This article is based on Ramaa Bharadvaj’s illustrative talk on June 18, 2017 at the workshop on Vyāsa, Vālmīki, Kālidāsa, and Guṇāḍhya at Chinmaya International Foundation, Veliyanad, Kerala.

It is presented in two parts for Prekshaa readers.

Preamble

It was 1992, and an amusing situation involving my 3-year old son acted as the catalyst, that led me to think about my role as a diaspora artist, and about the relevance of recreating my inherited artistic traditions. Thus, was born my dance-theater production “Pañcatantra-Animal Fables of India”. Through this nostalgic revisit, I share the thematic and aesthetic processes that went into choreographically translating tradition for global audiences.

In part-1 of this essay, I have explained about how I found that I could embrace Pañcatantra’s allegorical structure for raising philosophic questions about human perception of “Nature” and global ecology in today’s world. In part-2, I share how I navigated the production’s choreographic landscape.

Traversing the Choreographic Landscape

Movement motivators

I selected one representative story from each of the five Tantras, and commissioned original lyrics for them in five languages – Telugu, Tamil, Hindi, Gujarati and Marathi. This use of multiple languages greatly influenced the aesthetic flow, through choices in the style of music, costuming, and movement possibilities. Then, I worked with composer Rajkumar Bharathi for nearly a year to give musical life to the stories.

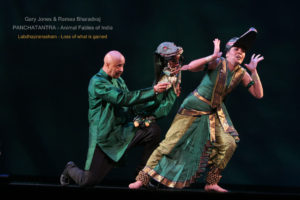

Although movement vocabulary drawn from Bharatanatyam and Kucipudi formed the choreographic base, several freestyle movements emerged as a result of inspiration derived from Nature herself, and from the animals that inhabit her kingdom (specifically in the episodes relating to monkeys and birds). For this, I watched nearly twenty hours of ‘National Geographic’ videos of animals in motion, and my dancers and I visited monkeys in the zoo, ran alongside bullock carts in Chennai, and sneaked behind crows on the terrace of my parents’ home, to study the body language of these creatures. Although this was going to be an empirical translation based on observation, the characters were to be portrayed not as realistic four-legged or winged creatures, but in a humanized form, as in the cartoons. In other words, we were not humans acting like animals, but animals acting like humans.

It was important that we did not settle into the comfort zone of facial expressions to express the moods. We had to emote with our entire bodies, because, after all, we were animals. So, I created partial and even full masks that made the body the primary tool of communication.

The early inspiration of ecological intention for the story also guided my costuming decisions. Only natural components such as strips of recycled paper, cotton cloth, flour, coconut fiber, and feathers went into the hand-making of the animal masks. I also made a conscious decision of not using silk as a material choice for costumes because a single silk saree harbored a violent end for thousands of silk-worms.

The Artist-Rasika kinship

The guiding principle in my choreographic process was the creation of fantasy. Our audiences were not to remain as witness to the stories but were to become emotional participants. So, even as they entered the theater, they were greeted by forest sounds and hand carved signs, warning against feeding or petting the animals.

Having taken them into a make-believe world, we had to help them stay there for the length of the performance. So, in our animal roles, we kept things as real as possible. If the monkey had to stop and scratch his butt or snatch a tick off his friend’s head, he simply had to do it; if the lion had to whisk a fly with his tail, or polish his claws he had to do it. As for when a fly would land, or an itch would occur, nobody knew, not even our dancers. These being humanized animals, their zany antics also included giving high-fives, batting eyelids, strutting their stuff, and such. To keep this riotous spontaneity alive, I structured the rehearsals like an improv-class, and dancers were encouraged to surprise each other with shenanigans, even on the performance stage, as long as they stayed in rhythm and formation. This heightened their level of alertness and wit required during the performance.

Illustrative Example

The opening story of Mitrabheda, about a lion-king, jackal and bull, had all the grandeur of a mythological tale complete with intrigue, deception, jealousy, and drama, along with a royal character as its protagonist. So, I chose Kucipudi, with its inherent flair for drama, for its portrayal. I share four examples of how I adapted the salient features of Kucipudi to my animal fables:

The opening

Use of humor was the most important foundation for my choreography. An example was the opening scene, similar to the Pagaṭi-veśam concept in Andhra which also used humor and characters such as komaṭi or merchant, as is portrayed here. This is also the scene where I make my grand appearance in an unrecognizable form.

Pātrapraveśa Daru (Character-entry song)

The introduction of the main character through descriptive song and movement is a traditional approach in Kucipudi dance-theater. I applied this concept during the entry of the Lion-king and his entourage. The accompanying song abundantly describes the glories of the royal hero. However, while the dance movements were important to introduce the Kucipudi style entrance, the antics of the animals were equally important in introducing the personality of each character.

