DVG – These three letters evoke an image of a wise old man laughing a toothless laugh in the minds of the Kannada-speaking people. We are so accustomed to this image that any reference to a youthful DVG sounds and seems odd. We are startled by discovering that the author of Maṅkutimmana Kagga—a collection of verses capturing meditations on life in a “semi-philosophical vein”—wrote in English, mostly on such topics that resolutely maintain their distance from philosophy as law, politics, journalism, and economics.

DVG wrote more in English than he did in Kannada. A reliable estimate places the corpus of his English writings at fifteen thousand pages, which is more than twice the size of his complete works in Kannada. A good portion of this staggering body of literature first appeared either in the columns of one of the many newspapers and journals DVG himself edited and published, or in the tracts he wrote as responses to the then-current issues of public life. These journals and tracts were not complied or republished. Unsurprisingly, DVG’s English writings soon became inaccessible.

This is perhaps why DVG remains largely unknown outside of Karnataka.

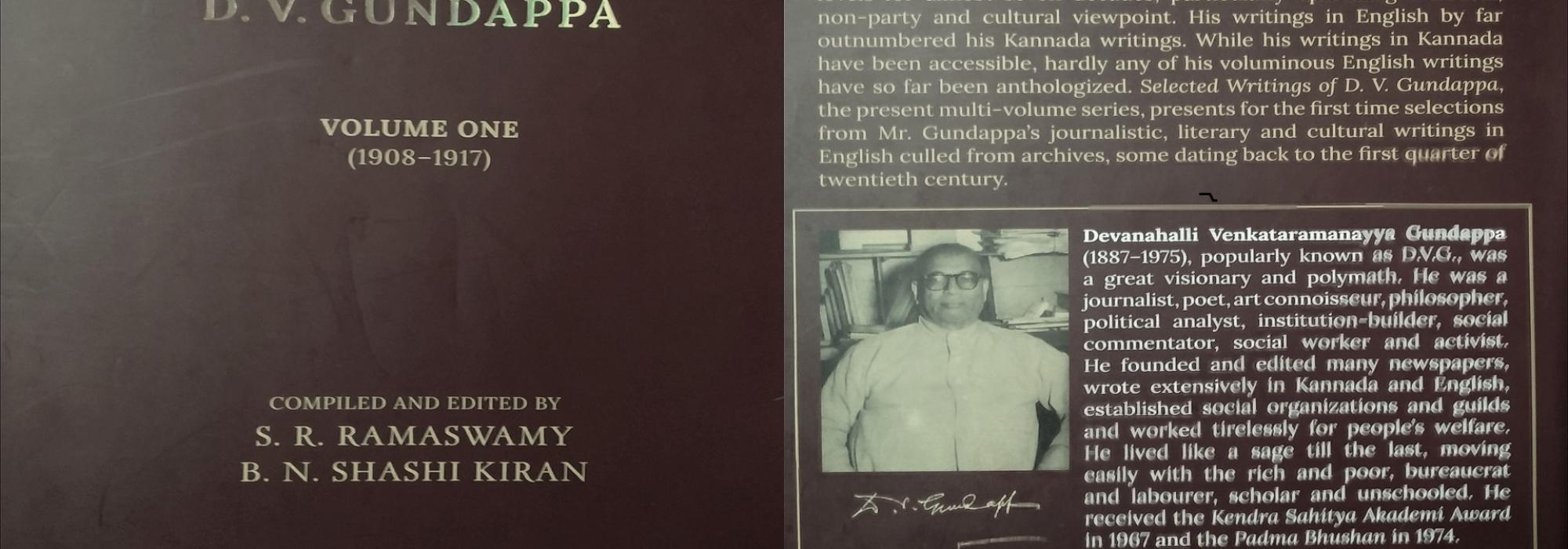

To remedy this, the Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs recently began to anthologize a few of his English works. Four volumes have been published so far, titled Selected Writings of D V Gundappa.[1] They cover a period of roughly forty years – from the time DVG entered journalism till the last phase in which India marched towards attaining independence.

In this article I intend to introduce the salient features of some of these writings. In the process, I hope to cast a searchlight on the mind of the man who was the conscience-keeper of the public life and literature of his time.

* * *

DVG had attained mastery over English, Kannada, and Sanskrit at a young age. He was intimately familiar with classical literature—creative and analytical, Indian and Western—before he began his career as a journalist. Armed with this equipment, he could:

- cultivate a distinctive literary style,

- guard himself against capriciousness, the foster child of journalism, and

- develop a worldview in consonance with the ultimate reality of things.

His entry into public life fortuitously coincided with the resurgence of national pride, the direct outcome of the Swadeshi movement.

The highest use of literature, to him, was “a certain grace and serenity.” He sought to harmonize politics and philosophy all through his life. He firmly believed that

Philosophy and politics are … two aspects of the same activity – pursuit of the good … The statesman concretizes and fulfils what the philosopher initiates and commends. Between them, they complete the service of the social good. Philosophy without the instrumentality of statesmanship is ineffectual longing and vain fancy-play. Politics without the inspiration of philosophy is a welter of blind forces and a raffle for the adventurous. (On Plato, unpublished)

* * *

Volume One (1908–1917)

The prologue and epilogue of DVG’s journalistic story share a section on his fearless, hard-hitting protest against governmental regulations that curb public freedom.

