This is the second part of the two-part article published on the occasion of the 2018 Tyāgarāja Ārādhana Utsavam, which falls on today's date. — Editors

Bhakti

From his compositions, it is clear that Tyāgarāja suffered a lot. He remained poor throughout his life. More than that, he was tormented by people who did not understand or empathise with his spiritual yearnings. In his celebrated Kumārasambhavam, Kālidāsa says, “Alokasāmānyamacintyahetukaṃ dviṣanti mandāścaritaṃ mahātmanām” (Foolish people loathe the extraordinary behaviour of great souls, the reason for which is beyond their comprehension). Empathy for physical suffering and material destitution is easy to find, but it’s not possible to find the same for spiritual suffering. Tyāgarāja expresses this helplessness of his in a multitude of kṛtis.

In the Kāpi kṛti Anyāyamu sēyakurā, he says, “Nā pūrvaju bādha dīrpa lenani anyāyamu seyaku rā,” imploring Rāma to protect him from his elder brother. The story goes that his elder brother stole the vigraha of Rāma—the object of Tyāgarāja’s worship—and threw it into the river Kaveri. Out of that anguish, Tyāgarāja composed many beautiful kṛtis begging Rāma to come back to him. Finally, it is said that he found his Rāma when he went to bathe in the river. While such were the external tortures that he underwent, his mental tribulations were those of a man of the world yearning for the lotus feet of his iṣṭa-daiva. In various nindā-stutis, he scolds Rāma for neglecting him. In his Aṭhāṇa kṛti Aṭṭa balukuduvu, he says, “Toṭṭlanarbhakulanūtuvu, mari mari tocinaṭṭu gilluduvu” – You rock babies in the cradle and then pinch them as you like. In a Śaṅkarābharaṇa kṛti, he says “Eduṭa nilacite nīdu sommulemi bovura” – If you come and stand in front of me, will you lose your jewels? Through his nindā-stutis, he makes Rāma as intimate to us as he was to him.

At other times, in spite of his bhakti, he often admonishes himself as being unworthy of Rāma’s grace. This feeling is expressed beautifully in many of his kṛtis, the foremost being Duḍukugala, one of the five gems among his compositions. In this kṛti, he says “Mānava-tanu durlabhamunacunenci pāmanandamondalēka mada-matsara-kāma-lobha-mohulaku dāsuḍai mosapoti gāka” – Without realizing that the human body is difficult to attain, without attaining supreme bliss, I became the servant of pride, envy, lust, and greed and deceived myself. One cannot help thinking that if someone like Tyāgarāja thought of himself as a lost soul running behind worldly pleasures, what would he say to us, swimming in the ocean of saṃsāra without any respite!

In other kṛtis, he praises himself as a bhāgavata who is a friend of Rāma— “Rājaśikhāmaṇiyaina tyāgarājuni sakhuni maravarādu”—and sometimes calls himself “Vara-tyāgarāja.” He is enraptured by the sight of bhāgavatas – “Hariguṇamaṇimaya saramulu gaḻamuna śobhillu bhaktakoṭulu” but he always condemns mere show of bhakti. In the Kharaharapriya kṛti Naḍaci naḍaci, he says, “Aṭṭe kannulugūrci teraci sūtramubaṭṭi velaki-veṣadhārulai” – Closing and opening their eyes, they (the show-offs) turn the rosary in their hands. They travel a lot but they never reach Ayodhya (the abode of Rāma).

Tyāgarāja, the Haridāsa, was also a Vedānti. Indeed, we see in him a wonderful mix of the philosopher and the devotee, with each quality complementing the other. The famous Advaitic poet-philosopher, Madhusūdana Sarasvatī once said, “Advaita-vīthī-pathikairupāsyāḥ svānanda-simhāsana-labdhadīkṣāḥ / Haṭhena kenāpi vayaṃ śaṭhena dāsīkṛtā gopavadhū-viṭena.” (We[1] are worshipped by the travellers on the path of Advaita and seated on the throne of bliss of the Self. However, the cheat, the lover of the Gopis, has made us his slave). Likewise, though Tyāgarāja the philosopher said, “Tanalone dhyāninci tanmayame-gāvlalerā” (One should think about It and become It), his mind was enchanted by the charm of Rāma’s form.