Tail vs Braid

In Kucipudi, the ‘jaḍā’ or braid has great significance. In the Bhāma Kalāpam dance-drama, the heroine Satyabhāmā’s long braid is a legendary feature. In my adaptation, the tail of the lion, which is said to be the pride of an animal, took on a similar significance.

Tarangam - The “Plate” Dance

A Kucipudi scene would have been incomplete without the classic “plate dance”. But, a brass plate in a forest! So, I devised a ‘road-kill’ in the corner of the stage under a tree - an unfortunate traveler and his possessions, complete with skulls and bones. Among this booty lay the brass plate. The plate became major prop creating a play toy for the jackals, an object of fascination for the lion, and plenty of laughs for the spectators.

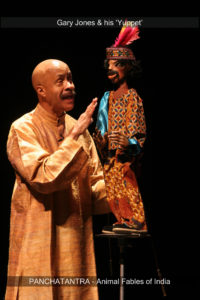

After my son grew up, I changed the story-narration scenes by starting a collaboration with the famed puppeteer, Gary Jones of the Blackstreet USA Puppet Theater. This artistic union lasted for over 10 years, adding tongue-in-cheek humor to the production. Together, we entertained thousands of children, while introducing them to India’s famed Fables depicted through India’s classical dance idioms.

Tribute to the Torchbearers

If the torch of our artistic heritage is to pass on through generations, we must interest our children and youth in our art forms. By treating them as our primary audience, we can truly initiate this connection and inspiration. Although the creation of my ‘Pañcatantra’ was an instinctively organic process, and I had no child-psychology strategy in mind, (for I am no expert on the subject), I have come to appreciate the remarkable qualities of children, through my numerous interactions with them during ‘Pañcatantra’s 15-year performance circuit. I share a few of my observations here.

Swami Chinmayananda said, “children are not vessels to be filled, but lamps to be lit.” However, we adults tend to ADULTerate them by filling them with our own ideas. In an un-Adult-erated state, children are …

1. Sharper than adults in their observational, cognitive, language learning abilities.

2. Imaginative! They believe a fantasy to be possible because they are filled with the capacity of wonderment. It is that extraordinary quality that Rumi recommended for adults through his mystic statement, “sell your cleverness, and buy bewilderment”.

3. Curious and Adventurous! They are ready to explore new ideas and adventures. While the adult mindset seeks 'Result' and considers an experience as wasted time unless it offers some physical, emotional or intellectual gain, children enjoy a moment or an experience simply because it is there.

4. Drawn to humor!

5. Spontaneous! They are unconditioned by any notion of what things “ought to be”. Therefore, if there is no spontaneity in our characterization, we will lose them instantaneously. We cannot ACT it, we have to BE it.

This awareness forever changed what, and how I create for children. I went on to receive commissions for children’s works which led me to create minor works such as “Parade of White elephants”, “Story of Light” and others. My creations, however, were not just for the ‘child’ in chronological age, but for all those willing to invoke the ‘child’ within them.

The Impact

The need for works created specifically for children, in the Indian classical dance genre (works that are secular, yet sublime in content) is evident from the fact that my ‘Pancatantra – Animal Fables of India’ remained continuously active in my repertoire for 15 years, (from 1994 to 2009, when I left the US to return to India) and has been seen by over 20,000 children. While grateful for the opportunities and acknowledgments, it is a charming personal testimony that I consider to be a true illustration of the success of my ‘Pancatantra’. It comes from my student Regina who played the role of Sanjivaka, the bull. She trained intensely for this, and other animal roles, for several months. After that experience, one day she announced that she had decided to become a vegetarian because, as she explained, “I can’t eat one of my own species anymore”! Interestingly, in the story, the bull (played by Regina), advises the lion to become a vegetarian. Here is that clip.

Conclusion

For a tradition to continue, new energy must constantly offer the nourishment of new experience and revelations. Only then does it become a living tradition. Living art forms are those engaged in re-imagining the inherited traditions for ourselves and for the global community in which we live. Such a reconstruction demands deep faith in the traditions that we draw our inspiration and techniques from.

It is not through a habitual linear reproduction, but from returning to the source and resurfacing with a mindful re-making, that truly original works emerge. Here, I do not ascribe the commonly understood meaning of “never-before-seen-newness” to the word “Original” (for after all there is nothing new under the sun). Instead, I use it in its etymological sense of returning to the origins and re-creating from it. Originality is really about linking ideas and experiences, and harmonizing them into a neo-avatar, just as Viṣṇuśarma himself did when faced with the daunting task of having to educate the princes of Mahilārūpya. As Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Archibald MacLeish said:

What humanity needs is not the creation of new worlds but the re-creation in terms of human comprehension of the world we have, and it is for this reason that arts go on from generation to generation.

Comments