In 1908, he wrote a series of articles titled The Press Gag in Mysore, condemning Dewan V P Madhava Rao’s draconian legislation that intended to give short shrift to newspapers. The law of the time had the power to inflict capital punishment on DVG. But the twenty-one-year-old boy stood his ground. He went to Madras and published these fact-based articles in leading newspapers such as The Hindu, The Indian Patriot, and The Tribune. His reasoning was straightforward:

The Press is the most potent influence in these days; it is at once an instrument of progress and a means of self-protection. To destroy it is to destroy the freedom of the people and to impair their moral stamina. (p. 7)

The seeds of fierce independence, infallible logic, and vociferous expression had begun to sprout.

In the 1970s, well into the evening of his life, he demonstrated the same qualities with greater vigour. When the Emergency was declared, he quoted two sentences from the Rāmāyaṇa in the editorial of his journal, Public Affairs. Encased within a solid black frame, these words expressed his protest with exceptional force:

Vākyajño vākyakovidaḥ; tato maunam upāgamat |

The one well-versed in speech sought refuge in silence.

He delivered three lectures under the auspices of The Chennai Jana Sangham in 1909. The topic was Vedanta and Nationalism. Clearly, the unmellowed bloom of post-adolescence years was no barrier to DVG in submitting himself to the loftier aspects of life. Seen in the fresh backdrop of his journalistic endeavour, these talks effectively delinked him from the image of an angry young man and presented his true, well-rounded personality before discerning eyes.

The influence of Vidyāraṇya, Vivekananda, and Gokhale is clearly visible, because DVG stresses the importance of ‘spiritualizing public life’ and avers that unpolluted self-love is the true basis of ethics (p. 37). His worldview, by then, was inflexibly set:

Material interests unite beings at first and breed their attachment towards one another, entailing a certain amount of self-denial on the part of each individual and thereby surely paving the way for the expansion of the real Self … Just like the ripples which are produced when a little stone is plunged into water and which go on forming wider and wider circles till at last they have traversed the whole surface of the lake, when man becomes attached to something, his heart begins to be widened and it goes on embracing larger and larger areas till he continues to increase the number of those to whom he is attached. (p. 35)

He later captured this idea in a pregnant phrase—taraṅga-valaya-vistāra—in a book embodying his considered views on life, which he intended as a statement of faith for the common man.

Not only did he present his thoughts on the subject with a great amount of depth and detail, he also exposed the unsoundness of some of the views of no less an eminence than Herbert Spencer. Defending our culture against unjust allegations, he remarked:

He [Spencer] has said that we have always submitted ourselves to the pitiless tyranny of rulers. If this is said of our attitude after the advent of aliens on our shores, I have not much to say against it, except that wherever there was a Hindu sovereign, there was no tyranny. In days of yore, when the real descendants of the Kshatriyas ruled over the land there was absolutely no despotism, the Sanskrit word for Government, Rajya, having the germs of democracy in it. Says the Mahabharata, “Kingship or Government derives its authority by the pleasure and welfare of the people.” (p. 57)

Mildness or want of valour or even timidity or slavish cowardice is said to be the weakness of the Hindu. The names of Prahlada and Draupadi do not jump up to our lips when we think of passive resistance. (p. 65)

Incidentally, the last public talk he was supposed to deliver (1975) was also on Vedanta. It was titled Advaita: Faith and Practice. He dictated the lecture and had the manuscript ready before he passed away. The weltanschauung he had come to develop in his early twenties ripened over the decades. In the last lecture, he elucidated the practicability of the statement of faith he had previously espoused.

DVG wrote a short biography of Dewan C Rangacharlu in 1912. The Dewan advocated Responsible Government in a Princely State much before the idea became popular and started a Representative Assembly of citizens in Mysore, which was perhaps the first of its kind in our country. DVG was drawn to Rangacharlu’s foresight, sterling character, commitment, and administrative acumen. Contextualizing the Dewan’s work, he wrote, “His ideas of popular rights were shared by none of his contemporaries … It was some three years after his death that the Indian National Congress met for the first time.” (p. 93)

Eminent publicists took note of the biography. M Visvesvaraya, who was at the time scouring the state for well-informed people who could help him steer the political affairs of Mysore better, found his man in DVG. The biography includes the transcripts of two important lectures Rangacharlu delivered at the Representative Assembly. These documents of immense historical importance are not easily available elsewhere.

DVG’s biographical longform on Tolstoy (1917) was perhaps occasioned by the great novelist’s demise. It draws from his parables profusely and focuses on his moral and spiritual outlook. DVG does not sacrifice objectivity at the altar of reverence. Sample his summary assessment:

Viewed from the standpoint of either variety and richness, or devotion to a lofty and generous ideal, or influence exercised over contemporary mind and morals, the life of Tolstoy is — as it certainly was in sheer length (1828–1910) — a great one. It is remarkable alike for its relentless consistencies and its amiable inconsistencies, for its multifarious experiences and its essential unity, for its achievements and its experiments. (p. 141)

Tolstoy might appear as a ‘bundle of contradictions’ at first glance. Urging us to look deeper, DVG writes in a tone of reproachful persuasion:

The aspiring, failing, yet aspiring, and persevering life of such a man has obviously greater encouragement and greater hope to afford to common erring mortals than the monotonous flow of effortless virtue emanating from a born saint. (p. 163)

[1] Unless otherwise stated, all references in this article are to this series: Selected Writings of D V Gundappa (Ed. Ramaswamy, S R and Shashi Kiran, B N). Bengaluru: Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, 2019, 2020.

The present review is limited to this series. It does not include the entire corpus of DVG’s English works.

Nāḍoja S R Ramaswamy introduced me to the nuances of editing and provided incredible insights into the personality and works of D V Gundappa. Śatāvadhānī R Ganesh breathes life into all my activities. Sandeep Balakrishna patiently polished my prose and offered valuable suggestions to shore up the observations in this essay. I owe an immense debt of gratitude to all of them.

To be continued.