disinterested contemplation but not of true enlightenment while the attitude of the saint is one of true enlightenment and disinterestedness but not necessarily of passivity. The two attitudes thus resemble each other in one important respect, viz., unselfishness.” (Art Experience, pp. 17–19)

Prof. Hiriyanna was of the firm opinion that the cardinal characteristic feature of art is the transcendence of all purposes. Estimating its value, he wrote: “… art experience is well adapted to arouse our interest in the ideal state by giving us a foretaste of it, and thus to serve as a powerful incentive to the pursuit of that state. By provisionally fulfilling the need felt by man for restful joy, art experience may impel him to do his utmost to secure such joy finally.” (Art Experience, pp. 45). Similarly, he called art ‘Layman’s Yoga’ and wrote in his typical tone of authoritative finality: “Art is a short cut to the ultimate value of life, bypassing logic.” (Ibid, p. 66)

To seek harmony in all spheres of existence is a natural desire of all of us. Prof. Hiryanna beautifully brought to light the Indian idea of accomplishing this—not by extinguishing interests but through refinement of feeling and cultivation of emotion. Speaking of the relation between art and morality, he posited in his inimitable, epigrammatic style: “… art should not have a moral aim, but most necessarily have a moral view.” (Art Experience, p. 77). On a related note, he observed: “Art, rightly conceived, cannot be merely a selfish escape from life. Nor is it a pleasant luxury; it is a discipline, albeit it is pleasant, and must influence life permanently or, at least, tend to do so.” (Indian Conception of Values, pp. 447–48)

He argued that great poetry must essentially deal with puruṣarthas: “Though theoretically the theme of art may be anything which has a basis in life, this additional requirement makes it necessary to restrict the scope of the artist’s choice to the higher aspects of life. Otherwise, art not only ceases to exert any moral influence; it may turn out in the end to a means of corrupting character.” (Indian Conception of Values, pp. 449). As an example, he referred to Bhavabhūti's play Uttara-rāma-carita, which is not just ramaṇīya (beautiful) but also udātta (sublime).

In all his writings, Prof. Hiriyanna threw light on those aspects of the subject that usually create doubts in the mind of the student. As an example we can consider his explanation of the term rasa: “The word ‘Rasa’ primarily means ‘taste’ or ‘savour’, such as sweetness; and, by a metaphorical extension, it has been applied to … (aesthetic) experience. The point of the metaphor is that, as in the case of a taste like sweetness, there is no knowing Rasa apart from directly experiencing it.” (Indian Conception of Values, p. 432). “… rasa is always suggested, but suggestion is not always of rasa.” (Ibid, p. 440). This has to be understood in the sense that although suggestion can manifest itself in three ways—vastu (fact based), alaṅkāra (imaginative), and rasa (emotional)—apart from rasa-dhvani, the rest may not always bring about aesthetic relish immediately[5].

There are numerous passages in ancient texts related to Poetics that on the first glance appear prescriptive, but are truly descriptive in nature. A superficial examination of these might lead one to the incorrect conclusion that Sanskrit poets worked with stultifying rules that did not allow them to freely express themselves. Speaking of this, Prof. Hiriyanna clarified: “… they are to be looked upon more as aids in appraising the worth of a poem … than as restraints placed upon the freedom of a poet.” (Indian Conception of Values, p. 445).

Conclusion

Prof. Hiriyanna was never a blind adherent of tradition. What he wrote of the Indian civilization is also true of him: “… when a new stage of progress is reached, the old is not discarded but is consciously incorporated in the new. It is this critical conservatism which marks Indian civilization, as a whole, that explains its stability and constitutes its special strength.” (Popular Essays in Indian Philosophy, pp. 108–9). He also had some revolutionary ideas, such as for instance, his suggestion to replace religion with art, in accordance with the context of the modern world. He posited that “poetry, as criticism of life, is nearer to philosophy than science or religion.” (The Mission of Philosophy, p. 13). According to him, to mix art and religion is only to make the latter attractive. However, such endeavours have rescued art from hopeless degeneration.