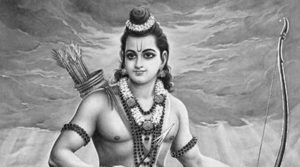

Tyāgarāja was never tired of describing the beauty, majesty and glory of Rāma. In his view, Rāma not only gives liberation to the soul, but also provides bliss to the senses by his beautiful form and his sweet speech. In his Sūryakāntam kṛti he says, “Muddumomu elāgu celangeno munuleṭla gani mohinciro” – How bewitchingly beautiful was Rāma’s face that even ascetics were enchanted by it. In Meru-samāna, he says that he wants to see “Nīrada kāntini … ālakala muddunu tilakapu tīrunu” – Rāma’s dark-hued lustre, the allure of his curls and the loveliness of his tilaka. His delightful speech is as sweet as sugar candy – “Paluku kaṇḍa cekkara.” In his Endu kaugaḻinturā, he says, “Nīdu paluke palukurā nīdu kuluke kulukurā” – Your speech alone is speech, your grace alone is grace. We see in him all the nine forms of devotion (nava-vidha bhakti[2]).

Musical Brilliance

Dwelling Amongst the Unsung Rāgas

Tyāgarāja is believed to have composed twenty-four thousand kṛtis. While we can choose to disbelieve it, certainly it gives us an idea of the aura that surrounded him. About seven hundred of his compositions are available now. In addition to ancient rāgas like Saurāśtra and Mukhāri, he also popularized rāgas like Kharaharapriya. Rāgas like Nārayani and Jayantasena were fruits of his immense creativity. He also brought into vogue rare rāgas that later became extremely popular, like Malayamāruta, Āndolikā, and Kalyāṇavasanta. Some of the Rāgaṅga rāgas that he popularized are Kharaharapriya, Cārukeśi, Vāgadhīśvari, and Kīravāṇi. The fact that these rāgas, which were unsung and only present in musicological texts, became full-bodied and capable of being expounded as manodharma pieces, speaks volumes about Tyāgarāja as an aesthetician. For instance, even though Kīravāṇi is a sampūrṇa rāga, the sañcāra with the usage of minimal Madhyama in the avarohaṇa is enchanting. This is undoubtedly the touch of Tyāgarāja, as presented in Kaligiyuṇṭe kada. This sañcāra gives Kīravāṇi a certain characteristic beauty. Similarly the kampita gamakas of Gāndhāra and Niṣāda in Kharaharapriya are also characteristic of that rāga.

Tyāgarāja composed multiple kṛtis in rāgas that give ample scope for improvisation, like Madhyamāvati, Kāmbodhi, and Mohana. Though composed in the same rāga, they differ greatly from one another; there is incredible variety in the tune. For instance, in Mohana, he has composed Mōhanarāma, Evarurā, Daya rāni, Bhavanuta, and so on. Even if these kṛtis are sung one after another, we do not find the music repetitive; this shows his genius.

There are, of course, some rāgas like Jiṅgala and Candrajyothi that have a limited range. And there are rāgas like Nādacintāmaṇi and Garuḍadhvani that cannot be improvised differently and his compositions are the only references we have. His compositions in these rāgas are so full of bhāva and so pleasing to the ear that these single, short kṛtis have become highly popular. The composers who came after him used these rāgas exactly as he did.

Tyāgarāja appears to have followed a different path from that of Muttusvāmi Dīkṣitar when it comes to handling some of the older rāgas, like Ānandabhairavi and Śrī. While we have the Sangīta Sampradāya Pradarśinī as an authentically preserved and maintained record of Muttusvāmi Dīkṣitar’s works, Tyāgarāja has no such luxury. We have to rely on the three schools (Walajpet, Thillaisthanam, and Umayalapuram) of Tyāgarāja’s disciples. While this dents our knowledge of exactly how Tyāgarāja had sung his compositions, it certainly does not interfere with our understanding and enjoyment and appreciation of them, and that is more important.

Contribution to Extempore Singing

Tyāgarāja was responsible for one more game-changing improvement in the field of Carnatic music – introducing the concept of saṅgatis. It might or might not be true, but Tyāgarāja certainly has used them extensively to bring out both lyrical and musical beauty in his compositions. Not only that, it is easy to find places suitable for neraval in his kṛtis. There are only a handful of kṛtis where the lyrics and the tune are unsuited for exposition (Teliyaleru Rāma, for example). Generally, he presents an idea in the Pallavi and explains them in the subsequent Anupallavi and Caraṇa. This method of presentation results in some really insightful sentences in the Anupallavi and Caraṇa, which can be expounded beautifully because of their musical quality as well. While there are several examples, to list a few may here may not be out of place – “Tanuvu ce vandana monarincucunnāra” in Pakkala nilabaḍi, “Kaṇṭiki sundarataramagu rūpame” in Cakkani rājamārgamu, “Mamatābandhanayuta narastuti sukhamā?” in Nidhi cāla sukhamā, “Tāmarasadala netri tyāgarājuni mitri” in Amma rāvamma. All of these lend themselves to exquisite musical elaboration.