Sanskrit texts related to Aesthetics are full of definitions and hair-splitting arguments about classifications and sub-classifications. So much so that Dr. S K De, himself a doyen of the subject, famously remarked, “It is like reading a catalogue than reading the actual text.” So a student wishing to study Alaṅkāra-śāstra in the original sources will do well to first study Hiriyanna’s works. This way his study will have a proper direction and he will not be overwhelmed by the multitude of information. On the other hand, if a scholar who has thoroughly studied the primary texts reads Hiriyanna’s works, he will surely be wonderstruck by the professor’s clarity of thought, felicity of expression, and his unsleeping insight that binds these two together. If we are to mark out the characteristics of studying Hiriyanna, it would be: vaiśadya (clarity) that greets us at the beginning, and a certain vismaya (wonder) that meets us at the end.

Lastly, Prof. Hiriyanna was both the inspiration for and the guiding force behind the work Bhāratīya-kāvyamīmāṃse written by his pupil Prof. T N Shrikantaiah (popularly known as Tī-naṃ-śrī). Written in exquisite prose, this work is a classic of modern Kannada. Prof. Shrikantaiah sat at the feet of his Guru and took lessons on Dhvanyāloka to muster the confidence required to write an analytical history of Indian Poetics. As Kannadigas, as lovers of literature, and as ardent advocates of Indian Aesthetics whose appeal is universal, we must remember Prof. M. Hiriyanna with respectful gratitude and loving reverence.

Almost eight decades have passed since the passing of Prof. Hiriyanna. However, as far as the theory of Indian Aesthetics is concerned, nothing has qualitatively changed in these years. This surely speaks volumes of the professor’s farsightedness.

“सतां प्राज्ञोन्मेषः पुनरयमसीमा विजयते”

“Limitless is a wise man’s flash of insight”

[Passages from Prof. Hiriyanna’s writings have been cited from the books published as part of The Mysore Hiriyanna Library. Bengaluru: Prekshaa Pratishtana, 2018]

[1] Prof. Hiriyanna wrote the first-ever thesis on Dhvanyāloka as part of his M.A., soon after its publication in 1890. However, since the text itself was very corrupt, he never published his work.

[2] Knight, William. The Philosophy of the Beautiful. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1891. p. 17

[3] In relation to this, it is important to note that Indian tradition recognizes their similarity in spirit. There are many poetic hymns in the Vedas (such as the Uṣas-sūkta), and the works of great poets are full of passages that echo the Vedic ethos.

[4] In writing a piece of poetry, a poet might have in his mind many ends such as fame, wealth, and happiness. A connoisseur, however, can only derive enjoyment by reading poetry; he cannot benefit in any other way. This is another point of difference between beauty in nature and that in art.

[5] Prof. Hiriyanna masterfully expounded on rasa (aesthetic experience), dhvani (suggestion), and aucitya (appropriateness), which are the fundamental tenets of Aesthetics. However, he did not lay adequate emphasis on vakrokti (indirect or oblique expression). While it may be argued that all forms of indirect expression are covered under dhvani itself, the fact of the matter remains that it is connoisseur-centric, while vakrokti is poet-centric. The centrality of a poet in the aesthetic process is uncontestable; therefore, turning a blind eye to it counts as a shortcoming. The reason for Prof. Hiriyanna not emphasizing vakrokti is rooted in his attitude that preferred nivṛtti (contemplative detachment) to pravṛtti (creative engagement).

Added to this was the off-putting cornucopia of over-ornamented works produced after the Classical Age in Sanskrit. This naturally led people with refined sensibilities toward poetic models that are less gaudy. While this is understandable, it had unfortunate, long-lasting repercussions: Prof. Hiriyanna’s students, who later became torchbearers of the subject themselves, also ignored vakrokti. We see a signal illustration of this trend in Prof. Prof. T N Shrikantaiah labelling the rasa-dhvani-vakrokti triad as ‘kāvya-gāyatri.’ As a result, beauty in expression became abhorrent to both poets and literary critics in Karnataka. With tools such as figures of speech that enable a poet to come up with delightful turns of phrases swept aside unceremoniously, riddles masquerading as poetry ruled the game. The atmosphere is largely the same today.

Dr K. Krishnamoorthy, who although belonged to the same school of thought as Prof. Hiriyanna, differed from this constructively and argued to do away with baldness in poetry. In our time, Śatāvadhāni Dr R. Ganesh has been a vocal, objective advocate of vakrokti.