The other fact that stands out is that he has used simple tāḻas everywhere. A majority of the kṛtis are in Ādi and Rūpaka tāḻas in Caturaśra naḍai; a few are in Miśra chāpu and Khaṇḍa chāpu. He doesn’t use complicated tāḻas like Dhruva, Maṭhya, or Jhampe. This gives the musician freedom to explore the rāga in detail, without being constrained by complicated tāḻas. He has composed a few kṛtis in vilamba kāla (slow tempo), but the laya of his choice is madhya-laya (medium tempo; also called madhyama kāla). This has made his compositions a staple food for musicians. It also gives percussionists abundant scope to perform aesthetic experiments with laya.

Legacy

Tyāgarāja was born at a time when Carnatic music was in a flux. While there was still some musical give and take between North and South India, Carnatic music had largely stabilized and had an identity of its own, quite distinct from Hindustani music. Purandaradāsa and the other musicians belonging to the Haridāsa community were already using music as a powerful tool to preach the path of bhakti to the masses.

Being a haridāsa himself, Tyāgarāja carried forward this legacy of haridāsas and composed musical poetry that had bhakti as its mainstay. While the haridāsa literature was greatly enriched by his poetry, it was the field of Carnatic music, especially concert music that saw the greatest change. He, along with the other composers of his time, paved the way for compositions of a particular style to become the main form of compositions presented in concerts.

Tyāgarāja influenced other musicians like Patnam Subramanya Iyer, Papanasam Sivan, and Mysore Vasudevacharya in their style of composition. Patnam particularly imbibed Tyāgarāja’s style so much that sometimes we get confused between his compositions and Tyāgarāja’s. Even modern composers adhere to his style – to propose an idea in the Pallavi and develop it in the Anupallavi and one or more Caraṇas.

Some of the rāgas that he popularized—Harikāmbodhi, Kharaharapriya, Haṃsanāda—went on to become so famous that Carnatic music cannot be imagined without them. Some of them are heard extensively on the concert-stage, with lots of embellishments and ornamentation in the compositions and manodharma. Of special mention are the renditions of Tyāgarāja kṛtis by Dr. M Balamuralikrishna. The face of Carnatic music was changed forever, and for the better.

There is a saying in Kannada, “ಶರಣರ ಜೀವನವನ್ನು ಮರಣದಲ್ಲಿ ಕಾಣು.” At a ripe old age, Rāma beckoned to Tyāgarāja from a hill and told him that he would attain sāyujya in five days. Tyāgarāja details this experience in his Sahana kṛti, Giripai nelakonna. Accordingly, Rāma took him to His abode on the fifth day after the full moon in the Puṣya month. To mark this occasion, thousands of musicians congregate at his samādhi and sing his kṛtis in praise of the Rāma he loved as his own – this is the famed Tyāgarāja Ārādhana.

At once a poet, philosopher, a creative musical genius, a composer and a performer beyond compare, any lesser mortal would have disappeared from the sky of Time like a flash of lightning. But because he made all of his talents subservient to his one ideal—Śrī Rāma—Tyāgarāja remains the pole star of Carnatic music. It is but fitting to conclude this short piece about him where I have tried to capture a huge elephant within a tiny photograph, with a line from his magnificent kṛti where his creative genius burnished with his humility is expressed: “Endaro mahānubhāvulu andariki vandanamulu.”

Thanks to Dr. T S Sathyavathi and Śatāvadhāni Dr. R Ganesh for their careful review and astute feedback. Edited by Hari Ravikumar.

Footnotes

[1] Here, the ‘we’ is used in the sense of ‘I’ – the Royal ‘I.’

[2] Nava-vidha bhakti refers to the nine forms of devotion outlined in the Viṣṇu-purāṇa and the Bhāgavata-purāṇa, viz. śravaṇa (listening to the glory of the Supreme), kīrtana (singing His names), smaraṇa (thinking of Him), pādasevana (serving at His feet), arcana (worship), vandana (bowing to Him), dāsya (service), sakhya (friendship), and ātmanivedana (offering oneself).

References

Raghavan V. Spiritual Heritage of Tyāgarāja. Chennai: Ramakrishna Math, 1999

Sathyavathi, T. S. Musical Excellence in the Compositions of Saint Tyāgarāja (video)

Thyagaraja Vaibhavam (website)

Sharma, Rallapalli Ananthakrishna. Gānakale. Bangalore: Karnataka Sahitya Academy, 2006

Krishnamurthy, S. Saṅgīta Saritā. Mysore: D V K Murthy, 2002

Shiji Rajan, K. V. Rare and New Ragas Handled by Tyagaraja.